Leen Helmink Antique Maps & Atlases

www.helmink.com

Schedel

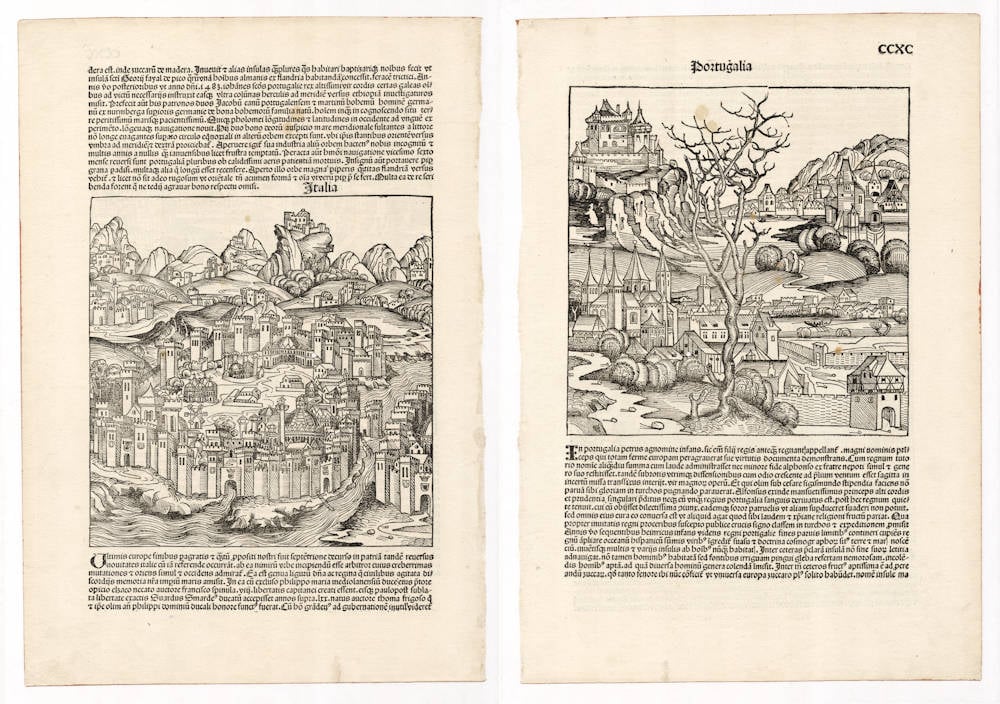

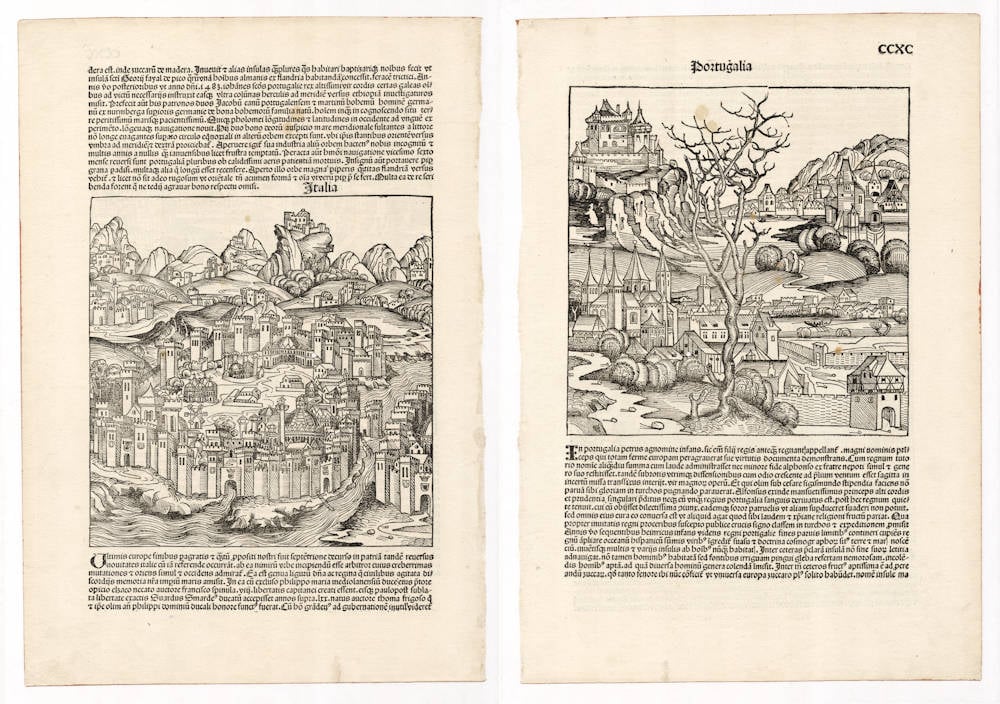

Italia / Portugalia

Certificate of Authentication and Description

This is to certify that the item illustrated and described below is a genuine antique

map, print or book that was first produced and published in 1493, today 532 years ago.

April 17, 2025

Cartographer(s)

Schedel

First Published

Nuremberg, 1493

This edition

Size

23.5 x 22.4 cms

Technique

Woodcut

Stock number

19205

Condition

excellent

Description

Very early woodcut by Hartmann Schedel to focus on Italy and Portugal in the form of a medieval town. This is one sheet, with Italy on one side, and Portugal on the other.

"The renowned Nuremberg Chronicle is one of the great books of the Renaissance."

(Potter).

"The Nuremberg Chronicle, as this compendium is popularly known, was one of the most remarkable books of its time. The text is an amalgam of legend, fancy, and tradition interspersed with the occasional scientific fact or authentic piece of modern learning. The many illustrations include two maps - one map of the world and one of Northern Europe - together with views of the principal cities, and a host of repeated decorative woodcuts. Hartmann Schedel, a physician of Nuremberg, was the editor-in-chief; the printer was Anton Koberger, and among the designers the most famous were Michael Wohlgemut and Hanns Pleydenwurff, masters of the Nuremberg workshop where Albrecht Dürer served his apprenticeship.

The first edition of the Nuremberg Chronicle in July 1493 was in Latin and there was a reprint with German text in December of the same year."

(Shirley).

Condition

The desirable first edition, with Latin text. Wonderful incunabula printed text with hand drawn red rubrifications. Strong and even imprint of the woodblock. Thick paper, no restorations. Pristine collector's condition.

