Leen Helmink Antique Maps

Old books, maps and prints by Hugo Allard the Elder

Hugo Allard the Elder (1627-1684/91)

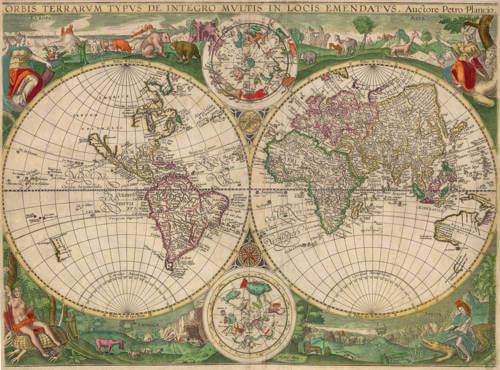

Hugo (or Huygh) Allard the Elder (1627–1684 or 1691, not be be confused with his grandson of exactly the same name) was a notable figure in the Dutch Golden Age of cartography, a period renowned for its advancements in mapmaking and exploration. Born in 1627, likely in Tournai (modern-day Belgium), Allard emerged as a draughtsman, engraver, and painter before establishing himself as a mapmaker and publisher in Amsterdam, the thriving hub of the 17th-century Dutch printing trade. His career, spanning roughly from the 1640s to the 1680s, coincided with a time when the Netherlands dominated global cartography, rivaled only by the likes of the Blaeu family and the Hondius-Janssonius partnership. Though not as prolific or celebrated as these giants, Allard’s finely crafted maps earned him a respected place in this competitive field.

Allard’s entry into cartography began around 1645, when he set up his business in Amsterdam, a city teeming with intellectual and commercial energy. Operating from a shop "op den Dam" (on the Dam Square), he initially focused on reissuing existing maps, a common practice among smaller publishers of the era. These early works were often based on the output of predecessors like Willem Blaeu or Jodocus Hondius, reflecting the collaborative and iterative nature of Dutch mapmaking. However, Allard soon distinguished himself by producing original maps, albeit in limited quantities. His output, consisting primarily of loose, single-sheet maps rather than bound atlases, showcased his skill as an engraver. These maps were praised for their elegant design and meticulous detail, qualities that rivaled the best works of his contemporaries.

Active during the mid-17th century, Allard’s career peaked around 1650, a time when the Dutch Republic was at the height of its maritime and economic power. One of his most notable contributions from this period is the 1656 map of New England, "Totius Neobelgii Nova et Accuratissima Tabula," which depicted the Dutch and English colonies in North America. This map, derived from earlier works like those of Jan Janssonius, included a striking view of New Amsterdam (now New York) based on a drawing by Claes Jansz Visscher. The map’s blend of geographic precision and artistic flair exemplifies Allard’s ability to cater to both practical and aesthetic demands. Other works attributed to him include maps of Spain, Guinea, and the East Indies, reflecting the Dutch interest in global trade and exploration.

Unlike some of his peers, Allard did not produce large-scale atlases during his lifetime. His focus remained on individual maps, which were often sold separately or compiled into informal collections known as "atlas factice." This approach may have limited his fame compared to publishers like Joan Blaeu, whose grand Atlas Maior set a benchmark for the era. Nonetheless, Allard’s work was admired for its craftsmanship, with contemporaries like J.G. Gregorii later noting his skill, even if his maps prioritized beauty over cutting-edge scientific accuracy.

Allard’s personal life remains less documented, but he laid the foundation for a family legacy in cartography. Based in Amsterdam, he worked alongside his wife and raised a son, Carel, who would later inherit the business. The exact date of Hugo’s death is uncertain—some sources cite 1684, others 1691—marking a point of ambiguity in his story. Before his passing, he appears to have gradually handed over operations to Carel, who took over the shop by the early 1680s. Hugo’s death marked the end of his direct involvement, but his influence endured through his son’s continuation of the family trade.