Leen Helmink Antique Maps

Willem Blaeu wall map of Asia in presumably the only complete first edition of 1608

The item below has been sold, but if you enter your email address we will notify you in case we have another example that is not yet listed or as soon as we receive another example.

Stock number: 19407

Zoom ImageTitle

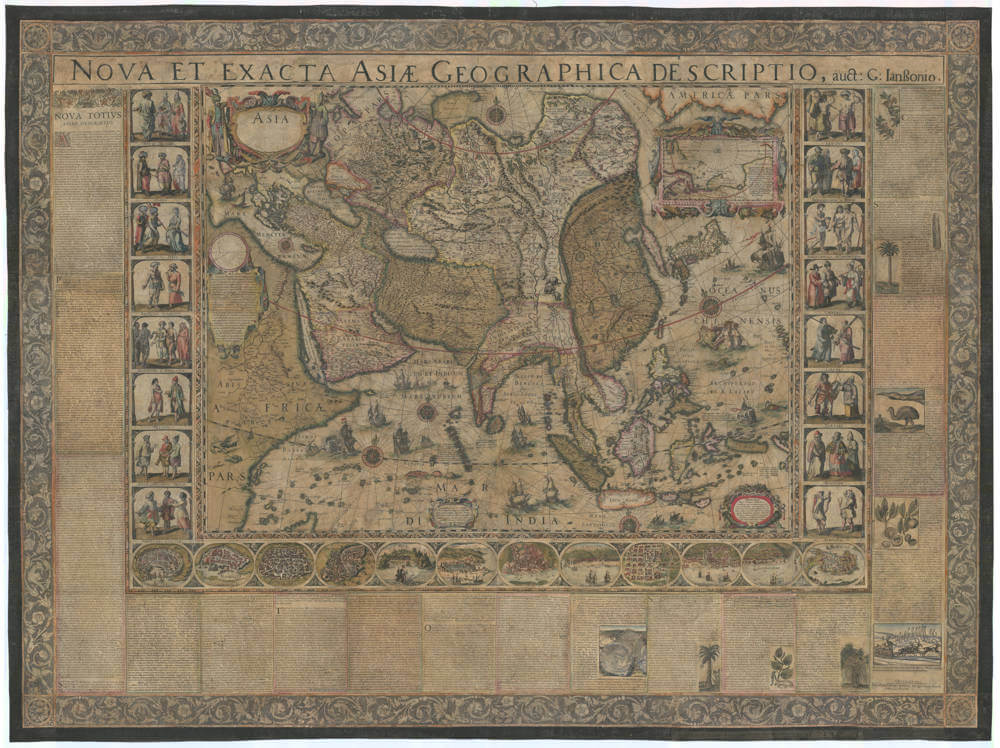

Nova et Exacta Asiae Geographica Descriptio, auc: G: Ianssonio.

First Published

Amsterdam, 1608

This Edition

Amsterdam, presumably the 1608 first edition

Size

131.5 x 180.3 cms

Technique

Condition

see description

Price

This Item is Sold

Description

The Most Important Map of Asia from the 17th Century

Only the Second Known Example of Willem Janszoon Blaeu’s Foundational Wall Map of Asia

Enter the Dutch in the Indian Ocean theatre:

Asia at the Foundation of the VOC and the Discovery of Australia

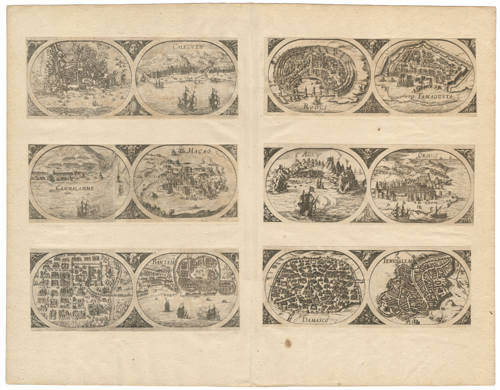

An exceptionally rare and impressively large wall map, of high aesthetic appeal, comprising four mounted copper engraved map-sheets, surrounded on three sides by sixteen etched ethnographic images of the various people of Asia, twelve etched bird eye views of cities of Asia, including the newly founded VOC trading posts of Bantam and Ternate. Elaborate letterpress text panels in Latin, describing the various regions of Asia, the history, the people, cultures, and exotic products, decorated with 10 woodcuts of flora, fauna, and spices. Large paste-on title along the top. Inside the map, the Indian and Pacific Oceans are embellished with sea monsters, compass roses, mermaid and mermen, VOC East Indiamen, Portuguese and Spanish carracks after Brueghel, Turkish galleys, as well as Asian sampans and merchant ships with rotan sails and wooden anchors. With a mall inset map of the northeast passage to get to the spice islands along the north. The whole wall map is surrounded by a floral border and mounted on linen.