Hartmann Schedel and the Nuremberg Chronicle

One of the most fascinating printed books from the fifteenth century is Hartmann Schedel's Liber Chronicarum or, as it is widely known to an English-speaking audience today, the Nuremberg Chronicle. The Chronicle was published in two editions in the same year, first a Latin edition, published on July 12th 1493, and then a German edition, published on December 23rd 1493.

The Chronicle is the most ambitious and impressive example of book publishing from the fifteenth century. A folio volume, with (in the German edition), 286 pages of text, the Chronicle contains somewhere in the region of 1,800 woodcuts (many duplicates), designed to present a textual and pictorial history of the world, from the Creation to the fifteenth century, dawn from Biblic sources, supplemented from classical authors such as Pomponius Mela, Gaius Julius Solinus.

The principal illustrations are maps of the World and of Germany and central Europe, but there are also 99 views of towns and cities, several anonymous, principally of Europe, but including some from the Near East, such as Constantinople, Damascus, Babylon and Jerusalem. The majority of these views are imaginary. Thus, for example, the woodcut entitled Anglia, and variously said to be London or Dover, is more plausibly a view of Nuremberg. Indeed, 49 of the views are actually printed from a group of 14 woodcuts, used indiscriminately throughout. There are also thirty double-page view of cities, including Nuremberg, Venice, Rome, Strasbourg, Saltzburg, Ulm, Basle and others, where the publishers have attempted to portray a more realistic image of the city shown.

In addition to the topographical images, there is an enormous number of other subjects, including diagrams of the Creation, family trees, portraits & biblical scenes. It is a veritable pictorial encyclopaedia both of history, but also of contemporary Europe.

