Leen Helmink Antique Maps

The missing chart of the route

The item below has been sold, but if you enter your email address we will notify you in case we have another example that is not yet listed or as soon as we receive another example.

Stock number: 19018

Zoom ImageTitle

DESCRIPTIO HYDROGRAPHICA accommodata ad Battavorum navigationem in Javam insulam Indiæ Orientalis, factam; ad quam postridie Calendas Aprilis ann. 1595 ex Hollandia solverunt et ex qua domum redierunt 3. Idus Augusti an. 1597. Horum exitus reditusq3 via his notis ooo demonstratur. De hac navigatione extat descriptio lectu perquam admiranda

First Published

Amsterdam, 1598

This Edition

1598

Technique

Condition

excellent

Price

This Item is Sold

Description

Enter the Dutch

The dreams and labours of Petrus Plancius and Jan Huyghen van Linschoten culminated in the Dutch First Fleet to the Indies taking place from 1595 to 1597. It was instrumental in the opening up of the Indonesian spice trade to the merchants that would soon form the United Dutch East India Company (VOC). This famous pioneering voyage, commanded by Cornelis de Houtman, would abruptly end the Portuguese Empire ́s trade monopoly for the East and it would dramatically change the Indian Ocean theatre, notably the balance of power and the rules of trade. Right from this first voyage onward, the Dutch were going to dominate the East Indies and its trade for more than 350 years.

Rarity

Only copies known (all uncoloured):

* Amsterdam, Maritime Museum

* Rotterdam, Maritime Museum

* Verhoeff VOC Collection (The Netherlands)

Monumenta Cartographica Neerlandica, Vol VII, 2003

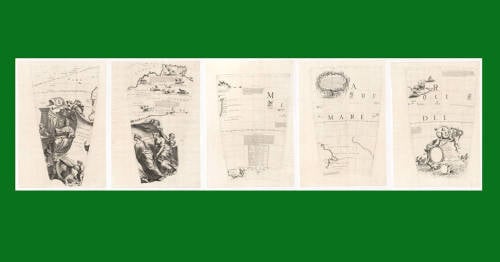

In 1915, Burger prepared a description of all maps known to him that Cornelis Claesz had published separately between 1591 and 1598. Burger suspected that Claesz had also published a large map pertaining to the first Dutch expedition to the Orient. He based his assumption on two facts. One piece of evidence was the small but highly instructive general map that appeared on the title page of Lodewijcksz's printed journal. Furthermore, Burger's suspicion was based on the fact that also Théodor de Bry, in the third volume of his Petits Voyages, included a map showing the entire route travelled by Cornelis de Houtman on that voyage. Thus, De Bry must have copied his map from an original one that had been published previously in Amsterdam. Burger's suspicion has been confirmed; three copies have been traced in the past 40 years.

