Leen Helmink Antique Maps

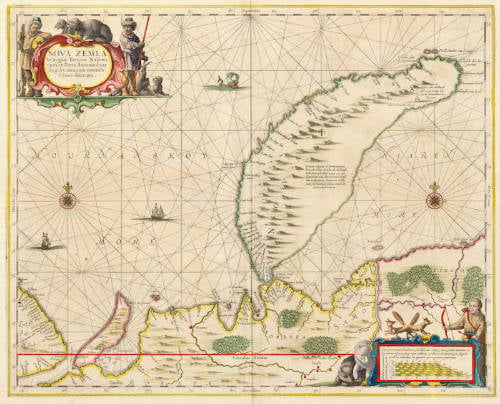

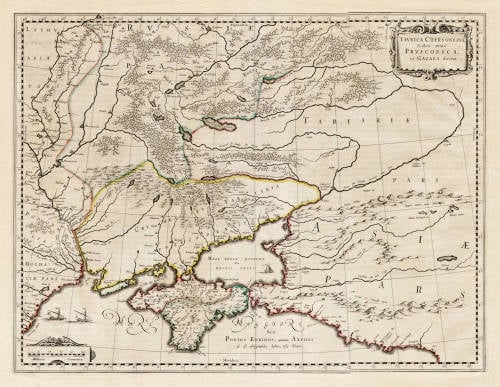

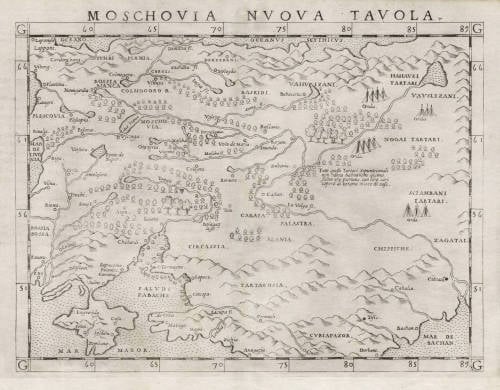

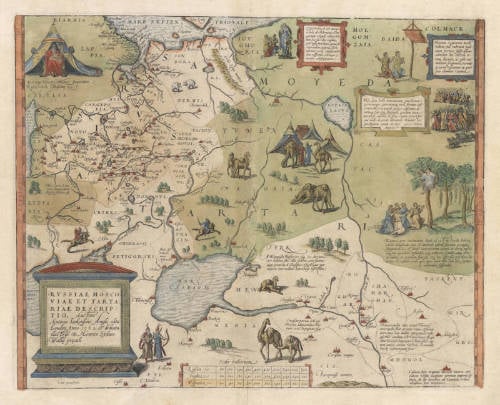

Antique map of Russia by Ulm Ptolemy

Stock number: 18756

Zoom ImageTitle

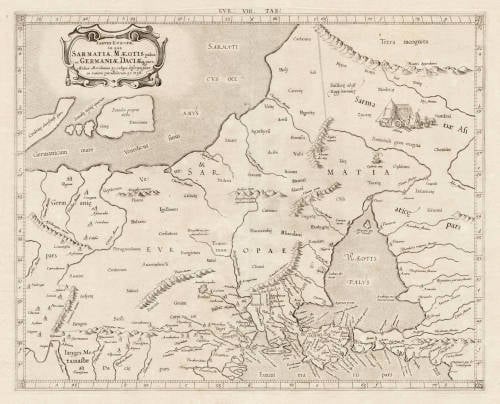

Tabula Octava

First Published

Ulm, 1482

This Edition

1486

Size

38.0 x 55.5 cms

Technique

Condition

excellent

Price

$ 12,500.00

(Convert price to other currencies)

Description

Nicolaus Germanus' spectacular version of Ptolemy's eight map of Europe, covering today's Russia, Ukraine, Eastern Europe and Scandinavia. Very rare.

From the second 1486 edition of the celebrated Ulm Ptolemy atlas of 1482, which was the first atlas printed outside Italy and the first atlas illustrated with woodcut maps.

This example in beautiful original color from the publisher. Pristine condition. A strong and even impression of the woodblock. Collector's example.

"This striking map depicts Russia and Eastern Europe as envisaged by the second century A.D, cartographer Claudius Ptolemaeus, and is one of the earliest obtainable printed maps of the area. The map extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Crimea and the Black Sea. To the west is the Vistula river ("istula fluvius"), with a distended Azov Sea in the east. The majority of the map is marked "Sarmatia Europe" - the Sarmatian kingdom ruled a great swathe of central Asia between the fifth century BC and the fourth century AD. At its highly around the first century B.C. the empire stretched to the banks of the river Vistula.

(Daniel Crouch Rare Books)

Lienhart Holle / Nicolaus Germanus

"As far as cartography is concerned the printing of Ptolemy's Geographia at Ulm in 1482 (and 1486) - the first edition with woodcut maps - was an event of the greatest importance.

