Leen Helmink Antique Maps

Old books, maps and prints by Homann Heirs

Johann Baptist Homann (1664-1724)

Johann Christoph Homann (son) (1703-1730)

Homann Heirs (1730-1852)

The Homann Family of Publishers: Pioneers of 18th-Century German Cartography

The Homann family stands out as one of the most significant map-making dynasties in 18th-century Germany, particularly in Nuremberg, where they established a formidable presence in the world of cartography. At the heart of this legacy was Johann Baptist Homann, born in 1664 in Oberkammlach, a small town in Bavaria. Initially trained for a career in the church at a Jesuit school, Homann's life took a profound turn when he converted to Protestantism in 1687, which led him to Nuremberg, where he would lay the foundations of his future enterprise.

Homann's journey into cartography was not immediate. After his conversion, he worked as a notary in Nuremberg but soon found his calling in engraving and map-making. His skills were honed in Vienna from 1693 to 1695, where he perfected the art of copper plate engraving. Returning to Nuremberg around 1698, Homann established his own publishing house in 1702, which would soon become a cornerstone in German cartography. His first major work, the "Neuer Atlas" published in 1707, marked the beginning of a prolific output that would see him rise in both reputation and influence.

In 1715, Homann was appointed Imperial Geographer by Emperor Charles VI, an honor that underscored his significance in the field. This appointment not only elevated his status but also provided him with imperial printing privileges, which protected his work from unauthorized replication. That same year, he was also admitted into the Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin, further cementing his scholarly credentials. His masterpiece, "Grosser Atlas über die ganze Welt" (Grand Atlas of all the World), published in 1716, showcased his mastery over both the art and science of map-making, featuring detailed and ornate maps that were both functional and aesthetically pleasing.

Upon Johann Baptist Homann's death in 1724, his son, Johann Christoph Homann, took over the business. However, Johann Christoph's tenure was short-lived as he passed away in 1730. The firm then transitioned into the hands of Homann's heirs under the name "Homann Erben" (Homann Heirs), managed by trusted associates Johann Michael Franz and Johann Georg Ebersberger. This continuity ensured that the legacy of high-quality map production continued well into the 19th century, with the company maintaining its reputation through the publication of atlases like the "Atlas Geographicus Maior" in 1780 and the "Atlas Homannianus" in Amsterdam from 1731 to 1796.

The Homann family's contribution to cartography was not just in the volume of their work but in their approach. They revolutionized map-making by focusing on both detail and accuracy, which was somewhat novel compared to the more decorative maps of their Dutch, French, and English contemporaries. Their maps were not only used for navigation but also for educational purposes, reflecting the Enlightenment's emphasis on knowledge dissemination. The collaboration between Johann Baptist Homann and Johann Gabriel Doppelmayr on celestial maps further diversified their portfolio into astronomy, producing works like the "Atlas Coelestis" in 1742.

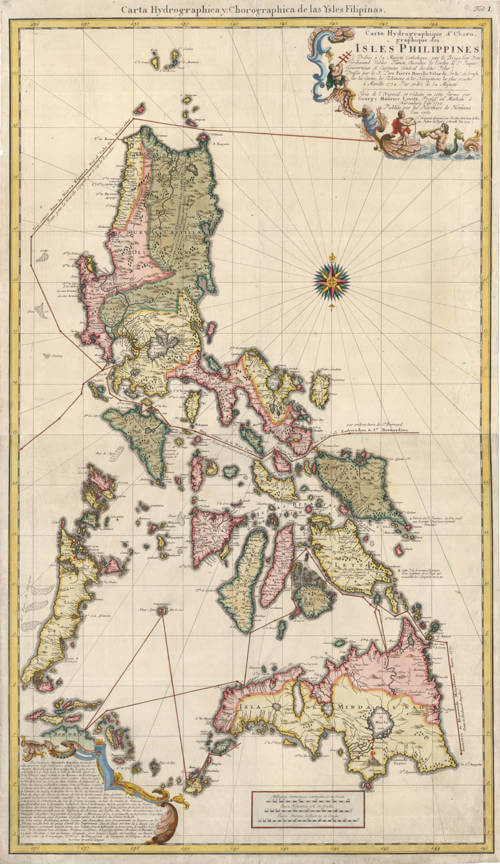

One of the most notable works from the Homann Heirs is the two-sheet sea chart of the Philippines, produced in 1760 in collaboration with Nuremberg professor George Maurice Lowitz. This map, titled "Carte Hydrographique & Chorographique des Isles Philippines," represents an exceptional piece of nautical cartography for its time. It provides a detailed depiction of the Philippine archipelago, including the major islands like Luzon and Mindanao, along with navigational aids like compass roses, rhumb lines, and a wealth of information on maritime routes, sea depths, and coastal features. The map also reflects the geopolitical knowledge of the era, showing Spanish influence in the region. This chart was both a navigational tool for sailors and a testament to the Homann Heirs' commitment to advancing the accuracy and detail in cartography.

Their business strategy was also ahead of its time, capitalizing on lower production costs in Germany compared to other countries, thus gaining a competitive edge in the market. The Homann maps often included innovative features like detailed city plans within larger regional maps, catering to both scholarly and commercial audiences.

The legacy of the Homann family extends beyond their lifetime; their maps are now cherished by collectors and historians for their historical and artistic value. The Homann Heirs continued until 1852, leaving behind a vast collection of maps that chronicle not just geography but the evolution of cartographic art and science in the 18th century. The Homann family's work from Nuremberg serves as a testament to the era's cultural and scientific achievements, encapsulating the spirit of an age where exploration and knowledge were paramount.