Overall size with text panels, title strip and border: 1315 x 1803 mms.

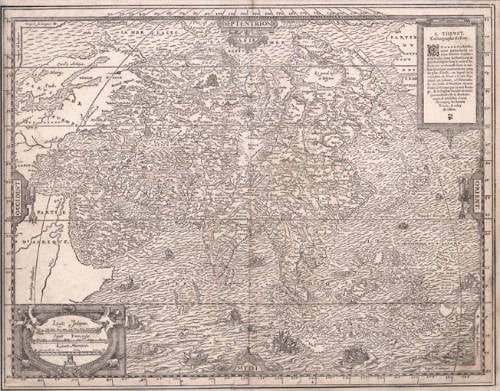

Willem Janszoon Blaeu's magnificent wall map of Asia stands as a seminal cartographic masterpiece of the 17th century. It not only holds the distinction of being the most significant map of the Asian continent during that era but also served as the blueprint for numerous subsequent maps of Asia in the following century. This extraordinary map offers a glimpse into the Dutch perspective on the East during the formative years of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) when their sprawling trading empire was in its nascent stages. Remarkably, this map is the earliest surviving example of Blaeu's circa 1609 continental map; only one other example issued by Blaeu is at the Sächsisches Hauptstaatsarchiv, Dresden (Schr. II, Mappe 32 b, Nr. 3).

The map shows Asia in the greatest detail of any contemporary map, utilizing Portuguese charts and sources from the recent Dutch expeditions to the East Indies. It stretches from Egypt to the Marianas in the Pacific (Islas de las Velas alias Ladrones) and from the Arctic to Java.

Dating the Map

The cartouche situated in the lower right corner of the map bears the date 1608, signifying the moment when Willem Janszoon Blaeu was granted the privilege to publish his cartographic materials. However, it's noteworthy that Hessel Gerritsz, the artist responsible for etching the decorative elements, including the borders, had already parted ways with the Blaeu workshop by that time. This implies that the map's creation commenced before 1608, given Gerritsz's involvement.

Furthermore, the Arctic inset found in the upper right corner of the map provides a crucial dating clue. It references Henry Hudson's voyage in search of the Northeast Passage but omits his subsequent turn west towards North America. Henry Hudson left the Netherlands in early April 1609, suggesting that the map was not completed until at least mid-April 1609. Consequently, this map reveals a more intricate timeline than conventionally acknowledged. While the continental map set is typically dated to 1608, this map's genesis spans several years, with its initial publication occurring in the spring of 1609.

This map includes the original Blaeu imprint in the bottom right of the text, near the image of the sleigh drawn by reindeer. It does not include a date. The second state of this map carries a date of 1612. On 1612 states, the word “Amstelodami” is registered differently and is underlined only partially, while this example has a solid line extending across the entirety of the column. These and other differences in the text setting (compared with the Dresden example) suggest that this is an earlier state. The two examples typically cited as first states—those at the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris and the Rittersaalverein in Burgdorf—have neither the decorative borders nor the texts; so they cannot be dated definitively as early states. This indicates that the present example is the earliest example of its lineage.

Blaeu uses paste-on letterpress text panels that recount a wealth of detailed old and new information about all parts of Asia. Like printed books and pamphlets, such panels were created by the bookprinting presses of the Blaeu publishing house. While the text is identical to the text of the Dresden 1612 second edition of the wall map, here it has a different typesetting, suggesting that the wall map here is a first edition.

Contents and sources

The dreams and labours of Petrus Plancius and Jan Huyghen van Linschoten culminated in the Dutch First Fleet to the Indies taking place from 1595 to 1597. It was instrumental in the opening up of the Indonesian spice trade to the merchants that would soon form the United Dutch East India Company (VOC). This famous pioneering voyage, commanded by Cornelis de Houtman, would abruptly end the Portuguese Empire´s trade monopoly for the East and it would dramatically change the Indian Ocean theatre, notably the balance of power and the rules of trade. Right from this first voyage onward, the Dutch were going to dominate the East Indies and its trade for more than 200 years, and the Dutch were to stay in the area for more than 350 years.

The map offers a well-researched overview of Asia as understood in Amsterdam at the start of the 17th century. The Great Wall of China is included, as are many narrative notes borrowed from voyage and travel accounts as old as Marco Polo's and as recent as the first Dutch voyages to the East Indies and Japan at the turn of the seventeenth century. The Dutch were expanding their trading empire at this time and starting to dominate the map trade. When this map was made in the first decade of the seventeenth century, the Dutch were making inroads in the East Indies spice trade and the China trade in places like Macao. The map does not include the Duyfken's 1606 first landfall in Australia, a secret VOC expedition that was not yet known to Willem Blaeu in Amsterdam.

