Leen Helmink Antique Maps

Old books, maps and prints by Frederick de Wit

Frederick de Wit (1629-1706)

Early Life and Beginnings in Amsterdam

Frederick de Wit was born around 1629 in Gouda, a city known for its cultural and intellectual contributions during the Dutch Golden Age. His family was Protestant, and by 1648, 18 or 19 year old De Wit had moved to Amsterdam, a city at the heart of Dutch trade, culture, and mapmaking. Here, he served his apprenticeship under the tutelage of Joan Blaeu, whose family was already famous for producing some of the world's finest atlases and maps.

Establishment in Amsterdam

In 1654, de Wit set up his own printing office and shop, initially named "De Drie Crabben" (The Three Crabs), which was also the name of his residence on Kalverstraat. The following year, he renamed it "De Witte Pascaert" (The White Navigation Chart), signaling his focus on cartography. His early works included a plan of Haarlem in 1648 and illustrations for Antonius Sanderus’s "Flandria Illustrata", but it was his independently engraved map of Denmark in 1659 that marked his entry into the broader mapmaking world.

Cartographic Contributions and Style

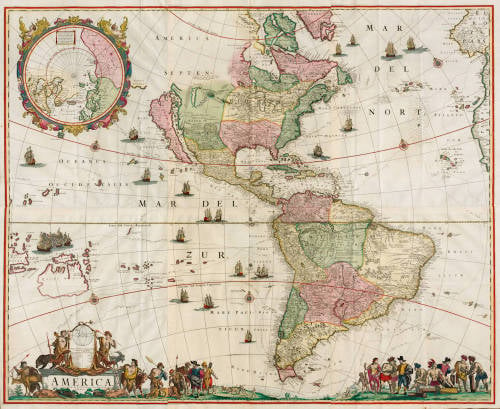

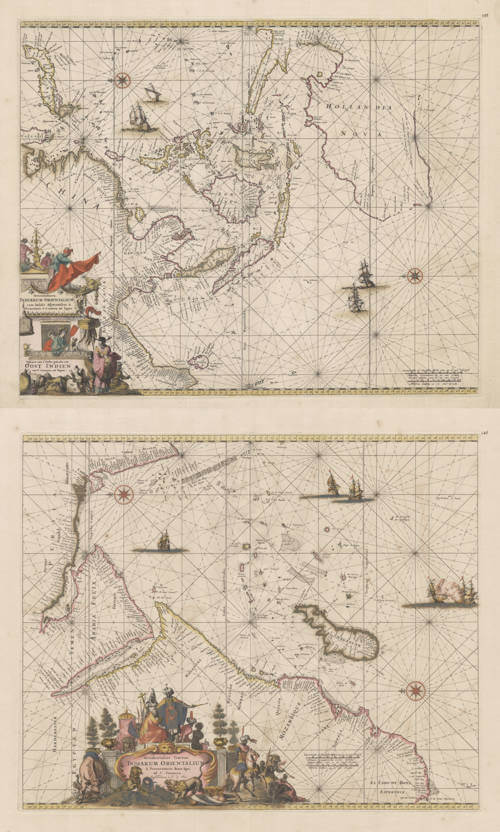

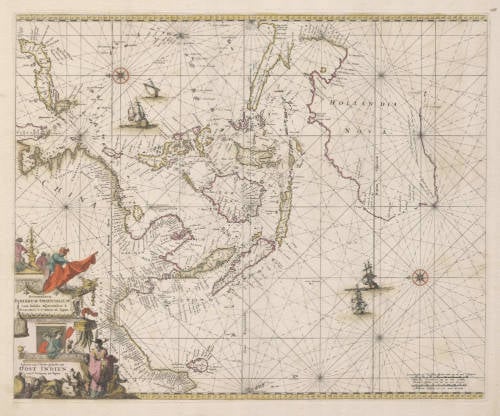

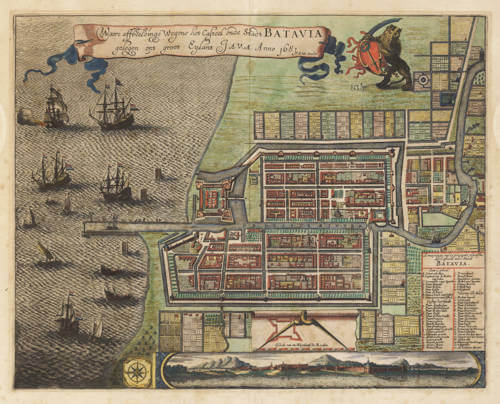

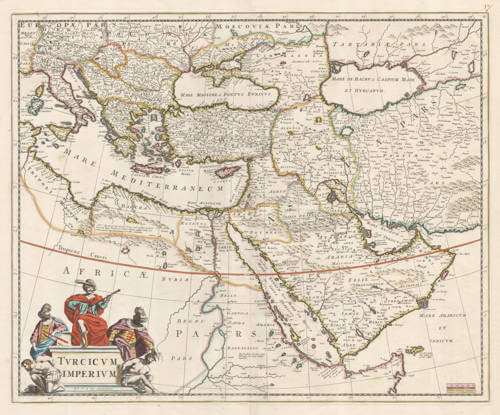

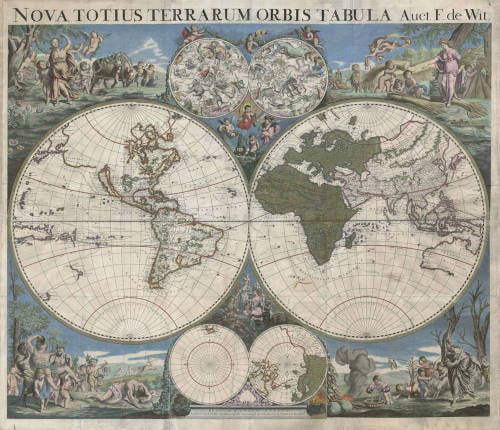

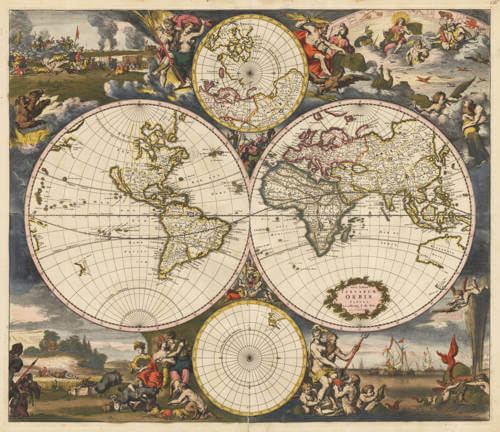

De Wit's maps were distinguished by their accuracy, decorative borders, and elaborate cartouches often depicting classical mythology or allegorical scenes. His most famous work, "Nova Totius Terrarum Orbis Tabula," was a world map first published in 1660. The map demonstrated his skill in both geography and artistic design. Over the decades, he produced numerous sea charts, town plans, and wall maps, which were not only navigational aids but also sought after for their beauty and decorative value.

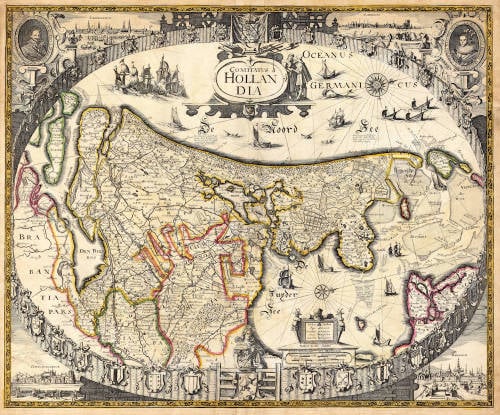

By the 1670s, de Wit was producing larger atlases like the "Atlas Maior" and "Nieuw Kaertboeck van de XVII Nederlandse Provinciën". These atlases combined his own engravings with those he had acquired, showcasing his entrepreneurial spirit. His maps of the Netherlands were particularly notable for their detailed depiction of the Dutch landscape, including cities, waterways, and dykes, reflecting the country's complex relationship with its environment.