The Liber Chronicarum is also interesting as being published in 1493. In tone and focus the Liber is very backward-looking, and appeared in print just before Christopher Columbus' discoveries were to completely re-shape contemporary man's view of the World.

Schedel's World map is thus of the traditional Ptolemaic type, omitting Scandinavia, southern Africa and the Far East, and depicting the Indian Ocean as landlocked. The woodcut is flanked by the figures of Shem, Japhet and Ham, the sons of Noah, who re-populated the Earth after the Flood (incidentally, one of the most striking of the woodcuts set in the text is of the construction of the Ark).

On the left hand side, and printed from a separate block, are pictures of outlandish creatures, culled from classical and early mediaeval travellers' accounts. Rodney Shirley described the figures thus:

"Among the scenes are a six-armed man, possibly based on a file of Hindu dancers so aligned that the front figure appears to have multiple arms; a six-fingered man, a centaur, a four-eyed man from a coastal tribe in Ethiopia; a dog-headed man from the Simien Mountains, a cyclops, one of those men whose heads grow beneath their shoulders, one of the crook-legged men who live in the desert and slide along instead of walking; a strange hermaphrodite, a man with one giant foot only (stated by Solinus to be used a parasol but more likely an unfortunate sufferer from elephantisis), a man with a huge underlip (doubtless seen in Africa), a man with waist-length hanging ears, and other frightening and fanciful creatures of a world beyond"

One unusual feature of the map is the presence of a large island off the west coast of Africa. One possibility is that its presence might relate to the account of Martin Behaim's voyage to the region, which is incorporated by Schedel into his text.

The second map was apparently compiled by Hieronymus Münzer, a Nuremberg physician, who had travelled extensively throughout Europe, and who also contributed the accompanying text. Münzer's map clearly derives some information for Cardinal Nicolaus of Cusa's (or Cusanus) map of Germany and central Europe, but the many uncertainties about the publication history of the latter map, as described by Campbell and Karrow, do not allow a precise conclusion about the nature of the relationship. However, as Campbell pointed out, the geographical description in the text, and the delineation in the map do vary. For example, the map, copying Cusa, shows the Rivers Meuse and Rhine as following parallel courses to separate mouths in the North Sea, while in the text Munzer describes the two rivers flowing into a shared estuary.

While the text was compiled and edited by Schedel, much of the credit for this huge undertaking must go to the printer Anton Koberger, but more particularly to the two designers employed to work on the woodcuts - Michael Wohlgemuth and Willem Pleydenwurff, who cut the blocks, probably with the assistance of their pupil, Albrecht Durer.

Some of the woodcuts, particularly those symbolising the struggle of good versus evil have allowed plenty of opportunity for artistic expression, are powerful images, testament to the skills brought together to see this magnificent book through the press.

(Ashley Baynton-Williams, MapForum Issue 6)

Hartmann Schedel (1440-1514)

Nuremberg Chronicle 1493

Amongst all the magnificent books printed in the fifteenth century – which are known as incunables – one stands out as being the finest illustrated topographical work of the period: the Liber Chronicarum or Nuremberg Chronicle. Published by Hartmann Schedel and printed by Anton Koberger in July 1493 it contained a total of 1,809 woodcuts which include a Ptolemaic world map, a 'birds-eye' map of Europe and the first known printed view of an English town. These woodcuts were made by Michael Wohlgemut (Wolgemut) (1434-1519), and his son-in-law, Wilhelm Pleydenwurff. Wohlgemut was Dürer's tutor between 1486 and 1490.

Apart from its general interest as a very early descriptive topographical work, the Nuremberg Chronicle is also, by virtue of its date of publication, an historical document of the greatest importance. Issued seven months after Columbus landed in the New World, the Chronicle presents us with a 'lasť view of the known medieval world as seen by the peoples of Western Europe. Within a few years new editions were being issued incorporating news of the successful Atlantic voyages on the American continent; discoveries which proved to be key factors in the complex problems of mapping the modern world as we know it.

(Moreland and Bannister).