Inland areas are thickly blanketed with towns, mountain ranges, deserts, and other features. For example, the Arabian Peninsula shows many settlements ringing the coasts before giving way to a desert interior. It also has sites that are still familiar today. These include Bahrem (Bahrain), M. Sinai, Mecca, and Medina. The Gulf is labeled Mare Elcatif olim Sinus Persicus.

The map shares many details with Blaeu’s 1605 world map. Both show the Strait of Anian (see below). Southeast and East Asia are drawn from Portuguese maps and charts. The Ganges is shown on a mistaken course and there are no Himalayas, underlining that there was much still to be learned. Indeed, the Malaccan Peninsula and the Gulf of Siam are more precise and detailed here than on the 1605 world map, showing how Blaeu was improving his geography in a few short years. Similarly, Korea is still shown as an island here, but it is elongated rather than circular (see below).

On the Malaccan Peninsula is Sincapura, or Singapore. At this time, the name referred to a trading settlement, although the town had earlier ties to both the Kingdom of Siam and the Majapahit Empire. Soon after this map was made, in 1613, the Portuguese burned the settlement, making this a fleeting glimpse of the place in a time of transition.

Much here has been taken from the voyage accounts of Jan Huyghen van Linschoten. As a young man, Linschoten traveled the world as part of the Portuguese East Indies trade. In 1583, his brother secured him a position as the Secretary to the Archbishop of Goa, a Portuguese colony. While abroad, he kept a diary, and began collecting other travelers’ diaries and accounts upon his return.

In 1594, Linschoten set out with Willem Barentsz on an exploratory expedition to find the Northeast Passage. The crew had many adventures, including an encounter with a polar bear, which they killed while attempting to capture it. Eventually, the crews had to turn back because of ice, a situation that also happened with a similar expedition the following year. Upon his return, Linschoten published his journal from the Barenstz voyages. In 1595, he also published Reysgheschrift vande navigation der Portugaloysers in Orienten (Travel Accounts of Portuguese Navigation in the Orient) based on his research. The work includes sailing directions in addition to descriptions of lands still new to Europeans, like Japan.

The Arctic here is based on Linschoten and other recent exploration. Novaya Zemla and Spitsbergen were both drawn from the first two voyages of Henry Hudson in 1607 and 1608. The image of the reindeer and the sleigh, and of the “Samoiedae” are based on Linschoten’s account of his time with Barentsz. The inset is meant to show off these recent expeditions. The text translates as:

Four different times, viz. in 1594, ’95, ’96 and 1609, the Dutch bravely tried to locate a passage through the northernmost regions of Europe and Asia close to the North Pole in order to find an easier navigational route to Cathay and China. As the situation of these regions cannot be seen accurately enough, because they are not depicted in an overlapping way, we have decided to present them to the conscientious observer on a separate map. (Schilder, MCN, vol. V, p. 138).

In 1597, Linschoten published again, this time a description of the African coast. His most famous work, however, is Itinerario: Voyage ofte schipvaert van Jan Huyghen van Linschoten naer Oost ofte Portugaels Indien, 1579-1592 (Travel account of the voyage of the sailor Jan Huyghen van Linschoten to Portugese East India). It was published in 1596 by Cornelis Claesz, an associate of Blaeu’s in Amsterdam. It was quickly translated into English (1598), German (1598), and French (1610). Latin editions appeared in Frankfurt and Amsterdam in 1599. It also contained important, detailed maps by the van Langrens which formed the foundation for this map's depiction of the East Indies and for the information about spices and local animals.

Another text cartouche, this one in the interior of Africa, explains how to calculate distance with a pair of compasses. This indicates that, however ornate the maps were, they were intended for at least some practical use as well. The translation is:

The distances of places to be calculated with the pair of compasses. On a drawn circle AENMBSD, divided into 360 parts, and with a diameter ACB, the difference in longitude of two places must be subtracted, from A down; a radius should be drawn to the end of the count, here for instance D. Then the largest latitude must be drawn, from A upwards, where one ends in E. A perpendicular EF must be dropped on the underlying diameter AB. However, the smallest latitude must be subtracted from D in the direction of B. From that point, here G, a perpendicular GH is dropped on the radius DC. The distance of the points FH is cut off (from the diameter) from F in the direction of B, and this equals FK. Then, provided the latitudes are homogenous, (that is; both belonging to either the northern or the southern hemisphere), one cuts off EI, which equals the perpendicular HG, from the long perpendicular EF from E in the direction of F. Then the straight line IK (the connection between the points I and K) is the chord of the required distance of the places. If one draws this upwards from B to the circumference of the circle, the arc BM indicates how many degrees and consequently how many miles the places you postulated are apart from each other. If the latitudes are heterogenous, the straight line FE must be drawn as far as L, so that EL equals the perpendicular GH. Then KL is the chord of the distance you asked. You draw it upwards to the circumference of the circle and BN provides the distance of your places in degrees. (Schilder).

