Leen Helmink Antique Maps

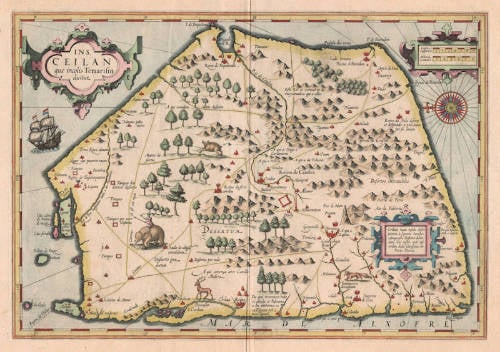

Antique map of Ceylon by Jodocus Hondius

Stock number: 18753

Zoom ImageTitle

Ins. Ceilan quae incolis Tenarisin dicitur

First Published

Amsterdam, 1606

This Edition

1606 or later

Size

34 x 50 cms

Technique

Condition

mint

Price

$ 1,250.00

(Convert price to other currencies)

Description

Jodocus Hondius' superb map of the island of Ceylon, first issued in the 1606 Mercator-Hondius series of atlases. As mentioned in the lower right cartouche, the map was designed by Petrus Plancius. The toponyms leave no doubt that the map is based on Portuguese sources. North is to the left of the map.

The map is the original copperplate that was engraved by Jodocus Hondius the Elder for inclusion in the Mercator-Hondius series of atlases, first published in 1606.

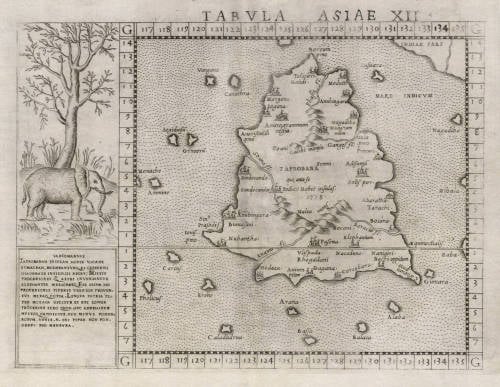

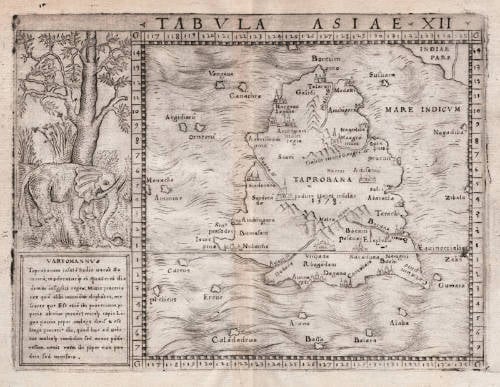

For reasons unknown, in 1638 the map was replaced by a re-engraved copperplate that is similar far less decorative and less skillfully executed, under publishers Johannes Jansson and Henricus Hondius.

van der Krogt 8380.1A:1.

Jodocus Hondius (1563-1612)

Jodocus Hondius the Younger (son) (1594-1629)

Henricus Hondius (son) (1597-1651)

Jodocus Hondius the Elder, one of the most notable engravers of his time, is known for his work in association with many of the cartographers and publishers prominent at the end of the sixteenth and the beginning of the seventeenth century.

A native of Flanders, he grew up in Ghent, apprenticed as an instrument and globe maker and map engraver. In 1584, to escape the religious troubles sweeping the Low Countries at that time, he fled to London where he spent some years before finally settling in Amsterdam about 1593. In the London period he came into contact with the leading scientists and geographers of the day and engraved maps in The Mariner's Mirrour, the English edition of Waghenaer's Sea Atlas, as well as others with Pieter van den Keere, his brother-in-law. No doubt his temporary exile in London stood him in good stead, earning him an international reputation, for it could have been no accident that Speed chose Hondius to engrave the plates for the maps in The Theatre of the Empire of Great Britaine in the years between 1605 and 1610.

In 1604 Hondius bought the plates of Mercator's Atlas which, in spite of its excellence, had not competed successfully with the continuing demand for the Ortelius Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. To meet this competition Hondius added about 40 maps to Mercator's original number and from 1606 published enlarged editions in many languages, still under Mercator's name but with his own name as publisher. These atlases have become known as the Mercator/ Hondius series. The following year the maps were re-engraved in miniature form and issued as a pocket Atlas Minor.

After the death of Jodocus Hondius the Elder in 1612, work on the two atlases, folio and miniature, was carried on by his widow and sons, Jodocus II and Henricus, and eventually in conjunction with Jan Jansson in Amsterdam. In all, from 1606 onwards, nearly 50 editions with increasing numbers of maps with texts in the main European languages were printed.

(Moreland and Bannister)

Petrus Plancius (1552-1622)

Born as Peter Platevoet in Flanders, Petrus Plancius studied abroad and became a theologian and a mapmaker.

He produced some globes and maps, including a well-known world map in 1592. He had a great influence on the Dutch Asian expeditions.

Early Years

Peter Platevoet was born in 1552 in the Flanders village of Dranouter. Little is known about his childhood, but it seems that his parents became Protestants. Platevoet studied theology, history, and languages in Germany and England. In England he probably learned about mathematics, astronomy, and geography. When he was older, Platevoet Latinized his name, as was the custom among savants at that time.