Personal Life and Guild Membership

In 1661, de Wit married Maria van der Way, which not only brought him personal happiness but also the privileges of Amsterdam citizenship. This allowed him to join the prestigious Guild of Saint Luke in 1664, which was essential for artists and engravers in the city. His involvement with the guild underscores his standing in the artistic community of Amsterdam.

Later Years and Legacy

De Wit's business thrived, especially after the death of his mentor Blaeu, from which he acquired many copper plates when they were dispersed at auction, positioning him as one of the leading cartographers in Amsterdam. He continued to expand his catalog, ensuring his maps were up-to-date with the latest geographical discoveries. His attention to detail and the aesthetic quality of his work made his maps popular among the elite, scholars, merchants, and navigators alike.

When Frederick de Wit passed away in July 1706, his wife Maria managed the business until 1710. After her death, the vast collection of copper plates was auctioned off, with many going to Pieter Mortier (1661-1711), who used them to further his own publishing empire, Covens & Mortier. In 1721, the copperplates were sold in auction by the heirs of Mortier's widow, and were acquired by the Ottens publishing house in Amsterdam. These transactions illustrate de Wit's lasting influence on the mapmaking industry.

Cultural Impact and Modern Appreciation

De Wit's work encapsulates the spirit of the Dutch Golden Age – a period of unprecedented artistic and scientific achievement. His maps are not merely tools for navigation but are also pieces of art that reflect the cultural pride of the Dutch in their maritime and cartographic prowess. Today, his maps are treasured in collections around the globe, from libraries to smaller, specialized map collections. They are frequently exhibited in museums as exemplars of the Dutch art of cartography, admired for their precision, beauty, and historical significance.

Frederick de Wit's legacy is one of a craftsman whose maps not only charted the physical world but also captured the imagination of those who used them, contributing to the enduring allure of an age when maps were as much about exploration as they were about art.