Decorative elements

Blaeu’s continental maps are as renowned for their borders as they are for their geographic content. As stated above, the decorative elements were etched by Hessel Gerritsz, while the map was engraved by Josua van den Ende (he engraved all four of the continental maps, but his signature is only on the second state of the Africa map).

Decorative borders were not new in the early seventeenth century, but it is when they were popularized, by and large by Blaeu. Abraham Ortelius included some in his work in the 1590s, while Jodocus Hondius began to use them while in England in the same decade. They were first seen in Amsterdam thanks to the work of Van der Keere in 1596, but they were most successfully utilized by Hondius, back in Holland, and Blaeu. For example, there are superb borders on the former’s fifteen-sheet map of Europe (1595), the first to introduce costumed figures on the sides. They are also present on the latter’s twenty-sheet map of the world (1605), which adopted round and oval town views for the first time. The trend of decorative borders spread across Europe and lasted in the Netherlands until the 1660s.

The costumed figures shown here are drawn from a variety of sources including costume books, popular prints, and travel literature. The Chinese come from De Bry images, while the Japanese and the Marianas islanders are taken from De Noort’s voyage account. The Tartars are inspired by the prints of Eneo Vito, while the Muscovites are based on the work of Joost Amman. The Syrians are from Nicolas de Nicoloay and the Gujaratis from Linschoten.

The twelve town and city views also originate from travel writing and city books, especially Braun and Hogenberg’s Civitates Orbis Terrarum. Goa is from Linschoten, Bantam from the journals of De Houtman and Lodewijcksz on the first Dutch fleet to the Indies, and Gammalamme from Van Neck's journal on the second Dutch fleet to the Indies, reaching the Spice Islands.

Rarity and states

This map in any form is exceedingly rare and this is only the second known example to include the map, the decorative borders, and the text.

In volume V of Monumenta Cartographica Neerlandica (page 80), Schilder proposes two candidate examples as possible other first states of the 1608 (actually 1609, as explained above) Blaeu Asia; one in Switzerland ("Rittersaalverein, Burgdorf (Switzerland; mounted and stored in a paneled wooden locker)") and one at the BnF in Paris ("Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris (Ge C 4930 [ex Klaproth Collection, no. 745]; mounted)"). Both of these examples are comprised of only the four central cartographic sheets, having previously lost their side panels and text sheets.

Per Schilder's census, there is only one known complete example of the second state of Blaeu’s Asia, dated 1612 in the imprint line in the far lower-right. This is held at the Sächsisches Hauptstaatsarchiv, Dresden (Schr. II, Mappe 32 b, Nr. 3). However, as explained above, the imprimatur differs from the present example.

Sometime after 1612 but before 1625, the plates were acquired by Henricus Hondius, who published them in 1624 in a third state. In that edition, the text has been reset and the imprint line changed, but the geographical plates appear to have been untouched.

This raises an interesting point with respect to the Swiss and French examples noted by Schilder under his entry for the first state; if they lack side panels, it cannot be said if they were printed in 1608, 1612, or indeed 1624 by Hondius. Therefore, prior to the discovery of the present map, there was only one definitely attributable Blaeu edition of the map in the world, the example of the second state at the Sächsisches Hauptstaatsarchiv in Dresden.

A later state by Claus Jansz Visscher is known only from external evidence with no surviving examples (fourth state, pre-1632). Nicolaas Visscher produced two states; a fifth state (dated 1657) survives in one state, and a sixth (n.d.) is known in two institutional examples and one Sotheby's sales catalog from 1980.

All states of the Blaeu Asia map are very rare. However, the present map’s imprimatur suggests it is the earliest extant example. It is also the only complete early example, making it one of the most important cartographic offerings of recent years.

Popularity of the Willem Blaeu's wall maps of the continents

The 1608 wall maps of the continents were highly appreciated by his contemporaries.

Constantijn Huygens (1596-1687), the great 'uomo universale' of his time, personally saw to the the education of his sons Constantijn the younger (1628-1697, the later poet) age 11 and Christiaan (1629-1695, the later mathematician, physicist, astronomer and inventor) age 10 after the sudden death in 1637 of his wife. He wrote in his memoir on the education of his children that he had "mounted the four continents by Blaeu in his hallway where the kids often play, so that they will be fluent in Latin, in geography and in the history of the world".

Willem Blaeu’s wall maps remained very popular throughout the entire seventeenth century. Several re-engravings of this wall map were published in Italy and France between 1646-1686. In a Joan Blaeu stock catalogue of ca 1670, the four 1608 wall maps of the continents of his father are offered alongside his own 1659 wall maps of the continents!

