Leen Helmink Antique Maps

Amerigo Vespucci Discovering the Southern Cross with an Astrolabium, by Johannes Stradanus

Stock number: 19565

Zoom ImageCartographer(s)

Johannes Stradanus (biography)

Title

Astrolabium.

First Published

Antwerp, 1588

This Edition

1588 FIRST STATE

Size

20.2 x 26.5 cms

Technique

Condition

mint

Price

$ 2,750.00

(Convert price to other currencies)

Description

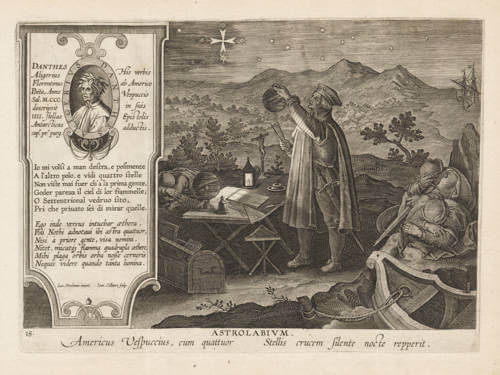

ASTROLABIVM. Americus Vespuccius, cum quattuor Stellis crucem silente nocte repperit.

"ASTROLABE - Americus Vespuccius found the cross with the four stars in the silent night."

Iconic engraving by Philip Galle of the invention of the astrolabe and the discovery of the Southern Cross, after a drawing by Jan van der Straet (Stradanus).

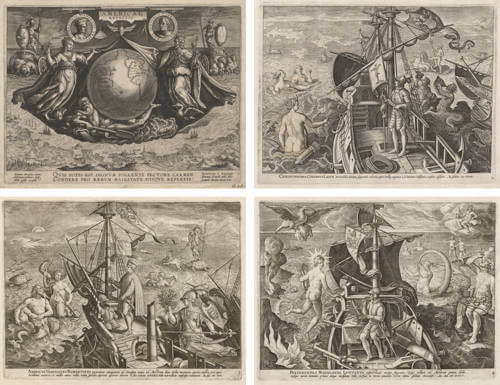

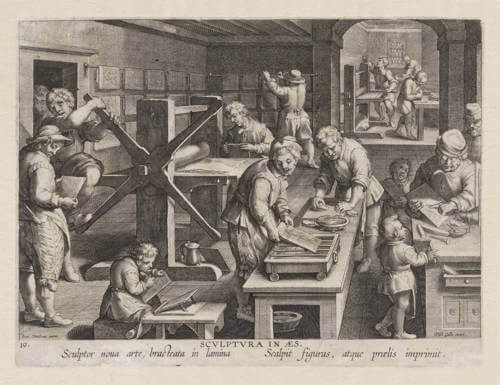

The drawing became widely known in early modern Europe through the famous print offered here, where it was used by the Antwerp engravers Theodore and Philippe Galle in collaboration with Jan Collaert as one of the images in their Nova Reperta, or New Discoveries, a portfolio of twenty prints first published around 1591. The prints documented a series of discoveries and inventions, such as gunpowder, the printing press (this one here), olive oil pressing and eyeglasses.

Stradanus's Astrolabe

While the sailors sleep, Vespuccius, astrolabe in hand (actually, he is shown holding a small armillary sphere), discovers the Southern Cross and applies to his discovery the famous words of Dante in the Divine Comedy (Purgatory, Canto I, 22-27) in which he says he saw the four stars. The Italian text and its Latin translation are given at the left.

(Burndy Library)

The "Astrolabium" engraving presents a scene featuring the Florentine explorer Amerigo Vespucci, emphasizing the astrolabe's role in celestial navigation:

Central Figure: Amerigo Vespucci is depicted holding an astrolabe, gazing upward toward the night sky. His attentive posture signifies the instrument's crucial function in stellar observation and navigation.

Foreground: A table is set before Vespucci, adorned with various tools and a candle providing illumination, symbolizing the meticulous nature of astronomical studies.

Background: The scene unfolds against a landscape featuring mountains and an ocean, underscoring the broader context of exploration and discovery.

Additional Elements: At the scene's periphery, men are depicted sleeping with their hands covering their faces, indicating the tireless endeavors of explorers and scholars during nocturnal hours.

This composition not only showcases the astrolabe's significance but also reflects the era's dedication to expanding geographical and astronomical knowledge.

