Leen Helmink Antique Maps

Painted map on vellum of Marco Polo's unknown Southland

Stock number: 19069

Zoom ImageCartographer(s)

after Marco Polo

Title

[ Oceano Orientale ]

First Published

Italy, 1600

This Edition

1600

Size

25.8 x 42.3 cms

Technique

Condition

faded

Price

$ 125,000.00

(Convert price to other currencies)

Description

A remarkable fragment of an Italian manuscript map depicting the unknown Southland, ca 1600

Condition

Oil painting on vellum. The painted image has become vague in visible light because of its use as a book binding. Under multi-spectral imaging the painting becomes visible, this would allow to create a modern artist reconstruction to display in conjunction with the fragment.

Summary

A unique map of Marco Polo's unknown Southland with the Indian Ocean and South East Asia, oil painting on vellum. Originally the lower right quarter of what was a manuscript map of the world map, made around 1600 in Italy. Most remarkable is that the interior of this Australian proto-continent is filled with images of trees, mountains, people and fabled animals. In addition, more than a dozen red city symbols along the coasts of the Southland as well as in the interior suggests that we are coping with a densely populated continent with many large sea ports. Despite being a fragment and faded, the painted chart must be regarded as an an unparalleled document of the hypothetical pre-history of the fifth continent and an extraordinary exhibit of the Italian artistic cartography.

Cartographic contents

The Italian origin is evidenced from the toponyms (Oceano orientale, Giaua maggiore), from the compass rose with Italian directions of the winds (S=Syroco; O=Ostro and L=Libeccio) and from the long Italian text in the unknown South Land.

The fragment has miraculously survived because it has been re-used as a book-binding. This has however frayed the oil paint, affecting the legibility of the map image.

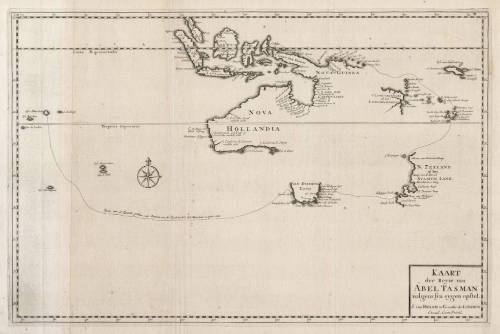

However, ultraviolet (UV) light imaging reveals attractive artwork all over the map and indicates that the map was made for decorative and informational purposes instead of for navigational use at sea. It is covered by a network of compass lines (loxodromes), covering the Indian Ocean as well as the South Land. The cartographic image covers the Indian Ocean, with the archipelago of south east asia in the upper right, and an immense South Land from the lower left up to the center right where it joins New Guinea. Shown with names are the islands of Java (Giava Maggiore), Borneo (Borneo) and Java Minor (Giaua Minor), and shown unnamed are Sumatra and the Malaysian peninsula.

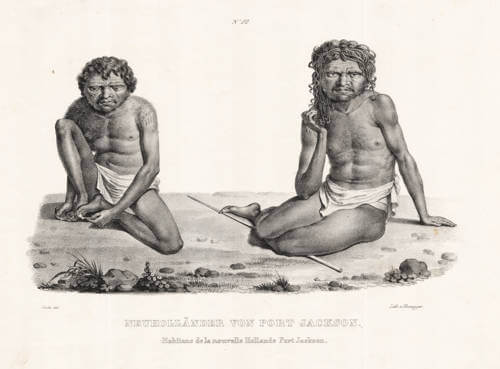

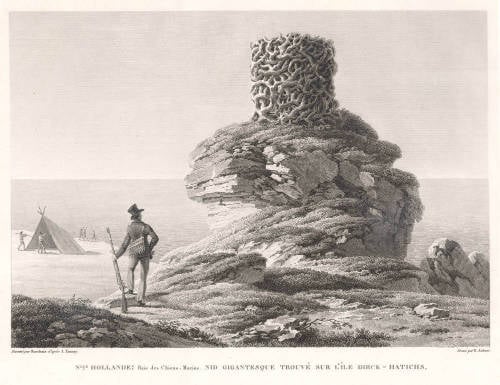

But most remarkable is the whole lower section of the chart that is filled with a majestic Austral-continent. The interior of this proto-continent is filled with images of trees, mountains, people and fabled animals. In addition, dozens of red city symbols all over the Southland suggests that we are dealing with a densely populated continent.

The UV images reveal beautifully dressed Southlanders, a gryphon (winged dragon) and other fabled animals. The Indian Ocean and Indonesian waters are embellished with decorative elements including compass roses, ships, sea monsters, and fish. Between Java and New Guinea a white mermaid with double tails can be discerned, very similar to the ones found on earlier maps of the sixteenth century like Munster's 1540 map of Asia.

In the Indian Ocean (Oceano Orientale) and on the left edge, large ships have been drawn in.

Additional multi-spectral imaging would reveal even more details, as has recently been demontrated with Yale's famous manuscript map on vellum of the world by Henricus Martellus Germanus and the techniques and results have been recently reported in detail by Chet van Duzer who proposed and initiated the project.

Source of the cartographic image

It had to be assumed that the artist who made this vellum chart was using a specific printed map of the world to start with. The quest for the cartographic source led to the large wall map of the world in twelve sheets (106 x 189 cm), engraved in 1600 by the Flemish cartographer Arnoldo di Arnoldi for publisher Matteo Florimi in Siena, only surviving in one example in the Niedersächsische Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek, Göttingen.