Strait of Anian

This strait, believed to separate northwestern America from northeastern Asia, was related to the centuries-long quest to find a Northwest Passage connecting the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific. The rumor of this strait and a Northwest Passage in general inspired many voyages of discovery, including those of John Cabot, Sir Francis Drake, Gaspar Corte-Real, Jacques Cartier, and Sir Humphrey Gilbert.

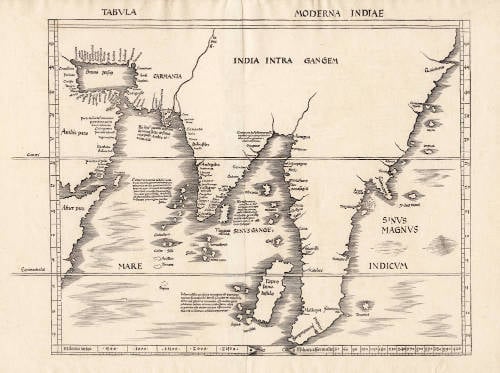

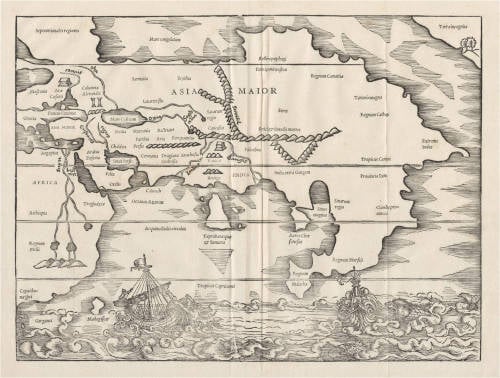

The term Anian itself comes from Marco Polo’s thirteenth-century accounts of his travels. Polo used the term to refer to the Gulf of Tonkin, but cartographers thought it could refer to this supposed strait between Asia and North America. The Strait of Anian, so named, first appeared in a 1562 map by Giacomo Gastaldi, and was later adopted by Bolognini Zaltieri and Gerard Mercator.

Korea as an island

The sequence of events and maps that led California to be portrayed as an island are much clearer than another famous peninsula-turned-island, Korea. Korea is briefly mentioned in the thirteenth century by Marco Polo as Cauli (Kauli), but otherwise Korea was not described again for European audiences until the late-sixteenth century.

As with Japan and China, most of the earliest bits of information about Korea came from the Jesuits sending letters sent back from East Asia. However, the Jesuits were not actually stationed in Korea; they could only glean impressions from Chinese and Japanese sources. For example, Father Luis Frois wrote of Korea in the context of a war with Japan in 1578. Frois explained that Korea was separated from Japan by a sliver of sea. It had previously been understood to be an island, he explained, but was now known to be a peninsula. However, why Korea was thought to be an island, by who, and how it was found to be a peninsula was not shared with Frois’ curious readers back in Europe.

The first known European to visit Korea was also a Jesuit, Father Gregorio des Cespedes. He accompanied Japanese troops during another war with Korea in 1592. The territory did not agree with Cespedes, who found it bitingly cold. He did not mention anything about the Korean peoples or their geography.

Travel writers, those who actually traveled and those who were more drawn to the armchair voyage, also wrote about Korea. Jan Huygen van Linschoten spent several years in Goa, India, where he had access to Spanish and Portuguese sources. In his Itinerario, first published in German and English in 1598, he suggests Korea is a large island called Core. Richard Hakluyt read the Jesuit letters, which were republished in sets of annual letters. In the second edition of his Principal Navigations (1599), Hakluyt included the information from Frois and Cespedes, scant as it was.

Given the relative dearth of source material, it is not surprising that early maps by Münster, Mercator and Ortelius omitted Korea entirely. The first map to show Korea was Orbis Terrarum Typus de Integro Multis in Locis Emendatus by Petrus Plancius (1594). It included “Corea” as a long, skinny peninsula barely attached to the northeast corner of China. Edward Wright, in the map accompanying Hakluyt’s Principal Navigations, adopted a similar depiction of Korea, as did other mapmakers from the 1590s onward.

Interestingly, the map that accompanied Linschoten’s Itinerario, by Arnold Floris van Langren, shows Korea as a large, round island. However, no other mapmaker is known to have followed this example. Another early island depiction that was widely adopted was that of Luis Teixeira in the 1595 edition of Ortelius’ Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. The long, thin island was used by several cartographers, including Jodocus Hondius, in the seventeenth century. Blaeu also used the Teixeira model before creating a new Korea in later maps that looked like a bat hanging from China, separated from the mainland by the thinnest of waterways.