Nova Reperta

The print series »Nova reperta« (New inventions), which Stradanus drew in the third quarter of the 16th century, is a rich source for cultural history in general as well as for the history of technology in particular. The discoveries and inventions depicted here extend throughout the Middle Ages and the Renaissance epoch, but the workshops and the people in them generally belong to the artist's time.

The major technical developments of the high Middle Ages include the widespread expansion of the water wheel, which was already known in antiquity, and the introduction of the windmill in Europe. The author commemorates both engines (water wheel, wind wheel) his picture series. Together with the now also better-used animal force they helped to establish a civilization in the Middle Ages that no longer mainly used human muscle as it did in classical antiquity, but that learned more and more to make use of other forces with technical means. The mechanical clock and the spectacles, two inventions of the 13th century, which influenced the bourgeois life substantially, are shown to us in two particularly attractive pictures. The great inventions of the late Middle Ages, gunpowder and book printing, are also treated, but oil painting and the art of copper engraving are not forgotten either. In the fields of chemistry and chemical technology, the images include distillation, sugar and oil paint. The art of distillation had made significant progress since the high Middle Ages. The artist also devotes some quite compelling images to the geographical discoveries and their technical requirements. From a technical-historical point of view, the draftsman has really chosen the most essential inventions of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance as a theme.

The illustrator of the sheets is Bruges-born Jan van der Straet (1523-1605), who in Latin was called Stradanus and in Italian Stradano (or della Strada). Stradanus, painter and draftsman, worked mainly in Florence, where he belonged to the circle of the artist and art writer Giorgio Vasari. Like Vasari, Stradanus moved in the path of late Renaissance mannerism. Characteristic of the mannerism of Stradanus is the abundance of juxtaposed details, the extensive joy, the fragmentation of the space, the narrowness and compression of the images (for example the distillation print), the use of the picture in picture (for example the guaiac wood print) and the contortion of the figures (for example the copper engraving print).

From his Flemish motherland Stradanus brought with him the strong inclination for the powerful and the realistic depiction. Vasari praised Stradanus’ great drawing skills, his excellent ideas and his ingenuity. In the extensive work of Stradanus comes out a variety of pasteboards, which he delivered to the wall carpet manufacturer for the Medici family in Florence. Especially his hunting scenes made Stradanus famous. We encounter his paintings and frescoes mainly in Florence, such as in Palazzo Vecchio, where we also admire, among other things, his 1570 created painting of a distillation laboratory of Grand Duke Francesco I de 'Medici. The picture resembles the sheet "Distillatio”.

The drawings for the series "Nova reperta" were created by Stradanus in the third quarter of the 16th century. At the end of the 16th century, the Amsterdam draftsman, engraver and engraver Philipp Galle had nine of these drawings and a title page engraved in copper by his son Theodor Galle. It was soon followed by another ten leaves that were engraved by Theodor Galle and Jan Collaert. On all engravings Stradanus is a draftsman (Inventor), indicated with »Ioan. Stradanus invent«. The engravers Theodor Galle and Jan Collaert (Inscribed "Theodor Galle sculp.", "loan Collaert sculp.") are only mentioned on some of the engravings.

(Klemm)

Stradanus' Astrolabium

In the 15th century, the Southern Cross, part of the constellation Crux, was notably observed by European explorers during their voyages. Amerigo Vespucci is often credited with being one of the first Europeans in the modern era to document this constellation during his voyages to South America. Specifically, during his third voyage in 1501, Vespucci observed and noted the Southern Cross, which he referred to as "four stars" in his accounts. His observations and writings helped establish the constellation's significance for navigation in the Southern Hemisphere. However, it's worth noting that while Vespucci may have popularized the Southern Cross among Europeans, the constellation was known to ancient civilizations like the Greeks and the Incas, and it was already used by Portuguese sailors for navigation before Vespucci's voyages.

The bright stars in Crux were known to the Ancient Greeks, where Ptolemy regarded them as part of the constellation Centaurus. They were entirely visible as far north as Britain in the fourth millennium BC. However, the precession of the equinoxes gradually lowered the stars below the European horizon, and they were eventually forgotten by the inhabitants of northern latitudes. By 400 AD, the stars in the constellation now called Crux never rose above the horizon throughout most of Europe. Dante may have known about the constellation in the 14th century, as he describes an asterism of four bright stars in the southern sky in his Divine Comedy.

