Leen Helmink Antique Maps

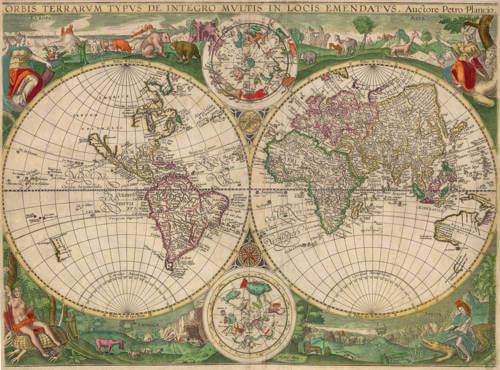

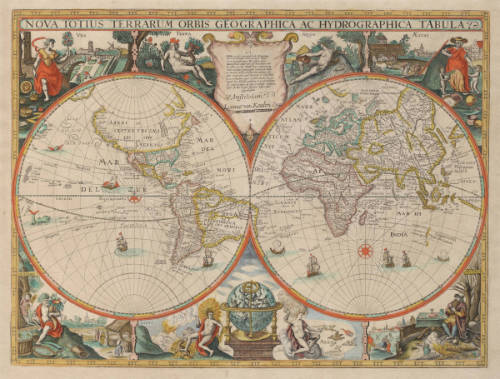

Antique map of the World by Petrus Plancius / Hugo Allard

The item below has been sold, but if you enter your email address we will notify you in case we have another example that is not yet listed or as soon as we receive another example.

Stock number: 19665

Zoom ImageTitle

Orbis Terrarum Typus De Integro Multis in Locis Emendatus

First Published

Amsterdam, 1595

Size

40.0 x 55.0 cms

Technique

Condition

pristine

Price

This Item is Sold

Description

ORBIS TERRARVM TYPVS DE INTEGRO MULTIS IN LOCIS EMENDATVS. Auctore Petro Plancio. Hugonis Allardi | excudit.

Copper engraving and etching; original colouring, 40 x 55 cm.

Only the second copy known

Hugo Allard’s world map of ca. 1650: A mile stone in the cartographical representation of Australia

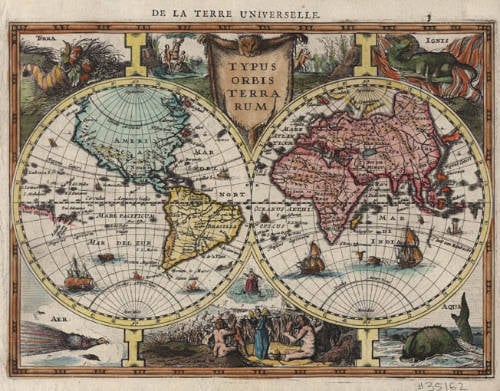

Petrus Plancius' famed world map in two hemispheres from 1594 (Shirley 187), distinguished by its contemporaneously good cartographical representation and its decorative appearance, served as a model for several world maps. Some appeared as separate folio maps on the market and belong today to major cartographic rariora. Certainly counted among these is the world map published by Paul de la Houve around 1600 in Paris, which subsequently, after the disclosure of Tasman’s results, was updated by Hugo Allard in Amsterdam around 1650.

The edition by De la Houve, ca. 1600

The Antwerp-born Paul van der Houve (Paul de la Houve; c. 1575- c. 1645) lived in Paris from around 1600, where he worked as a publisher and dealer of prints and maps. His cartographical work is not original, partly using purchased older copper plates, partly having copies made of existing maps. Among the second category belongs the copy of Plancius' world map from 1594. De la Houve explicitly mentions his name in the title of his world map. His own imprint stands right of the southern celestial hemisphere: Paules de la Houue excudit.

