Leen Helmink Antique Maps & Atlases

www.helmink.com

Willem Lodewijcksz

Jacob van Neck

PREMIER LIVRE LE SECOND LIVRE

Certificate of Authentication and Description

This is to certify that the item illustrated and described below is a genuine antique

map, print or book that was first produced and published in 1601, today 425 years ago.

March 5, 2026

Cartographer(s)

Willem Lodewijcksz

Jacob van Neck

First Published

Amsterdam, 1601

This edition

1609 French edition

Size

cms

Technique

Copper engraving

Stock number

19617

Condition

Fine

Description

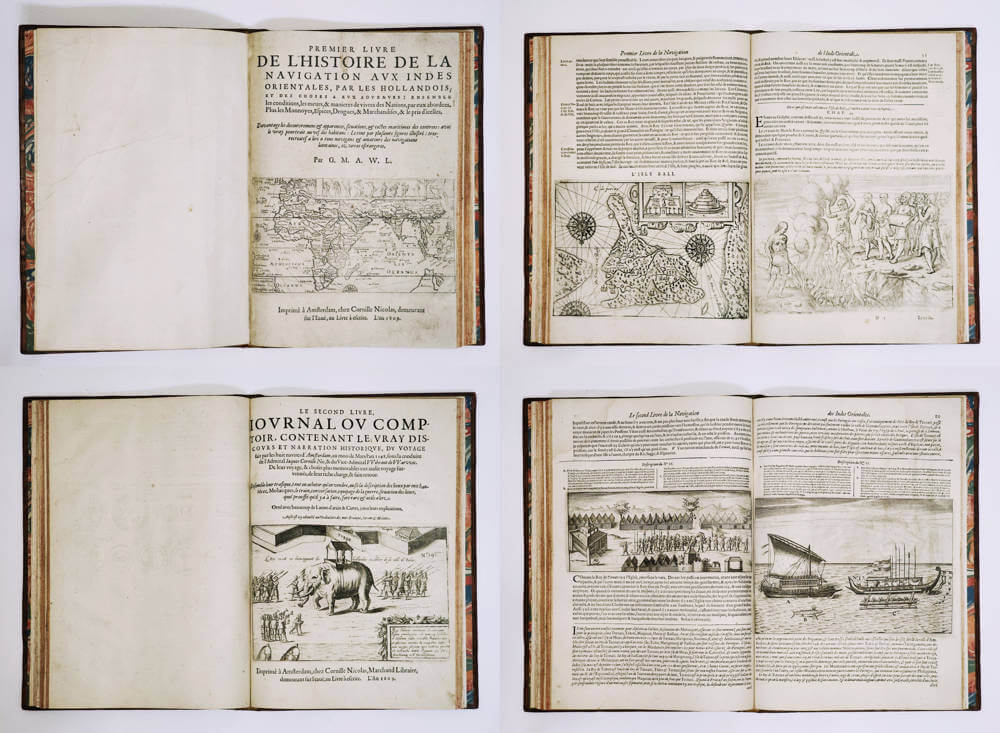

Two books bound in one

Matched pair of the Journals of both the first and the second Dutch fleet to the East Indies

Bound as companion pieces into one de luxe binding by the publisher at the time of printing

Amsterdam, Cornelis Claesz, 1609 uniform French editions

Willem Lodewijcksz: Premier livre de l'histoire de la navigation aux indes orientales, par les hollandois. 106 pagees (53 numbered leaves). Titlepage with engraved map, forty-five in-text engravings (including three maps), seventeen in-text woodcut illustrations, and one plate on separate leaf following printed text. Minimal thumbing on the titlepage, slight edge wear to a few leaves as always.