Dante and Vespucci

Dante Alighieri, known for his monumental work, "The Divine Comedy," composed in the early 14th century, has long intrigued scholars with his apparent reference to the Southern Cross, a constellation not officially "discovered" by Europeans until the late 15th century. In "Purgatorio," the second part of his epic, Dante describes "four stars not seen before except by the first people" (Purgatorio I.23-24), which many interpret as a nod to the Southern Cross, or Crux, a constellation visible only in the southern hemisphere.

The mystery of Dante's knowledge stems from the fact that during his lifetime, the Southern Cross was not visible from the latitudes of Europe due to the precession of the equinoxes, a gradual shift in the orientation of Earth's axis that changes the position of constellations in the sky over millennia. The Crux had moved out of Mediterranean view by Dante's time, making his mention of it particularly curious.

Dante's work is steeped in layers of symbolism, allegory, and historical reference, making it challenging to ascertain with certainty how he knew of the Southern Cross. His "Divine Comedy" is not just a voyage through the afterlife but a tapestry woven with the threads of medieval science, philosophy, and theology. While we may never fully unravel all of Dante's sources or inspirations, the inclusion of the Southern Cross adds to the rich enigma of his genius, suggesting a man whose knowledge and imagination transcended the geographical and temporal boundaries of his time.

Transcription and translation of the panel texts

DANTHES Aligerius Florentinus Poeta, Anno Sal. M.CCC. descripsit IIII. Stellas Antarcticas cap. pr. purg.

His verbis ab Americo Vespucio in suis Epistolis adductis.

Dante Alighieri, Florentine Poet, in the year of Salvation 1300, described four Antarctic stars in the first chapter of Purgatory.

With these words brought forth by Amerigo Vespucci in his letters.

Italian:

Io mi volsi a man destra, e posi mente

A l'altro polo, e vidi quattro stelle

Con viste mai fuer ch'a la prima gente.

Godër parea lo ciel di lor fiammelle;

O Settentrional vedovo sito,

Pria che privato sei di mirar quelle.

Latin:

Ego inde versús intuébàr æthera,

Poli Nothi adnotaui ibi astra quatuor,

Nisi a priore gente visa nemini.

Nitet, micatqz flamma quadrupla æthere,

Mihi plaça orbis orba nobis cerneris

Nequis vidère quando tanta lumina.

The Italian text is directly from Dante's "Purgatorio," describing his vision of the four stars in the southern sky, which are widely interpreted as the Southern Cross.

The Latin text is a scholarly annotation or commentary, providing a parallel description or interpretation of Dante's verses, emphasizing the rarity and significance of seeing these stars, traditionally visible only in the southern hemisphere.

English (from Italian):

I turned to the right hand, and set my mind

To the other pole, and I saw four stars

With a sight never seen except by the first people.

The sky seemed to rejoice in their little flames;

O Northern widowed place,

You were deprived before of seeing these.

English (from Latin):

From there, I looked up at the sky,

I noted four stars of the southern pole,

Seen by no one except the earlier people.

It shines, and the quadruple flame sparkles in the sky,

The pleasing part of the world, now deprived of stars, as you seem to me

No one could see when such lights shone.

The voyager as a scholar.

Amerigo Vespucci in Early Modern graphical representation

Stradanus developed a whole catalogue of illustrations that depicted all recent European inventions: printing press, compass, spectacles, clockwork, distillation, etc. Amerigo Vespucci is repeatedly honored in this work, once again mentioned as the representative of Florentine science and culture.

As Mauro has shown, Vespucci notes in a letter to Lorenzo Pier Francesco Medici how he tried to find a fixed star in the southern sky that could be used in determining the direction, but the search was unsuccessful. He writes:

"Even though I had worked so many nights and with so many tools – the quadrant and the astrolabe – I could not identify a star that had less than ten degrees of motion around the sky; that is why I did not name any of them the austral pole because of the large movement they all made around the firmament".

But suddenly, Vespucci remembers a passage from the Divine Comedy, and thanks to the words of Dante, he can recognize the Southern Cross:

And continuing this work, I remembered some lines of our poet Dante, mentioned in the first chapter on the Purgatory, when he imagines leaving this hemisphere and wanting to describe the Antarctic pole on the other:

I turned right, and well in front of

the southern pole,

I saw the four stars

never again seen since the very first people.

The sky was full of their brightness:

You northern widower are not allowed

to see such stars!

Vespucci's words are cited in this master print of the Nova reperta series in which the existence and knowledge of the constellation are confirmed by the author of the Divine Comedy. As Alessandra Mauro emphasizes, the authority of Dante is sufficient for this identification, since experience finds its proof in the poetic tradition.