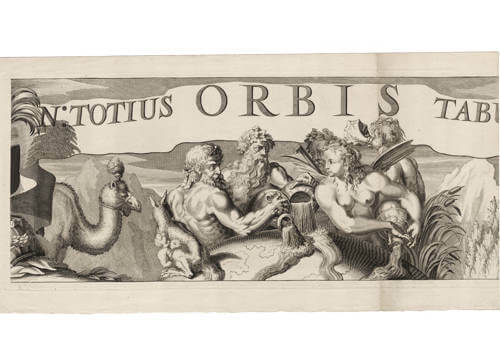

On his world map issued around 1600, however, De la Houve employed a compilation. While he took over Plancius’ map image, he copied the allegorical personifications of the continents from the world map by Joan Baptista Vrients (1596) (Shirley 192), which was also a derivative copy of Plancius’ map and engraved by the brothers Arnold and Henricus van Langren.

On De la Houve’s world map, the hemispheres are framed by allegorical personifications of the four continents. The upper space is occupied by Europe and Asia, while Africa and America are depicted below. Unlike the depiction on the Plancius map of 1594, a division of America into regions is omitted. The female figures are modifications of allegorical representations of the continents as presented in the print series by Adriaen Collaert after designs by Maerten de Vos. The main figures are placed in landscapes typical of their respective continents and hold characteristic attributes in their hands: the crowned Europe sits on a globe with a scepter and a cornucopia in her hands; Asia is seated on a camel, holding a censer in her right hand, while her left hand rests on the scabbard of a sword; the scantily clad Africa sits on a crocodile holding a bow and a sprig of spices; America, clothed only with a loincloth and adorned with feathers, sits on a giant armadillo armed with an arrow and a spear. The clothing and attributes of the women clearly demonstrate the intended hieratic structure of the four continents: after the richly clothed Europe and Asia follow the naked figures of Africa and America.

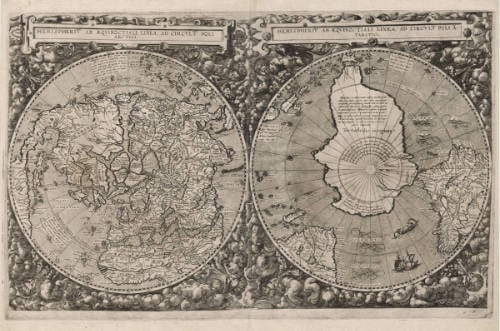

De la Houve’s map closely aligns with what Plancius provided in 1594. The depiction of East Asia showed progress in geographic knowledge, particularly regarding the southern coasts of Japan and the delineation of the Korean peninsula. The Philippines with Luzon are represented more correctly than previously. New Guinea forms part of the vast southern land named Magallanica, occupying a large portion of the southern hemisphere. In the Arctic region, four large polar islands are drawn, though legends indicate Plancius himself no longer believed in their existence. Novaya Zemlya is depicted as an island, and further west, several islands have broken off from this polar land.

The later state by Hugo Allard, ca. 1650

De la Houve’s copper plate was reused by Hugo Allard (died 1691), founder of the renowned Amsterdam family of publishers, map, and print dealers. No atlases by Hugo Allard himself are known; his oeuvre was limited to issuing individual maps, now quite rare. Three larger collections are known, in which maps by Hugo Allard were bound by collectors: the former Lord Wardington Collection (Sotheby’s **), the British Library collection, London (Shirley **[Atlases]), and the Osher Library (Maine). But none of the trio possesses Hugo Allard’s altered reissue of De la Houve’s world map. In his enumeration of significant cartographical documents for the history of Australian discovery, Schilder (1976, Map 72) lists the only known copy of the map in the Royal Library of Belgium in Brussels.

The world map must be counted among Hugo Allard’s earliest works. Koeman (1967-71) I, p. 31 suggested his cartographical activities began in 1645. However, the oldest documented cartographical work is already a reissue of Willem Jansz.' [Blaeu] folio map of Holland from 1604, republished by Hugo Allard in 1640 (Blonk 2000, Map **).

Only part of Allard’s inventory consisted of original material; throughout his career, Allard purchased inexpensive second-hand copper plates at auctions. When reissuing, Allard partly settled for adding his name as publisher, partly having copper plates reworked in his workshop to yield a seemingly new product.

On the world map issued around 1650, a combination was applied. The original impressum was changed to: Hugonis Allardi excudit. Allard left the highly decorative framing of the two hemispheres intact but introduced changes to the map image using Joan Blaeu’s large wall map of the world (1648).