Confusion over island vs. peninsula continued across seventeenth-century maps. For example, John Speed includes three separate versions of Korea across four maps in his A Prospect of the Most Famous Parts of the World (1626). It is shown on the Teixeira island model, as a thin peninsula, and as a blunt island. These various hypotheses as to the shape of Korea continued to coexist for decades.

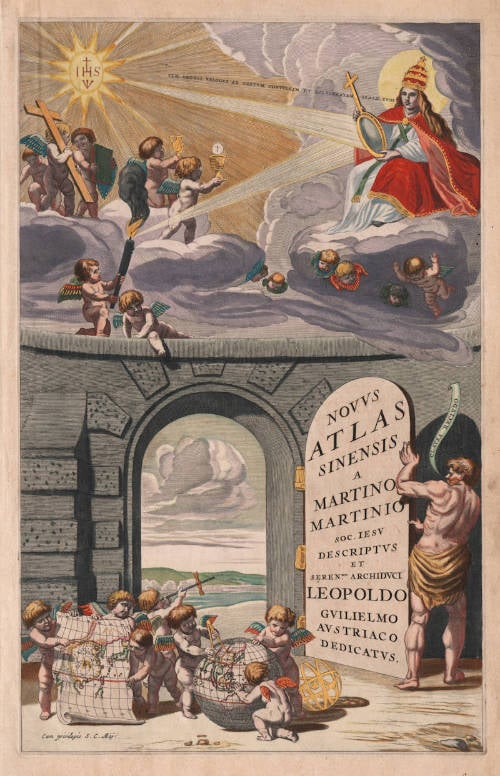

Finally, in the 1650s, Father Martino Martini gathered more information and created a new map of Korea. In China from 1642 to 1651, Martini spent a good deal of time with Chinese maps and their makers. Thus, he created new maps showing Korea as a thicker, nearly rectangular peninsula in Bellum Tartaricum (1654) and the Atlas Sinensis (1655).

Also in the 1650s, a Dutch sailor named Hendrick Hamel was shipwrecked on Jeju, an island near southern Korea. Hamel and his fellow survivors would spend thirteen years in Korea, escaping to Nagasaki in 1666. He wrote about the ordeal in a journal that was published in 1668. Although it lacked maps, the ample descriptions confirmed that Korea gave a detailed, first-hand view of Korean geography and culture.

Nevertheless, several maps were published in the early eighteenth-century showing Korea as an island. The island myth, which most likely stemmed from a misreading of Japanese and Chinese maps by early Jesuits, proved to be quite entrenched. Only in 1735 did Jean Baptiste Bourguignon d’Anville produce a map with a roughly accurate outline of the peninsula and a relatively detailed interior.

Condition description

Original hand-color retouched and augmented. Etching, engraving, woodcut, and letterpress on numerous sheets of early-17th-century laid paper joined as one and mounted on linen. Comprehensively and expertly restored. Substantial areas of facsimile, with areas of verdigris degradation most affected. Withal, presents as very good.

Survival of 16th and 17th century wall maps

It is highly unfortunate that only a few of these Dutch wall maps, which are documents of the highest cultural and historical value, have survived today. Of any particular wall map recorded in the literature, generally no more than a few examples are known today, but often no copies have survived at all.

The reason for this is that these decorative multi-sheet wall maps were mounted on linen and attached to wooden rollers, and then used as decorative show pieces to beautify the meeting rooms of executive councils and the interiors of large patrician mansions. Apart from being show pieces, such wall maps also served to give a highly detailed overview of the regions shown.

As wall maps were used as large informative and decorative pieces, intended for display, and as they were mounted on linen, often varnished and then attached to rollers, they had little protection from the elements. These fragile cartographic items were inevitably doomed to perish. Light, humidity, temperature fluctuations, smoke and soot from fire places all had destructive effects. Furthermore, being made from paper they were subject to damage by insects and worms.

As a result we find today that few mounted wall maps have survived and that most of these cartographic treasures from the Golden Age of Dutch mapmaking, have been lost forever. The very few linen-mounted examples on rollers that have survived are generally in poor condition and incomplete. The Blaeu wall map of the world of 1645-46 for instance, the first printed map to show the Tasman discoveries, has only survived in one single example, in “very poor condition”. In recent years, this wall map has been properly restored.

It is therefore remarkable that an unrecorded and virtually complete mounted example of Willem Blaeu’s magnificent wall map of Asia has come to light.

Willem Janszoon Blaeu (1571-1638)

Joan Blaeu (son) (1596-1673)

Cornelis Blaeu (son) (?-c.1642)

Willem Jansz. [Blaeu] and his son Joan are the most widely known cartographic publishers of the seventeenth century. Born as the son of a wealthy herring merchant in Alkmaar North Holland, to Anna, a first cousin of Willem. Cornelis Hooft was merchant in oil, grain and herring and twelve times mayor of Amsterdam. He hoped that Willem would take over his business.