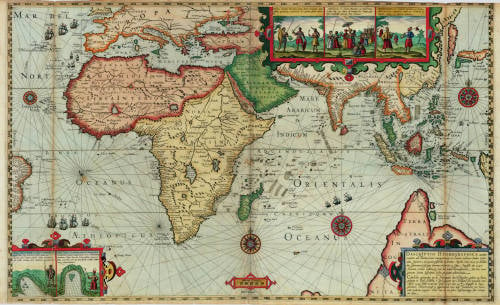

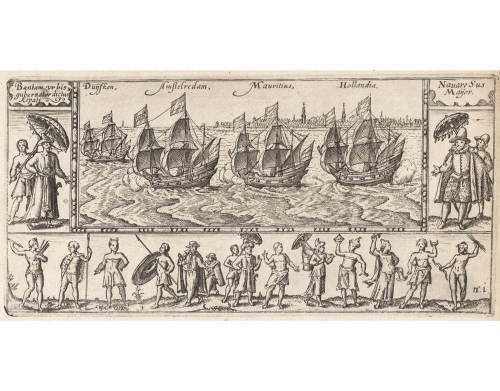

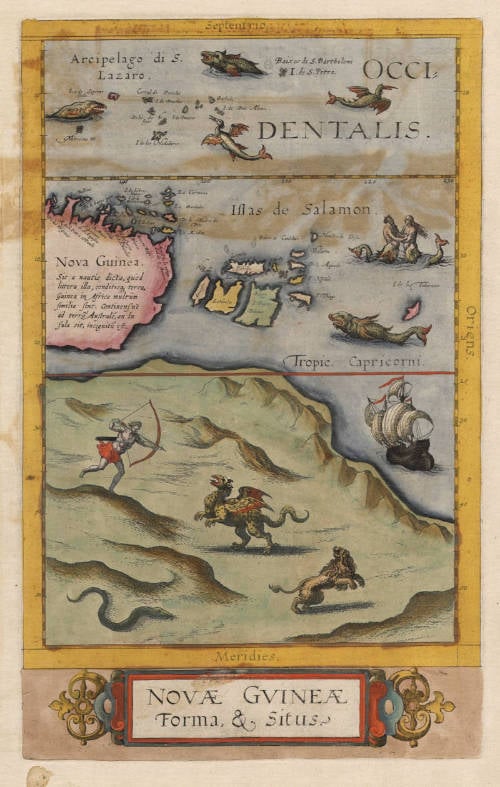

A scrollwork cartouche in the lower right corner contains the title of the map in Latin and Dutch. A scale bar in German miles is drawn in a simple cartouche running along the middle of the map's lower edge. As decorative elements, the map image includes various figures from the journal of Willem Lodewijcksz. A little map of Mossel Bay in Southern Africa and one of the Bay d’Antongil on Madagascar, are placed in the lower left corner. Both are accompanied by a text in Latin. A panel with three figures representing the inhabitants of Bantam and its surroundings is shown in the upper right corner. The series begins with a presentation of the soldiers, followed in the central piece by a depiction of their commander. Farmers are shown in the picture on the right side.

On both sides, a latitude scale is shown (55°N-54°S); midway of the map borders, the celestial directions are marked in Latin. Emanating from a central compass rose, compass lines are drawn to eight 16-pointed compass roses, four of which are completely filled in. The name of the engraver is not given, but in view of the strong similarity to the signed general map of the Second Voyage, the map is in all likelihood the work of Benjamin Wright.

The map shows the area between the easternmost point of Brazil in the west and the western point of New Guinea in the east. In the north, the map image reaches from Emden in Europe and Korea in Asia to the protuberance of a large TERRA AUSTRALIS INCOGNITA in the south. Contemporary material was used as source for the representations; this consisted mainly of maps that had recently been published by Cornelis Claesz. For instance, the coasts, islands, and shallows in the Indian Ocean were copied from the maps in Van Linschoten’s Itinerario (1596), while most of the Indonesian archipelago and the Philippines corresponds in terms of drawing and toponyms to Plancius's map of the Moluccan Spice Islands (1592). For the depiction of Korea and Japan, which were no longer included on Plancius's map, the model was Luis Teixeira's map of this area found in Ortelius's Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (1595). Plancius's hypothetical coastline of South Java has been left out. It is striking that not a single Dutch name appears anywhere on the map. Nor are there any names that are derived directly from De Houtman's voyage.

The main purpose of this general map was to depict the route of the first Dutch fleet to sail to the East Indies in 1595-97; a voyage which had received so much acclaim for its success. The entire route taken by Cornelis de Houtman is drawn on the map. Along the route heading toward the Orient (Exitus), four ships are depicted twice; on the homeward journey (Reditus), the three ships that remained are also depicted twice. The route they sailed is described extensively in the previous section of this chapter. This map was listed for sale in Cornelis Claesz's Const ende Caert-Register (1609) in the section under the heading ‘De Caerten van alle Navigatien'. There, together with the 50 plates taken from the journal, it is offered for the price of "26 stuivers" [pennies].

(Günter Schilder)

Cornelis de Houtman (1565-1599)

Cornelis de Houtman, born in 1565 in Gouda, the Netherlands, was a pivotal figure in the Age of Exploration. He is best remembered as the commander of the first Dutch fleet to the East Indies (modern-day Indonesia) from 1595 to 1597. This expedition marked the beginning of Dutch efforts to establish a foothold in the lucrative spice trade, ultimately leading to the rise of the Dutch East India Company (VOC).

Early Life and Context

Cornelis de Houtman grew up during a transformative period in European history. The late 16th century was marked by the struggle for independence of the Dutch Republic from Spain, as well as fierce competition among European powers for dominance in the spice trade. Portugal had established a monopoly over the trade routes to Asia, particularly to the East Indies, by the early 16th century. However, the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588 and growing dissatisfaction with Portuguese control spurred the Dutch to seek direct access to Asian markets.

De Houtman and his brother Frederick were merchants with connections to Amsterdam’s prominent trading community. In 1592, they were sent to Lisbon to gather intelligence about Portuguese trade routes to Asia. Their observations would later inform the plans for a Dutch voyage to the East Indies.

