Leen Helmink Antique Maps

Antique map of Paris by Münster

The item below has been sold, but if you enter your email address we will notify you in case we have another example that is not yet listed or as soon as we receive another example.

Stock number: 18864

Zoom ImageDescription

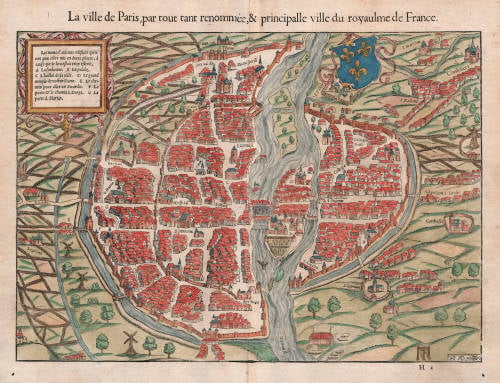

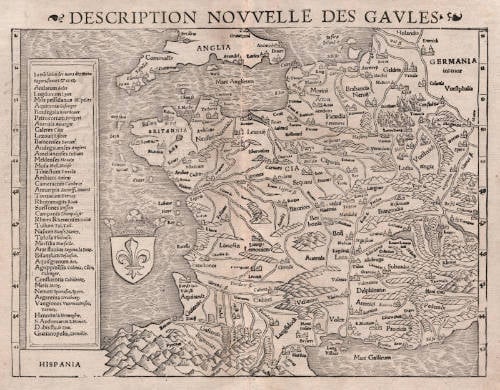

Splendid woodcut engraving of the city of Paris, that was published in Basle by Sebastian Münster in his 'Cosmographia' in 1550.

This map is the oldest printed map of Paris, pre-dating by 22 years the famous 1572 Braun & Hogenberg plan of Paris, which is an updated copy of this Münster map.

In antiquity, the city was the capital of the Gallic tribe of the Parisii, and when conquered by the Romans under Julius Caesar it was named Lutetia. Already in antiquity it was an important city for merchants, who used the Rhone-Seine rivers as standard route from Marseille to England and back.

The oldest parts of the city and the original Gallic and Roman stronghold were located on the big island in the river, still known today as "Ile de la Cité" (Isle of the City). The bridges over crossing Seine River are lined with shops.

In the upper right, the Royal fleur-de-lis coat-of-arms of France is shown.

The upper left has an index of placenames.

The city is shown in bird eye's view looking from the west. North is at the left of the map, so the Seine River ("Saquana") flows from the top (east) to the bottom (west) of the map.

The map shows the city just after the Middle Ages, with the first Renaissance city wall extensions on the North side of the city (left in the map, note that the original inner medieval walls are still present). The city walls are surrounded by a moat

In the centre of the map is Isle de la Cité, with the Cathedral of Notre Dame shown prominently at the upper end (index D: "Le grand temple de nostre Dame.").

In the lower end of the island is the old Royal Palace (index B: "Le Palaiz."), at the location of todays Palace de Justice. The island(s) above it (now Ile St Louis) are not yet inhabited.

To the right (south) of Ile de la Cité, in today's Quartier Latin, is the "Collegia" and "Collegium Regio", the oldest University in the world, still present at the same location (index A: "La sorbonne.").

To the left is the City Hall, where it still is today (index C: "L'hostel de ville.").

At the bottom of the map, between the Medieval and the new 16th century city gates to the left of the river, at the location of today's Louvre museum, is the Royal castle of the French monarchs ("Arx Regis)".

At the top of the map, left of the river, is the fortress and prison of the Bastille ("Arx valida"). Other city gates are named and still carry these names today, for instance at the left

- index E: "Le chemin pour aller en Picardie",

- index F: "La porte et le chemin S.Denys." (St. Denis),

- index G: "La porte S.Martin".

Many churches and monasteries with familiar names are shown and indicated. Some outside the city walls in those days, are now of course well inside the city. In the lower right we see "S.German [des Pres]", At the right we see "S.Victor", "S.Medart", "S.Marceau". At the left "S.Loren". To the right "Suburbium S.Iacobi".

In the lower right and in the center left of the map, just outside the city, are multiple gallows with hanged convicts, emphasizing to visitors that this was a city of law and order.