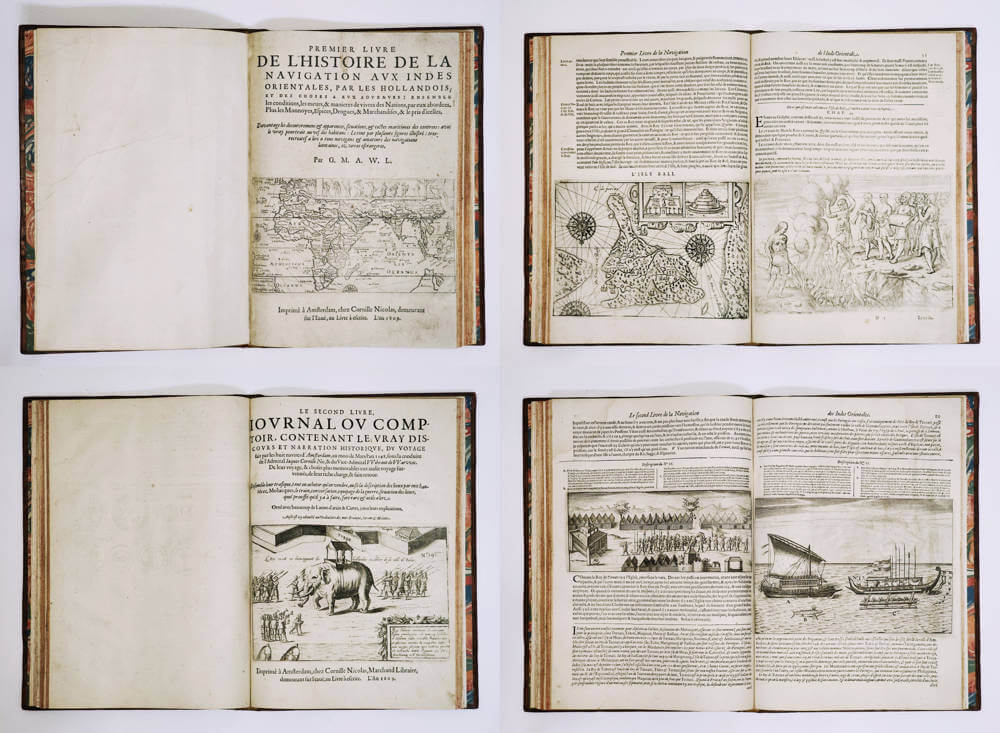

Jacob van Neck: Le second livre, iournal ou comptoir, contenant le vray discours et narration historique. Two parts. 44 pages (22 numbered leaves), followed by the first Javanese dictionary of 36 pages (18 leaves not numbered). Titlepages with engraved illustrations, twenty-two in-text engravings (including one map), two in-text woodcuts.

Contemporary smoothed marbled calfskin de luxe binding with spine label, richly gilt spine, gilt edges on the standing and red dyed inner edges. Marble endpapers. A magnificent example of two rare early journals, in very fine condition.

The voyages are of seminal importance to the exploration and the cartography of the region.

Lodewijcksz's journal as a first

The Lodewijcksz account is a first in many ways.

- first Dutch fleet to the Indies

- first printed ship's journal/log of a voyage of discovery

- first images of the Duyfken

- first ethnographic images of daily life in the Indian Ocean, Java, Sumatra, Bali

- first nautical profiles of the coasts of these areas

- first maps and views of Bantam

- first maps and views of Bali

- first printed images of the coins used in the area for trade

van Neck's journal as a first

The van Neck account is a first in many ways.

- first Dutch fleet to reach the Moluccas/Spice Islands (Banda, Ambon, Ternate and Tidore)

- first maps and views of the Spice Islands

- first ethnographic images of daily life in the Spice Islands

- first nautical profiles of the coasts of these areas

- first images of Dodo birds

- first Malay/Javanese dictionary

Enter the Dutch: the first and the second voyages to the East Indies

The dreams and labours of Petrus Plancius and Jan Huyghen van Linschoten culminated in the Dutch First Fleet to the Indies taking place from 1595 to 1597. It was instrumental in the opening up of the Indonesian spice trade to the merchants that would soon form the United Dutch East India Company (VOC). The first fleet reached the pepper port of Bantam, and went as far as Bali, before returning to Amsterdam.

This famous pioneering voyage, commanded by Cornelis de Houtman, would abruptly end the Portuguese Empire's trade monopoly for the East and it would dramatically change the Indian Ocean theatre, notably the balance of power and the rules of trade. Right from this first voyage onward, the Dutch were going to dominate the East Indies and its trade for more than 350 years.

Already in 1598, shortly after the return of the first fleet, the Amsterdam publisher Cornelis Claesz published an acclaimed account of the first voyage, written by Willem Lodewijcksz, an officer on the fleet. The journal was an instant success that sold in many editions and was translated in several languages. The journal’s title page has a small overview map of the route.