In 1576 he became a preacher in West-Flanders, a province in Belgium, and later that year he went to Mechelen, Brussels, and Louvain. In the 1580s he stayed in Brussels for a long time, but when the city surrendered to the duke of Parma, King Philip II of Spain’s governor-general in the Netherlands, in 1585 Petrus Plancius fled to the north. He lived in Amsterdam and became a pastor of the Dutch Reformed Church. From December 1585 until his death on 15 May 1622, he fulfilled his job as preacher. Plancius was a fervent Contra-Remonstrant and discussed many theological issues.

In addition to his thorough knowledge of the Holy Bible, he was well-grounded in the study of cosmography, geography, and cartography. He was not only one of the most talked-about preachers in the Dutch republic, but also one of the important mapmakers of his time.

Early Publications

Petrus Plancius was the first caert-snyder (map cutter) in the Dutch republic to produce waxed grid maps. Therefore, on 12 September 1594 he received a patent for the publication and distribution of the world map for twelve years from the States-General. He was, together with the Flemish engraver and map-maker Jodocus Hondius and the brothers Van Langren, one of the first makers of celestial globes in the Netherlands. His first globe was produced in 1589, a revision of an earlier celestial globe. Among his revisions were four additions to the southern sky: the two Magellanic Clouds (they were unnamed on the globe) and two new constellations, Crux and Triangulus Antarticus. Their positions were taken from reports of explorers.

In 1590 Petrus Plancius made five terrestrial maps for a Dutch edition of the Holy Bible. Two years later he made a well-known world map: Nova et exacta terrarum orbis tabula geographica ac hydrographica (New and exact geographical and hydrographical map of the world). This map contained celestial planispheres in the upper corners on which he added two additional constellations.

Asian Expeditions

Petrus Plancius was one of the driving forces behind the first Dutch expeditions to Asia, assisting with preparations and providing instruction. To avoid encounters with Spain and Portugal, which were already sailing to the East Indies around southern Africa, Plancius decided to try a northeast route around Asia. He supplied maps for the voyage and advised the fleet commander, Willem Barents, in celestial navigation. The northeast voyages of 1594 and 1595 were failures, but a third attempt was made in 1596. It was on that last expedition that Barents’s ship got stuck in the polar ice, and the crew had to spend the winter in Nova Zembla, an island northwest above Russia, in what came to be called the Barents Sea. Late in the spring of the next year, the crew was able to sail south in two small boats. Barents died on the return voyage; the survivors arrived at Amsterdam in November 1597, not having found a northeast passageway.

In 1595, together with Barents, Plancius published a book titled Nieuwe Beschrijvinghe ende Caertboeck van de Middelandtsche Zee (New description and map book of the Mediterranean Sea). In this work he designed a map that was engraved by the well-known globe- and map-maker Hondius.

Because the northeast sea route around Asia did not seem very promising, even before the third voyage a group of Dutch merchants had financed a southern expedition. Plancius again helped with the planning and used the opportunity to conduct scientific research. A theory in the late sixteenth century claimed that a compass needle’s variation from north (its declination) would enable one to determine longitude. Plancius developed his own theory to ascertain longitude at sea by means of magnetic variation. To test that theory during the southern voyage, Plancius taught junior merchant Frederik de Houtman how to measure and record compass declinations. It is known that the method developed by Plancius was used from 1596 onward by mariners.

Plancius also used the voyage to discover southern stars that were not visible from Europe. He taught navigators, especially Pieter Dircksz Keyser, but also other sailors, how to measure star positions with an astrolabe and instructed them to chart the southern sky. From ship records of 1596 it is known that the astrolabe was used to measure the declination of the southern stars.

The Dutch southern expedition, known as the Eerste Shipvaart, or First Voyage, set sail from the port of Texel in April 1595. It reached the East Indies in 1596 and returned to Texel in August 1597. Plancius asked Keyser, the chief pilot on the Hollandia, to make observations to fill in the blank area around the south celestial pole on European maps of the southern sky. Keyser died in Java the following year, but his catalog included 135 new stars arranged in twelve new constellations. Most of them were invented to honor discoveries by sixteenth-century explorers. They were first published on a 1598 celestial globe made by Hondius.

After the foundation of the VOC (Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, or East India Company) in 1602, Plancius became its first mapmaker. During the first quarter of the seventeenth century, he seemed more interested in preaching than in cartography and cosmography. But still, some of his maps were published during that time. In 1607 he produced a large revised world map. In 1612 he created a celestial globe, and later he designed an Earth and another celestial globe (1614 and 1615), both brought out by the well-known publisher Petrus Kaerius. His contemporaries described him as one of the greatest geographers of his time.

Bibliography

A complete bibliography of Plancius’s work, with descriptions of much of his maps and publications, is Günter Schilder, Monumenta Cartographica Neerlandica, Vol. VII, Cornelis Claesz (c. 1551–1609): Stimulator and Driving Force of Dutch Cartography, Alphen aan den Rijn, Netherlands: Canaletto/Repro-Holland, 2003.

(encyclopedia.com)