Arnoldo di Arnoldi in turn also copied his map from another source, namely Peter Plancius’ famous wall map of the world of 1592 (only known example in Colegio Corpus Cristi, Valencia).

He reduced and simplified Plancius’ wall map, omitting many text legends and details for lack of space.

Part of the remaining texts from Plancius were translated in Italian, and partly new Italian texts were added, like the description of Giava Maggiore, which has been copied on the manuscript vellum chart here.

For the depiction of the South Land, Arnoldo di Arnoldi follows Plancius’s wall map. South of the Indonesian Archipelago the regional toponyms of the kingdoms of Beach, Lucach and Maletur are located. These had been reported by Marco Polo and were introduced by Gerard Mercator on his famous wall map of the world of 1569, that would be the gold standard for the rest of the century. The painted map follows Arnoldo di Arnoldi’s shape of the Southland, while omitting a number of Mercator's toponyms. It does name the island of lesser Java, with Italian spelling Giaua minor.

The italian text legend on the Southland

A large Italian text is placed in the South Land, after Di Arnoldi, as follows:

L’Isola detta giava maggiore circonda tre mila migl [ia com:]

attesta Marco Paolo: soggetta al continuo impeto de

venti, come refer quell della Scala, gli habitatori

sono mori, e gentili tutti di piccola statura, corpo=

lenti, con la faccia larga, e per il piu vano nudi, eccecetto

che cuoprino le parti vergognose, sono superbi inhu [mani],

crudely, l’Isola abondante di specierie

The island of giava maggiore has a circumference of three thousand miles as

stated by Marco Polo: subjected to the continuous violence of

winds, as relates the one of the Scala, the inhabitants

are moors and pagans all short of stature, corpulent,

with broad face, and mostly they go naked, except

that they cover the shameful parts, they are arrogant, inhuman,

cruel, the island abounds in spices

La Scala is the neighbourhood in Venice where Marco Polo lived. The note about the three thousand miles circumference is found in several medieval sources, whereas the information on the inhabitants with broad faces comes from the Itinerario of Ludovico de Varthema, who is believed to be the first European to visit the Spice Islands in 1505. The Portuguese would only reach them in 1512.

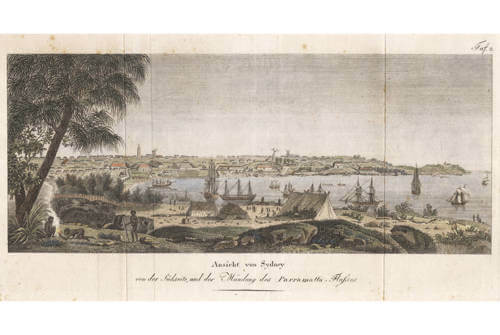

Purpose of an artist world map painted on vellum

Arnoldo de Arnoldi's wall map of the world in 12 sheets issued in Siena in 1600 was an attractively engraved work, but evidently not good enough to satisfy rich merchants and aristocrats. Instead of such commercially available ordinary printed works, they wanted to own unique trophy versions to impress and outshine others. They consigned skillful artists to produce manuscript versions on vellum, thus creating true works of art. The printed model was broadly followed, but embellished with artistic and decorative elements, to make them as attractive as possible.

The resulting charts on vellum were displayed as decoration and source of information on the walls of the patron's large mansions and palaces. The display of such pieces of art showed their visitors that they were involved in trade in all corners of the world, were knowledgeable of the most up-to-date geographical information and were Maecenas of arts.

For an impression of what such maps looked like in full glory, see the 1583 fresco paintings by Ignazio Danti that have survived in the famous Vatican Gallery of Maps.

Rarity

The image of the world obviously had to be consistent with the latest knowledge. Continuous discoveries and explorations resulted in rapid and frequent changes of the known image of the world.

In order to follow this cartographical progress as much as possible, owners would frequently replace obsolete wall maps with updated versions that reflected the latest changes. This is one of the reasons that wall maps of the world had a high mortality.

But there were additional factors in play. From the moment they were mounted and attached to rollers, wall maps were irrevocably doomed to perish sooner rather than later, they were destined to destruction, by exposure to the elements: sunlight, humidity, dampness, temperature fluctuations, smoke from pipes, smoke and soot from hearths, varnish, frequent touching, and so on. Made from live material they were also eaten by insects, worms and micro-organisms. They collapsed under their own weight or were torn by the weight of the wooden rollers. When darkened and colour-faded and outdated in contents, they were often disposed of, also because of their inconveniently large size. But even if they were moved to the archives of libraries, they were exposed to dust and rats and insects.

This also was the fate of this manuscript world map on vellum here. Only by a stroke of miraculous luck has a significant part of this cartographical document managed to survive the ravages of time. Only because of the valuable properties of vellum has our fragment survived the centuries, through a “second life” as a book binding, inside out.

Despite the condition, the chart must be regarded as an important witness of early Italian artistic cartography and as a unique document of the hypothetical pre-history of the fifth continent.

Literature:

Almagià, R. ‘Il planisfero di Arnoldo de Arnoldi (1600)’. In: Pubblicazioni dell’Istituto di Geografia dell R. Università di Roma. Serie B, Num. 2. Roma 1934.

Shirley, R. The Mapping of the World. London 1983.

Van der Heijden, H.A.M. ‘Wie was Arnoldo di Arnoldi?’. In: Caert-Thresoor, 18 (1999) no. 2, pp. 37-40.

Chet van Duzer, Henricus Martellus's World Map at Yale (c. 1491), 2019.

Related Categories

Related Items