While the first fleet was not a commercial success, and suffered from great hardships and hostility from the Portuguese and the natives, it proved that the Spanish/Portuguese Empire and it's monopoly on overseas trade was vulnerable and could be challenged succesfully.

Shortly after the first fleet, Dutch merchants immediately organized a much larger second fleet using venture capitalist funding, and this fleet reached the Moluccas to buy spices without middle men and to establish trade relations there. The fleet was much larger and better organized than the first fleet, and the journal that was published in 1601 contains the first detailed printed maps of all of the different spice islands of Banda, Ambon, Ternate and Tidore, as well as the first printed views of their inhabitants.

The first and second fleet would abruptly end the Portuguese Empire's trade monopoly for the East and it would dramatically change the Indian Ocean theatre, notably the balance of power and the rules of trade. Right from the first and second fleet onward, the Dutch were going to dominate the East Indies and its trade for more than 350 years.

First Book: Willem Lodewijcksz Journal of the first dutch fleet to the Indies (1595-1597)

Already in 1598, shortly after the return of the first fleet, the Amsterdam publisher Cornelis Claesz published an acclaimed account of the first voyage, written by Willem Lodewijcksz, an officer on the fleet. The journal was an instant success that sold in many editions and was translated in several languages. The journal’s title page has a small overview map of the route.

According to Lach, this travel journal ‘provided European readers with the most detailed descriptions of Java to date and with the first continuous description of Bali in any language’. In 1598, the year after the return, Lodewyckszoon's account of the voyage instigated 'a flurry of activity among Dutch entrepreneurs' and no fewer than 25 ships set out from two provinces of Holland to the East Indies. Within a period of 18 months, the Dutch had established three trading posts in the Indies which became the foundation of their future control of the Moluccan spice trade and provided a foothold from which to launch further voyages eastward.

This first Dutch venture to the East Indies was instigated by Plancius and by Linschoten's Itinerario. Following their advice, the route took them across the Indian Ocean to the Sunda Straits. He stopped at Sumatra, engaged in trading in Bantam, and made further stops on the northern coast of Java. Lach emphasizes the importance of Lodewijcksz as the 'first eyewitness account of growing pepper and of coconut palms, along with descriptions of the people and other sights on the west coast of Sumatra'. The material on Java is very important, with elaborate ethnographical descriptions: there is an account of the institution of polygamy, a detailed description of a Javan wedding, music, dance, the writing system, language etc. The chapters on Bali present the first account and the first images and the first map of the island.

Lodewyckszoon's accurate coastline profiles were employed by later Dutch fleets, and the plates are among the earliest visual impressions formed by Europeans of this part of the world (Lach reproduces no less than a dozen). Some of the more interesting depict the merchants in Bantam (Peguan, Persian, Arab and Chinese), a Chinese temple (actually Hindu, the original religion which then still had presence on Java), the King of Bali in his ox-drawn chariot, a Javanese gamelan orchestra and a depiction of Javanese court dances (probably Gambang or Bedhaya).

The work appeared the same year in Dutch and French from the same publisher and went through a number of later editions.

Tiele, Memoire Bibliographique sur les Journaux des Navigateurs Neerlandais, p127.

Lach, Asia in the Making of Europe, III, 1.438-9 & III, 3. 1222-34.

Second Book: Jacob van Neck's Journal of the second dutch fleet to the Indies (1598-1600)

The book famously has the first engraving of a Dodo bird and the first accurate maps and views of the legendary Spice Islands. The journal ends with an eleven page appendix providing a dictionary of Malay and Javanese words, the first of its kind. The book was first published in 1602, here offered in the early French 1609 edition. The book has a famous and decorative title page view depicting a local ruler riding an elephant.