But Willem was more interested in mathematics, astronomy and other scientific matters, however, and in 1595 he left for Denmark to study with the astronomer Tycho Brahe on the island of Ven. Brahe had established here his own observatory as well as a workshop for the manufacturing of instruments and a printing office. This enabled young Willem to acquire both theoretical and practical knowledge and provided him with contacts among like-minded people. After his return to the Netherlands he applied himself to astronomy for several years in his native Alkmaar. Here he published his first cartographic work: a celestial globe according to the observations of Tycho Brahe.

At the end of the sixteenth century Willem Jansz. moved with his family to Amsterdam. He set up a shop in celestial and terrestrial globes and nautical instruments, since the rapid growth of seafaring opened a large market for these goods. Soon he was able to offer for sale globes in various sizes. In 1605 Willem Jansz. moved to a new location at the "Op ‘t Water" (today Damrak nr. 46), a house with the sign of in de Vergulde Sonnewijwyser ("in the Gilded Sundial"). Apart from the manufacturing globes, Willem Jansz. published numerous maps and charts in folio size, along with multi-sheet wall maps, town views, and historical prints, all of which are now very rare.

Willem Jansz. made an unmatched contribution to the fields of navigation and cartography. His "Het Licht der Zee-vaert", published in 1608, was of great consequence for navigation in European coastal waters. He used the same oblong-size like Waghenaer did in his "Thresoor der Zeevaert" (1592): the work was constructed in a series of chapters, adding to each chapter sailing-descriptions for a specific stretch of coast and the corresponding chart. The coastal profiles in woodcut have been included in the text of each chapter.

In 1618 another mapmaker, bookseller and publisher, Jan Jansz. (Joannes Janssonius) established himself on the Damrak next door to Willem Jansz.’s shop. Accusing each other of copying and stealing information, the neighbours became fierce competitors. In about 1621, Willem Jansz. decided to put an end to the confusion between his name and his competitor’s and assumed his grandfather’s sobriquet, (Blauwe Willem), as the family name; thereafter he called himself Willem Jansz. Blaeu.

Responding to Janssonius’s plagiarism of "Het Licht der Zeevaert", Blaeu published a new pilot-guide in 1623: the "Zeespiegel", a description of the seas and coasts of the Eastern, Northern and Western Navigation. Approximately the same coastal areas are described as in the older "Het Licht der Zeevaert", but in a much more elaborate way and with a far greater number of charts.

Apart from pilot-guides, Blaeu also published single-sheet charts, often printed on durable vellum. As example attention is here given to the so-called "West-Indische Paskaert", a chart of the Atlantic Ocean in Mercator’s projection, published about 1630. Despite the obvious advantages for navigation, the charts drawn on this projection were only gradually accepted by navigators.

Blaeu was nearing the age of sixty when in 1630 he published his first atlas of the world and began to compete with Henricus Hondius. For many years Blaeu toyed with the idea of publishing his own atlas of the world. The initial material for an atlas was in Blaeu’s hands in the form of his own folio-maps, which he had begun publishing in 1604. Blaeu’s plan gained momentum, however, when he succeeded in 1629 in purchasing a large number of copperplates that had belonged to the late Jodocus Hondius the younger. Blaeu quickly amended these plates by replacing Hondius’s name with his own imprint, a common procedure in those days. In 1630 Blaeu published the "Atlantis Appendix", using his own maps and the amended maps of Jodocus Hondius. The world atlas consists of 60 maps, but without a descriptive text. In 1631 a new world atlas was published , titled "Appendix Theatri A. Ortelii et Atlantis G. Mercatoris", provided with a Latin text and nearly hundred maps. The intention in publishing this atlas was to produce a supplement to the works of the two famous geographers. Henricus Hondius and his brother-in-law Joannes Janssonius immediately took steps in reaction to the publication of Blaeu’s "Appendix" and published amended atlas-publications.

The fierce competition between Blaeu and Hondius-Janssonius greatly influenced the further development of their atlas productions. Blaeu now intended to distance himself completely from Ortelius and Mercator and to publish an entirely new world atlas in four languages. In 1634 a German edition was published, which contains a number of unfinished maps, a sign that the work was done hurriedly in order to have the atlas published in time.

The extent of Blaeu’s ambitious plans for the world atlas is reflected in his preface, where he states that it is his intention to describe the whole world and to depict all the ports and seas, and therefore several other volumes of the atlas were to follow shortly. In view of these plans, Blaeu’s investment in a new printing shop in 1637 is not surprising. Yet Blaeu did not live to see the publication of a new volume. After his death the business was continued by his two sons Joan and Cornelis, the elder of whom had been collaborating on the atlas since 1631. In 1640 a third volume was published (Italy), in 1645 a fourth (England and Wales), in 1654 a fifth (Scotland) and finally in 1655, a sixth volume covered China.