Plancius' four large polar islands disappeared, replaced by Dutch discoveries in the northeast and English discoveries in the northwest. In North America, a fundamental change occurred: California is now depicted as an island. The entire east coast was re-engraved, considering the voyages of Hudson, Button, Bylot, and Baffin, and also the coasts of New England (Nova Anglia) and New Netherlands (Nova Belgium). In South America, map revisions were made based on voyages by Le Maire and Schouten (1616), the brothers De Nodal (1619), and L'Hermite and Schapenham on the so-called Nassau Fleet (1624).

But Hugo Allard’s world map is especially significant for depicting Dutch discoveries in Australia. The characteristic vast unknown southern land of the first state completely vanished, replaced by results of Tasman’s voyages and his predecessors: Australia (HOLLANDIA NOVA), Tasmania (Antoni van Diemens Landt), and New Zealand (ZEELANDIA NOVA). Hugo Allard’s world map is the oldest printed folio map incorporating Abel Jansz. Tasman's voyages of 1642/43 and 1644, forming a milestone in cartographic development of the fifth continent, named HOLLANDIA NOVA after Tasman’s journeys.

The following toponyms recall the voyages of Tasman:

2nd voyage of 1644:

HOLLANDIA NOVA

C. van Diemen

Tasmans Reuier

Vuyle bocht

Witte Water

Van Diemens Lant

1st voyage of 1642/43:

Antoni van Diemens Landt

West Eylanden

Boreels Eylanden

Tasmans Eyl

Van derlints Eyl

ZELANDIA NOVA

Clippige hoec

Moordenaers bay

C. P. Boreel

C. Maria van Diemen

T Ey[l] Drikonigen

Literature:

Wieder (1925-33) II, p. 39, Nr. 42 (state I); Koeman (1967-71) I, pp. 31-48 concerning the Allard family; Schilder (1976) Map 72 (state II), ill.; De Ramaix (1980) Nr. 86 (state I) and concerning De la Houve); Shirley (1983) Nr. 225 (state I) and Nr. 377 (state II), ill.; Schilder (2003) 10.3.1B (states I and II), ill.

F.C. Wieder, Monumenta Cartographica. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1925-33. 5 vols.

C. Koeman, Atlantes Neerlandici: Bibliography of terrestrial, maritime and celestial atlases and pilot books, published in the Netherlands up to 1880. Amsterdam: Theatrum Orbis Terrarum Ltd., 1967-71. 5 vols.

G. Schilder, Australia unveiled: The share of the Dutch navigators in the discovery of Australia. Amsterdam: Theatrum Orbis Terrarum Ltd., 1976.

I. de Ramaix, ‘Paul de la Houve. Contribution à sa vie et à son oeuvre d'éditeur’. In: Le Livre et l'Estampe 101-02 (1980) pp. 7-69; ‘Addenda. Errata’. In: Le Livre et l'Estampe 107-08 (1981) pp. 210-230.

R. W. Shirley, The Mapping of the World: Early printed world maps 1472-1700. London: The Holland Press, 1983.

G. Schilder, Cornelis Claesz (c. 1551-1609): Stimulator and Driving Force of Dutch Cartography. (= Monumenta Cartographica Neerlandica, Vol. VII). Alphen aan den Rijn: Canaletto, 2003.

Shirley >>>atlases in BL

Rarity

This map of the world is lacking in all collections. Thus far only known in one copy, in the royal library of Belgium in Brussels. The copy here is the second copy known.

Significance

This world map is of highest significance for the cartography of Australia, being one of the first maps to show the results of Abel Tasman's voyages, and the first map in folio format to do so.

Condition description

Strong and even impression of the copperplate. In attractive contemporary colour. No restorations or imperfections. A pristine example.

Petrus Plancius (1552-1622)

Born as Peter Platevoet in Flanders, Petrus Plancius studied abroad and became a theologian and a mapmaker.

He produced some globes and maps, including a well-known world map in 1592. He had a great influence on the Dutch Asian expeditions.

Early Years

Peter Platevoet was born in 1552 in the Flanders village of Dranouter. Little is known about his childhood, but it seems that his parents became Protestants. Platevoet studied theology, history, and languages in Germany and England. In England he probably learned about mathematics, astronomy, and geography. When he was older, Platevoet Latinized his name, as was the custom among savants at that time.