The First Voyage to the East Indies (1595–1597)

In 1595, Cornelis de Houtman was appointed to lead a fleet of four ships — Amsterdam, Hollandia, Mauritius, and Duyfken — in what became known as the "First Dutch Fleet." Sponsored by a consortium of Amsterdam merchants known as the Compagnie van Verre ("Company of Distant Lands"), the voyage was an ambitious but perilous endeavor.

The fleet departed from Texel in April 1595, with approximately 250 crew members. The voyage was plagued by challenges, including inadequate navigation charts, harsh weather, scurvy, and conflicts among the crew. Despite these difficulties, the expedition reached the Sunda Strait (between Sumatra and Java) in June 1596. They established contact with the Sultanate of Banten, a major hub for the spice trade.

Relations with the local rulers quickly soured due to de Houtman's abrasive behavior and lack of diplomatic finesse. Hostilities broke out, forcing the fleet to leave Banten without securing a trade agreement. The fleet also explored Madura and Bali, where they managed to acquire a modest cargo of spices, including pepper.

The return journey to the Netherlands was equally arduous. Disease and hunger took a severe toll on the crew, with only 87 of the original 250 surviving the voyage. Despite its challenges, the expedition proved that it was possible for Dutch ships to reach the East Indies and return with valuable goods.

Legacy and Impact

Although the expedition was not an immediate financial success, it was a landmark achievement in Dutch maritime history. It demonstrated that the Portuguese monopoly on the spice trade could be challenged and paved the way for subsequent Dutch expeditions. Cornelis de Houtman became a symbol of Dutch ambition and resilience, even as his leadership style drew criticism for its harshness and lack of diplomacy.

The information gathered during the voyage laid the groundwork for future expeditions. Within a few years, the Dutch would establish more permanent trade routes and trading posts in the East Indies. In 1602, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) was founded, becoming a dominant force in global trade for the next two centuries.

Final Years and Death

Cornelis de Houtman did not live to see the full fruits of his pioneering efforts. In 1599, he joined another expedition to the East Indies, this time under the command of his brother Frederick. While in Aceh (northern Sumatra), de Houtman became embroiled in a violent conflict with the Sultan of Aceh. He was killed during a skirmish, ending his tumultuous career.

Conclusion

Cornelis de Houtman's first voyage to the East Indies was a milestone in the Dutch Republic’s rise as a global maritime power. His determination and leadership, despite their flaws, opened new horizons for Dutch traders and helped usher in an era of prosperity and dominance in the spice trade. Today, de Houtman is remembered as a trailblazer whose efforts marked the beginning of the Dutch Golden Age.

Benjamin Wright (1575-1613)

London, Amsterdam, Bologna and Rome.

Engraver and copperplate printer. Engraved a pair of celestial and terrestrial charts to illustrate John Blagrave, “Astrolabium uranicum generale" 1596;

Beschrijvinghe der zeecusten van Barbarielal tusken de straet van Gijbraltar ende caep de Cantin for Lucas Jansz. Waghenaer, “Thresoor der zee-vaert" 1596;

maps of Java, Sumatra, Madagascar and St. Helena for “Caert-thresoor, inhoudende de taflen des gantsche werelts landen” 1599, published by Cornelis Claesz of Amsterdam;

Gabriel Tatton, Nova et rece terraum et regnorum Californiae, Novae Hispaiae Californiae. Novae Hispaiae, Mexicanae, et Peruviae 1600;

Gabriel Tatton, Maris Pacifici quod Mar del Zur 1600; Hispaniae nova describtio 1600; Tabula geographica provinciarum Brabantiæ, Geldriæ comitatus, Sutphaniæ, Traiectini, Transilvaniæ, Drentiæ, Twentiæ, Hollandiæ, et Frisiæ; una cum præterlabentium fluviorum delineation 1600. for Cornelis Claesz;

Waerachtige af conterfeytinge der vermaẽr riviere van Londen, anders genaempt die Tamesis for Lucas Jansz. Waghenaer,

“Thresorie ou cabinet de la route marinesque" 1601;

Beschrijvinghe der landen ende zee-custen van Eembderlandt and eleven other charts for Lucas Jansz. Waghenaer, "Thresoor der zeevaert" 1602;

fourteen charts for Lucas Jansz. Waghenaer, "Den groten dobbelden nieuwen spieghel der zeevaert" 1603, again for Claesz;

a further thirty maps of the same size and style, including Alata castra Scotia regia urbs et metrolis vulgó Edimburgum ca. 1603 and Topographia insulæ Huenæ in celebri porthmo regna Daniæ were evidently engraved for Claesz at this time, but are extant only in Claes Jansz. Visscher, “Tabularum geographicarum contractarum libri quatuor denuo recogniti" 1649;

Italia nuova da Gio Antonio Magini 1608;

eleven maps for Magini's “Italia data in luce” 1620, the maps engraved somewhat earlier;

seven maps for Johann Isaac Pontanus, “Rerum et urbis Amstelodamensium historia” 1611, for Jodocus Hondius 1, again engraved at an earlier date, etc.