In addition to his activities as publisher, Willem Jansz. Blaeu continued his scientific pursuits. His expertise won official recognition at his appointment as chart maker and examiner of navigating officers by the Amsterdam Chamber of the United Dutch East India Company (VOC).

Blaeu’s new position gave him access to the enormous map archives of the VOC. He performed the function of chart maker until his death in 1638. For his task he employed the four assistants of his deceased predecessor Hessel Gerritsz. Blaeus’s work was most probably limited – given his age – to the supervision of his employees in the manufacture of charts, to the supervision of content and to any alterations and improvements required. A steady stream of charts, required to equip the ships, must have left his workshop. Thanks to his position as chart maker of the VOC, Blaeu was able to expand his world atlas of Asia with new maps and gain the edge on his Amsterdam competitors, Hondius and Janssonius.

Willem Jansz. Blaeu died in October 1638, leaving his prospering business to his sons, Joan and Cornelis.

(Schilder)

Hessel Gerritsz (1581/82-1632)

Master engraver and Map Maker, who 'ruled' the Seas

Hessel Gerritsz. (1580/81) ranks among the most important and influential cartographers of the early-seventeenth-century Amsterdam. He started his career in Willem Jansz. Blaeu's workshop. About 1608 he established himself as an independent engraver, mapmaker and printer.

In his position as chart-maker of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and West India Company (WIC) he had access to the latest ship logs, he equipped the ships to the east and the west with the latest charts, and was the best informed cartogrepher of the era.

(Schilder)

"Unquestionably the chief Dutch cartographer of the 17th century."

(Keuning)

His fame as cartographer grew rapidly to the point that on 16 October 1617 he was appointed the first exclusive cartographer of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), probably the most strategic position a cartographer could have in those days. He got the position by recommendation of Petrus Plancius, chief scientist and advisor of the VOC, who did not get along with the more senior Willem Blaeu. Gerritsz kept this post until his death in 1632, after which the position was given to Willem Blaeu after all (Plancius had passed away in 1622).

(Wikipedia)

In 1617, Hessel Gerritsz. published a large wall map of Italy in six sheets. His model for the geographical content was the wall map published by Giovanni Antonio Magini (1555-1617) in 1608, which was a milestone in the seventeenth century Italian cartography.45 He gave his wall map an extra cachet by extending the map image with town views and costumed figures. The design of the costumed figures is attributed to Pieter Lastman (1583-1633), the exquisite execution betraying the hand of the master etcher Gerritsz.

Gerritsz.' wall map of Italy was copied shortly after publication by the publishing house of Willem Jansz. [Blaeu]. To protect himself against such plagiarism in the future, he requested a patent from the States General. On 27 January 1618, they granted him a general patent in which amongst other things it was forbidden in any way to reproduce, copy or distribute his maps, descriptions of lands and prototypes ('models') both written or printed. Such an extensive patent was highly unusual, in the most cases a privilege was granted for precisely defined publications. Hessel Gerritsz. was so highly regarded in 1617, that he received such an important privilege from the States General in January 1618, shown by his appointment as instructor in geography for the Councillors of the Admiralty at Amsterdam on 15 July 1617 and as map maker for the Chamber Amsterdam of the VOC on 16 October 1617. With both appointments his old employer Willem Jansz. [Blaeu] was passed over.

With the appointment of Hessel Gerritsz. as map maker of the Chamber Amsterdam – a function which he held until his death in 1632 – the VOC brought a driven person into the house who undertook the organization of equipping the ships with charts and navigational aids with vigour. The instructions issued to him by the Chamber Amsterdam in 1619, give a good insight into what was expected from a map maker of the VOC. Because all merchants, masters and pilots were obliged to deliver the journals, maps and drawings made during the voyage to him on their arrival in Texel, with the aid of this material he was able to improve and expand the charts for the navigation to and from the Indies. The influential position that Hessel Gerritsz. held in equipping the VOC ships with charts cannot be overrated, for within a very short period he developed certain prototypes of charts, which – with some small adjustments – were part of the standard equipment of a VOC ship, sometimes until the middle of the eighteenth century.

(Schilder)

Related Categories

Antique maps of the East India Company

Old Master Prints

Antique maps of Australia

Antique maps of Japan

Antique maps of China

Antique maps of the Philippines

Antique maps of Southeast Asia

Antique maps of India and Ceylon

Antique maps of the Middle East

Antique maps of Asia

Old books, maps and prints by Willem Janszoon Blaeu

Old books, maps and prints by Hessel Gerritsz