In 1576 he became a preacher in West-Flanders, a province in Belgium, and later that year he went to Mechelen, Brussels, and Louvain. In the 1580s he stayed in Brussels for a long time, but when the city surrendered to the duke of Parma, King Philip II of Spain’s governor-general in the Netherlands, in 1585 Petrus Plancius fled to the north. He lived in Amsterdam and became a pastor of the Dutch Reformed Church. From December 1585 until his death on 15 May 1622, he fulfilled his job as preacher. Plancius was a fervent Contra-Remonstrant and discussed many theological issues.

In addition to his thorough knowledge of the Holy Bible, he was well-grounded in the study of cosmography, geography, and cartography. He was not only one of the most talked-about preachers in the Dutch republic, but also one of the important mapmakers of his time.

Early Publications

Petrus Plancius was the first caert-snyder (map cutter) in the Dutch republic to produce waxed grid maps. Therefore, on 12 September 1594 he received a patent for the publication and distribution of the world map for twelve years from the States-General. He was, together with the Flemish engraver and map-maker Jodocus Hondius and the brothers Van Langren, one of the first makers of celestial globes in the Netherlands. His first globe was produced in 1589, a revision of an earlier celestial globe. Among his revisions were four additions to the southern sky: the two Magellanic Clouds (they were unnamed on the globe) and two new constellations, Crux and Triangulus Antarticus. Their positions were taken from reports of explorers.

In 1590 Petrus Plancius made five terrestrial maps for a Dutch edition of the Holy Bible. Two years later he made a well-known world map: Nova et exacta terrarum orbis tabula geographica ac hydrographica (New and exact geographical and hydrographical map of the world). This map contained celestial planispheres in the upper corners on which he added two additional constellations.

Asian Expeditions

Petrus Plancius was one of the driving forces behind the first Dutch expeditions to Asia, assisting with preparations and providing instruction. To avoid encounters with Spain and Portugal, which were already sailing to the East Indies around southern Africa, Plancius decided to try a northeast route around Asia. He supplied maps for the voyage and advised the fleet commander, Willem Barents, in celestial navigation. The northeast voyages of 1594 and 1595 were failures, but a third attempt was made in 1596. It was on that last expedition that Barents’s ship got stuck in the polar ice, and the crew had to spend the winter in Nova Zembla, an island northwest above Russia, in what came to be called the Barents Sea. Late in the spring of the next year, the crew was able to sail south in two small boats. Barents died on the return voyage; the survivors arrived at Amsterdam in November 1597, not having found a northeast passageway.

In 1595, together with Barents, Plancius published a book titled Nieuwe Beschrijvinghe ende Caertboeck van de Middelandtsche Zee (New description and map book of the Mediterranean Sea). In this work he designed a map that was engraved by the well-known globe- and map-maker Hondius.

Because the northeast sea route around Asia did not seem very promising, even before the third voyage a group of Dutch merchants had financed a southern expedition. Plancius again helped with the planning and used the opportunity to conduct scientific research. A theory in the late sixteenth century claimed that a compass needle’s variation from north (its declination) would enable one to determine longitude. Plancius developed his own theory to ascertain longitude at sea by means of magnetic variation. To test that theory during the southern voyage, Plancius taught junior merchant Frederik de Houtman how to measure and record compass declinations. It is known that the method developed by Plancius was used from 1596 onward by mariners.

Plancius also used the voyage to discover southern stars that were not visible from Europe. He taught navigators, especially Pieter Dircksz Keyser, but also other sailors, how to measure star positions with an astrolabe and instructed them to chart the southern sky. From ship records of 1596 it is known that the astrolabe was used to measure the declination of the southern stars.

The Dutch southern expedition, known as the Eerste Shipvaart, or First Voyage, set sail from the port of Texel in April 1595. It reached the East Indies in 1596 and returned to Texel in August 1597. Plancius asked Keyser, the chief pilot on the Hollandia, to make observations to fill in the blank area around the south celestial pole on European maps of the southern sky. Keyser died in Java the following year, but his catalog included 135 new stars arranged in twelve new constellations. Most of them were invented to honor discoveries by sixteenth-century explorers. They were first published on a 1598 celestial globe made by Hondius.