Said to have been born in 1575, and perhaps to be identified with the Benjamin Wright made free of the Goldsmiths' Company by patrimony 17 Mar 1597. Heawood suggested that the map Florentissimoru[m] Enorum Angliæ et Hiberniæ accurata descriptio veteribus et recentioribus nominibus illustrata 1594 might be by Wright, but Wright himself referred to his The armes of all the cheif corporations of England 1596 as the "first fruit of his labours”. He was working in Amsterdam by 1602 and probably for some years earlier, referred to in that year as an "Engelsch plaetsnyder woonende tot Amstelredam" [English copperplate cutter living in Amsterdam]. He subsequently worked in Bologna 1607-1608 and later Rome for the Italian publisher Giovanni Antonio Magini, who must have greatly valued Wright's work to have borne with so tiresome a collaborator, irregular in life and given to drink, for twice he had to release plates which Wright had pawned in Rome. Though other engravers known to have worked on Magini's “Atlas” ... it is surprising that no plates are signed but those bearing Wright's name” (Hind). John Evelyn bracketed Wright with Thomas Cecill as "little inferior to any we have enumerated for the excellency of their burins and their happy design”.

At the Hartshorne in Paternoster Row 1596, Amsterdam 1602, Bologna 1607-1608, Rome 1608-1613.

BBTI, BM. Burden (1996). COPAC. Goldsmiths. Griffiths. GL. Hind. Koeman. Shirley (2001). STC. Taylor (1954). Tooley.

(Worms and Baynton Williams)

Literature:

Laurence Worms and Ashley Baynton Williams, British Map Engravers, London, Rare Book Society, 2011, pp 735-736.

Valerie Scott, Tooley's Dictioonary of Mapmakers - Revised Edition Q-Z, Early World Press, 2004.

A.M. Hind, Engraving in England in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. I, The Tudor Period, Cambridge University Press, 1952, pp 212-213.

Related Categories

Antique maps of the World

Antique maps of the East India Company

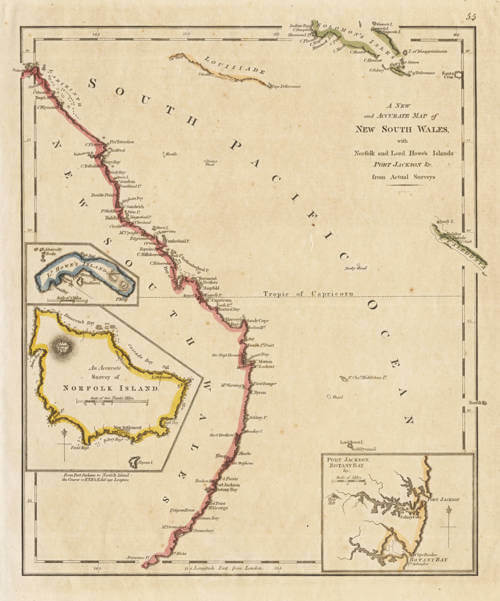

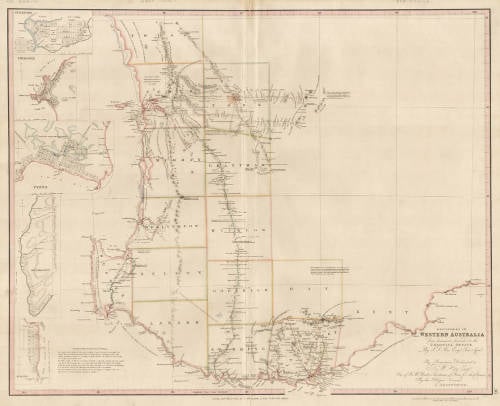

Antique maps of Australia

Antique maps of Japan

Antique maps of China

Antique maps of the Philippines

Antique maps of Southeast Asia

Antique maps of India and Ceylon

Antique maps of Korea

Antique maps of the Middle East

Antique maps of Asia

Antique maps of Africa

Old books, maps and prints by Cornelis de Houtman

Old books, maps and prints by Benjamin Wright