The edition of Ptolemy's Geographia printed at Ulm in 1482 was the first published outside Italy and the first with woodcut map; it contained 26 maps based on Ptolemy and six 'modern' maps"

(Moreland & Bannister)

"The first edition printed north of the Alps, and the first woodcut version, is more crudely executed than the previous (Ptolemy) productions. Nevertheless the bold Germanic style and the Gothic lettering have a distinctive decorative appeal, especially when combined with rich colouring. The printer was Leinhart Holle, also known for the publication of the illustrated book Buch der Weisheit.

Shortly after the publication Leinhart Holle went bankrupt. His stock was taken iover by Johann Reger who, four years later in 1486, put out a second printing of about 1000 copies. Within and between both editions variations occur in respect of the text and printed legends although the same basic blocks were used."

(Shirley)

"In 1482 Lienhart Holle in Ulm published a revised edition of Ptolemy's Geographia with the reworking of the Ptolemaic corpus by the cartographer Nicolaus Germanus Donis. The atlas included five additional "modern" maps: Italy, Spain, France, Scandinavia, and the Holy Land. The atlas would be the first book printed by Lienhart Holle, however, it would appear that the venture proved ruinously expensive and his business would go bankrupt shortly after publication. The remaining sheets, the woodblocks and the types passed to Johann Reger in Ulm, who reissued the work in 1486.

As well as the modern maps the atlas bears some other notable first. It was the first time that maps were signed by the artist responsible for the woodcutting; in this case Johannes of Armsheim, who signed the world map, and incorporated a backwards N into the woodcut text on each map. It is also the first to print the accompanying text on the verso of the map to which it refers."

(Skelton)

Claudius Ptolemy (c.100 - c.170)

Ptolemy, Latin in full Claudius Ptolemaeus was an Egyptian astronomer, mathematician, and geographer of Greek descent who flourished in Alexandria during the 2nd century AD. In several fields his writings represent the culminating achievement of Greco-Roman science, particularly his geocentric (Earth-centred) model of the universe now known as the Ptolemaic system.

Virtually nothing is known about Ptolemy’s life except what can be inferred from his writings. His first major astronomical work, the Almagest, was completed about 150 ce and contains reports of astronomical observations that Ptolemy had made over the preceding quarter of a century. The size and content of his subsequent literary production suggests that he lived until about 170 AD.

Astronomer

The book that is now known as the Almagest (from a hybrid of Arabic and Greek, “the greatest”) was called by Ptolemy Hē mathēmatikē syntaxis (“The Mathematical Collection”) because he believed that its subject, the motions of the heavenly bodies, could be explained in mathematical terms.

Mathematician

Ptolemy has a prominent place in the history of mathematics primarily because of the mathematical methods he applied to astronomical problems. His contributions to trigonometry are especially important. For instance, Ptolemy’s table of the lengths of chords in a circle is the earliest surviving table of a trigonometric function. He also applied fundamental theorems in spherical trigonometry (apparently discovered half a century earlier by Menelaus of Alexandria) to the solution of many basic astronomical problems.

Among Ptolemy’s earliest treatises, the Harmonics investigated musical theory while steering a middle course between an extreme empiricism and the mystical arithmetical speculations associated with Pythagoreanism. Ptolemy’s discussion of the roles of reason and the senses in acquiring scientific knowledge have bearing beyond music theory.

Geographer

Ptolemy’s fame as a geographer is hardly less than his fame as an astronomer. Geōgraphikē hyphēgēsis (Guide to Geography) provided all the information and techniques required to draw maps of the portion of the world known by Ptolemy’s contemporaries. By his own admission, Ptolemy did not attempt to collect and sift all the geographical data on which his maps were based. Instead, he based them on the maps and writings of Marinus of Tyre (c. 100 ce), only selectively introducing more current information, chiefly concerning the Asian and African coasts of the Indian Ocean. Nothing would be known about Marinus if Ptolemy had not preserved the substance of his cartographical work.

Ptolemy’s most important geographical innovation was to record longitudes and latitudes in degrees for roughly 8,000 locations on his world map, making it possible to make an exact duplicate of his map. Hence, we possess a clear and detailed image of the inhabited world as it was known to a resident of the Roman Empire at its height—a world that extended from the Shetland Islands in the north to the sources of the Nile in the south, from the Canary Islands in the west to China and Southeast Asia in the east. Ptolemy’s map is seriously distorted in size and orientation compared with modern maps, a reflection of the incomplete and inaccurate descriptions of road systems and trade routes at his disposal.

Ptolemy also devised two ways of drawing a grid of lines on a flat map to represent the circles of latitude and longitude on the globe. His grid gives a visual impression of Earth’s spherical surface and also, to a limited extent, preserves the proportionality of distances. The more sophisticated of these map projections, using circular arcs to represent both parallels and meridians, anticipated later area-preserving projections. Ptolemy’s geographical work was almost unknown in Europe until about 1300, when Byzantine scholars began producing many manuscript copies, several of them illustrated with expert reconstructions of Ptolemy’s maps. The Italian Jacopo d’Angelo translated the work into Latin in 1406. The numerous Latin manuscripts and early print editions of Ptolemy’s Guide to Geography, most of them accompanied by maps, attest to the profound impression this work made upon its rediscovery by Renaissance humanists.

(Britannica)

Related Categories

Related Items