After the foundation of the VOC (Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, or East India Company) in 1602, Plancius became its first mapmaker. During the first quarter of the seventeenth century, he seemed more interested in preaching than in cartography and cosmography. But still, some of his maps were published during that time. In 1607 he produced a large revised world map. In 1612 he created a celestial globe, and later he designed an Earth and another celestial globe (1614 and 1615), both brought out by the well-known publisher Petrus Kaerius. His contemporaries described him as one of the greatest geographers of his time.

Bibliography

A complete bibliography of Plancius’s work, with descriptions of much of his maps and publications, is Günter Schilder, Monumenta Cartographica Neerlandica, Vol. VII, Cornelis Claesz (c. 1551–1609): Stimulator and Driving Force of Dutch Cartography, Alphen aan den Rijn, Netherlands: Canaletto/Repro-Holland, 2003.

(encyclopedia.com)

Hugo Allard the Elder (1627-1684/91)

Hugo (or Huygh) Allard the Elder (1627–1684 or 1691, not be be confused with his grandson of exactly the same name) was a notable figure in the Dutch Golden Age of cartography, a period renowned for its advancements in mapmaking and exploration. Born in 1627, likely in Tournai (modern-day Belgium), Allard emerged as a draughtsman, engraver, and painter before establishing himself as a mapmaker and publisher in Amsterdam, the thriving hub of the 17th-century Dutch printing trade. His career, spanning roughly from the 1640s to the 1680s, coincided with a time when the Netherlands dominated global cartography, rivaled only by the likes of the Blaeu family and the Hondius-Janssonius partnership. Though not as prolific or celebrated as these giants, Allard’s finely crafted maps earned him a respected place in this competitive field.

Allard’s entry into cartography began around 1645, when he set up his business in Amsterdam, a city teeming with intellectual and commercial energy. Operating from a shop "op den Dam" (on the Dam Square), he initially focused on reissuing existing maps, a common practice among smaller publishers of the era. These early works were often based on the output of predecessors like Willem Blaeu or Jodocus Hondius, reflecting the collaborative and iterative nature of Dutch mapmaking. However, Allard soon distinguished himself by producing original maps, albeit in limited quantities. His output, consisting primarily of loose, single-sheet maps rather than bound atlases, showcased his skill as an engraver. These maps were praised for their elegant design and meticulous detail, qualities that rivaled the best works of his contemporaries.

Active during the mid-17th century, Allard’s career peaked around 1650, a time when the Dutch Republic was at the height of its maritime and economic power. One of his most notable contributions from this period is the 1656 map of New England, "Totius Neobelgii Nova et Accuratissima Tabula," which depicted the Dutch and English colonies in North America. This map, derived from earlier works like those of Jan Janssonius, included a striking view of New Amsterdam (now New York) based on a drawing by Claes Jansz Visscher. The map’s blend of geographic precision and artistic flair exemplifies Allard’s ability to cater to both practical and aesthetic demands. Other works attributed to him include maps of Spain, Guinea, and the East Indies, reflecting the Dutch interest in global trade and exploration.

Unlike some of his peers, Allard did not produce large-scale atlases during his lifetime. His focus remained on individual maps, which were often sold separately or compiled into informal collections known as "atlas factice." This approach may have limited his fame compared to publishers like Joan Blaeu, whose grand Atlas Maior set a benchmark for the era. Nonetheless, Allard’s work was admired for its craftsmanship, with contemporaries like J.G. Gregorii later noting his skill, even if his maps prioritized beauty over cutting-edge scientific accuracy.

Allard’s personal life remains less documented, but he laid the foundation for a family legacy in cartography. Based in Amsterdam, he worked alongside his wife and raised a son, Carel, who would later inherit the business. The exact date of Hugo’s death is uncertain—some sources cite 1684, others 1691—marking a point of ambiguity in his story. Before his passing, he appears to have gradually handed over operations to Carel, who took over the shop by the early 1680s. Hugo’s death marked the end of his direct involvement, but his influence endured through his son’s continuation of the family trade.

Related Categories

Related Items