Sebastian Münster (1489-1552)

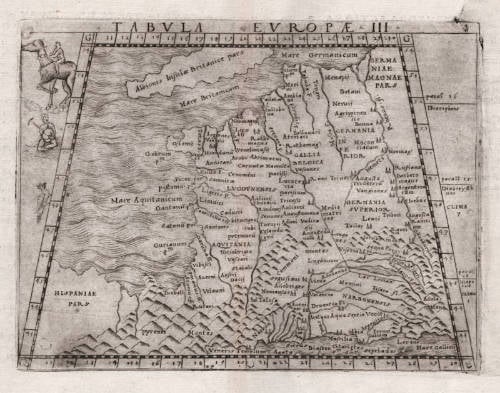

Following the various editions of Waldseemüller's maps, the names of three cartographers dominate the sixteenth century: Mercator, Ortelius and Münster, and of these three Münster probably had the widest influence in spreading geographical knowledge throughout Europe in the middle years of the century.

His Cosmographia, issued in 1544, contained not only the latest maps and views of many well-known cities, but included an encyclopaedic amount of detail about the known - and unknown - world and undoubtedly must have been one of the most widely read books of its time, going through nearly forty editions in six languages.

An eminent German mathematician and linguist, Münster became Professor of Hebrew at Heidelberg and later at Basle, where he settled in 1529. In 1528, following his first mapping of Germany, he appealed to German scholars to send him "descriptions, so that all Germany with its villages, towns, trades, etc. may be seen as in a mirror", even going so far as to give instructions on how they should "map" their own localities. The response was far greater than expected and such information was sent by foreigners as well as Germans so that, eventually, he was able to include many up-to-date, if not very accurate, maps in his atlases.

He was the first to provide a separate map of each of the four known Continents and the first separately printed map of England. His maps, printed from woodblocks, are now greatly valued by collectors. His two major works, the Geographia and the Cosmographia were published in Basle by his step-son, Henri Petri, who continued to issue many editions after Münster's death of the plague in 1552.

(Moreland & Bannister).

The remaining modern maps, [...], are all drawn on a plane projection, undergraduated, without scales, and variously oriented with north, south, east or west at the top, "without the excuse of topographical necessity", as Nordenskjöld severely remarks. In spite of these and other cartographic defects, they constitute an important corpus of geographical knowledge and interpretation; Münster was the first atlas-maker to furnish separate maps of the four continents then known; and for England, Scandinavia and southern Germany, eastern Europe and America he brought recent and significant representations into general currency.

(Skelton).

The Cosmographia of Sebastian Münster must rank as the greatest geographical compendium of the period - an immensely detailed work illustrated with woodcut portraits, scenes, town plans and panoramas, and maps. Born in 1488, Münster was a Fransiscan who became Professor of Hebrew at Heidelberg and later at Basle, where he taught Hebrew and, amongst other works, published the first German translation of the Bible from Hebrew. In 1540 his edition of Ptolemy's Geographia was published, followed in 1544 by the Cosmographia Universalis. Together these ran to over 35 editions published mostly in Basle in Latin, German, French and Italian versions. Münster's particular cartographic importance lies in the number of 'new' maps he introduced and, above all, in the innovative, separate mapping of each of the four continents. The map of the Americas is not only the first map to show the Western Hemisphere separately, but is also the first to show North and South America joined together.

(Potter p38).

Sebastian Münster was raised as a Franciscan monk, converted to Lutheranism, taught Hebrew at Heidelberg and Basle, and was proficient in Greek and some Asian tongues. He died of the plague in 1552. First published in 1540, his atlas was the first to contain separate maps of each of the four continents.

(Suárez).

In 1540 Sebastian Münster, who was to become one of the most influential cartographers in the sixteenth century, published his edition of Ptolemy's Geographia with a further section of modern, more up-to-date maps. He included for the first time a set of continental maps, the America was the earliest of any note. Münster studied Hebrew at Heidelberg and was a scholar of geography, writing amongst other works the Polyhistor.

He was one of the first to create space in the woodblock for the insertion of place-names in metal type. The map's inclusion in Münster's Cosmography, first published in 1544, sealed the fate of "America" as the name for the New World. The book proved to be very popular, there being nearly forty editions during the following 100 years.

(Burden).