We thus see Vespucci at work while observing the sky and the stars in the moonlight. On the table beside him there are a lamp, some paper, ink, a globe, a crucifix, in other words all that is needed for a scholar and a scientist to study the world. Next to him, two soldiers are sleeping, recalling the biblical scene on the Mount of Olives and establishing thus an analogy to how revealing has been his work.

Worth mentioning is also the fact that in 1508 Amerigo was appointed by the Board of Burgos as a Piloto Mayor, when the position of a chief pilot was created. This appointment confirms his excellent skills as cosmographer, a position he held for four years until his death on 22 February 1512. Vespucci has to be considered a pilot with a significant curriculum, both concerning the practice of sailing and the teaching of cosmography, especially in the determination of latitude on the high seas by using the astrolabe, tables of solar declination and the so-called regimento of the Sun. Vespucci was the first to formulate the existence of a new world on the other side of the Atlantic. While Christopher Columbus had eagerly sought the islands mentioned by Marco Polo, Vespucci had the exact notion of being in a totally unknown territory. Aware of this fact, Vespucci baptizes the unknown as such and thus his name will be associated to the newly discovered land.

(Marília dos Santos Lopes)

Rarity

All Stradanus prints are of exceptional rarity and lacking in nearly all collections.

Significance

The print is of highest importance to the discovery of the Southern Cross and the early exploration of the Southern Hemisphere. The astrolabe was instrumental in advancing navigation techniques, enabling explorers like Vespucci to traverse uncharted territories and contribute to the mapping of the world.

Condition description

FIRST STATE, in mint condition. New Hollstein 326 state I (of III). A strong and early imprint from the copperplate. No paper restorations or imperfections. Pristine collector's example of this attractive and significant master print.

Johannes Stradanus (1523-1605)

Johannes Stradanus, or Giovanni Stradano, or Jan van der Straet or van der Straat, or Stradanus or Stratensis (Bruges 1523 – Florence 2 November 1605) was a Flanders-born mannerist artist active mainly in 16th century Florence, Italy. Born in Bruges, he began his training in the shop of his father, then in Antwerp with Pieter Aertsen.

By 1545, he had joined the Antwerp guild of Saint Luke or painters' guild, the equivalent of the Roman (Accademia San Luca). He reached Florence in 1550, where he entered in the service of the Medici Dukes and Giorgio Vasari. The Medici court was his main patron, and he designed a number of scenes for tapestries and frescoes to decorate the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence, the Medici Villa at Poggio a Caiano, and providing illustrations for the Arazzeria Medicea. He also worked for the Pazzi Family in their estates in Montemurlo.

Many of his drawings became so popular they were translated into prints. Stradanus collaborated with printmakers Hieronymus Cock and the Galle family in Antwerp to produce hundreds of prints on a variety of subjects. He also worked with Francesco Salviati in the decoration of the Vatican Belvedere. He was one of the artists involved in the Studiolo of Francesco I (1567-1577), to which he contributed two paintings including "The Alchemist's Studio".

Karel van Mander wrote about Stradanus in his Schilder-boeck (book of famous painters), mentioning that he was 74 in 1603 and still a member of the Florence drawing academy. He also mentioned his pupil Antonio Tempesta, who painted ships and Amazon battle scenes (bataljes), mainly in 16th century Florence, Italy.

Johannes Stradanus is one of the most well-known unknown artists in history. Even though the Bruges-born painter (1523-1605) had a more than successful career in the highly competitive city of Florence in the second half of the 16th century, his name long remained a well-hidden secret for specialists only. Many of his works, though, are very well known.

Around 1570, Stradanus – who began as designer of tapestries and fresco painter in service of the Medici – started a second career as draughtsman and designer of hundreds of prints. These were engraved, published and distributed all over the then-known world by Antwerp publishers in huge numbers. It are these works – widely collected, copied and used – which secured Stradanus’s place in art history as an inventive and influential artist.

Johannes Stradanus died in Florence in 1605.

Literature

New Hollstein (Dutch and Flemish) 342-345 (Johannes Stradanus).

Stevens & Tooley: Map Collector 2, p.22-24, "One of the Rarest Picture Atlases".

van Mander: Schilder-boeck, 1604.

Sellink: Stradanus (1523-1605), Court Artist of the Medici, 2008.

Markey: Renaissance Invention - Stradanus's Nova Reperta, 2020.