Despite its achievements, De Houtman's voyage did not live up to all of the commercial expectations. Even so, this voyage was a major stimulus to new expeditions to the East Indies. The fact was that the Cape route had been explored and the Indian Ocean lay open to the enterprising spirit of Holland and Zeeland. On the De Houtman voyage, the men had observed at first-hand the absence of the Portuguese fleet from the East Indian waters. During their stay on the coasts of Java, they had not seen a single Portuguese ship. In Amsterdam and Zeeland, it was realized that the Portuguese forces had been weakened to such an extent that a repetition of the first attempt had good chances of success - assuming they would not repeat the mistakes made on the first voyage. In 1598, in various cities of the Northern Netherlands, new fleets were fitted out to sail to the East Indies. The most important one was the fleet consisting of eight vessels under Admiral Jacob Cornelisz van Neck (1564-1638) and Vice-Admiral Wijbrant Warwijck (1570-?). The crew consisted of 560 men, including the merchant officer Jacob van Heemskerck, who had only been back from the winter ordeal on Novaya Zemlya for half a year. Van Neck's voyage was very important, because it was the first time that Dutch ships appeared in the waters of the eastern archipelago, around the Moluccan Islands. Moreover, by establishing lodges, the basis was laid for Dutch trade and the later settlement to be established in these areas.

Van Neck's fleet left its anchorage at Texel on 1 May 1598. Till the Cape of Good Hope, the voyage proceeded without any unusual incidents. But then, on 8 August, about 50 miles past Cape Agulhas, the vessels became separated in a heavy storm. Admiral Van Neck continued the journey with three ships, taking on fresh supplies on the island of S. Maria off the eastern coast of Madagascar and in the Bay of Antongil. Finally, on 26 November, his ships reached the roadstead of Bantam. Vice-Admiral Warwijck met up with him there five weeks later with the five ships that had strayed off. Warwijck had also spent a few days on the south coast of Madagascar, but he could not land there because of the heavy surf. It was then decided to sail directly to Java without taking on fresh supplies. In so doing, they took a great risk, but fortunately, on 17 September, the squadron sighted Ilha do Cerne, one of the Mascarene islands. They named the island Mauritius de Nassau, in honour of Prince Maurits. On the south side of that island, they found an excellent protected harbour, to which they gave the name Warwijck-haven, while the island lying at the entrance to the harbour was named Heemskerck-eiland. The men stayed on this deserted island for two weeks to allow those crewmembers suffering from scurvy to recuperate. On 2 October, they again set sail on a course toward Bantam, where they arrived on 31 December 1598.

In the meantime, Van Neck had already purchased a large amount of spices, enough to fill four ships. With these four (Mauritius, Hollandia, Vriesland, and Overijssel), Van Neck embarked on the homeward journey on 11 January 1599, while Warwijck was sent to the Moluccas with the other ships. Van Neck's voyage home went well; they only stopped at S. Helena to replenish the stocks and rest the men for a few days. On 19 July, the ships dropped anchor at Texel, and just over a week later Van Neck received a festive welcome in Amsterdam, where people were happy with the safe return of the ships and the rich cargo of pepper, cloves, mace, nutmeg, and cinnamon that they had brought with them. The whole journey had lasted not even 15 months. It had been so quick that the Portuguese living in Amsterdam did not believe that Van Neck had really been in the East Indies at all; they said that 'the goods must have been stolen half way'.

What had happened to the other ships in the meantime? In Bantam, on 4 January 1599, the General Council had decided that Warwijck, commanding four ships (Amsterdam, Zeeland, Gelderland, and Utrecht), would sail to the Moluccan Islands. He was to bear the title of admiral, while Jacob van Heemskerck was appointed vice-admiral. On 9 January, the squadron left the anchorage at Bantam. They sailed via Jakarta, Tuban, and Grissee on the coast of Java to Arosbaja on Madura. On 14 February, they continued their voyage, and on 3 March they dropped anchor at Hitoe on Ambon. There, the supply of spices proved to be insufficient. Thus, Warwijck, in turn, sent Van Heemskerck with the Zeeland and the Gelderland on to Banda to obtain a cargo. There, the trading negotiations went so smoothly that Van Heemskerck could already start the voyage home at the beginning of July, carrying a rich cargo of nutmeg. He established the first lodge of the Dutch in the Moluccas, leaving 20 men behind with commercial appointments and money so they could already buy nutmeg and mace for subsequent Dutch ships. Five months after leaving Banda, Van Heemskerck's ships lay at anchor at S. Helena to take on supplies. On 1 January 1600, they continued their voyage, and at the end of April the ships arrived safely at Texel.

On Ambon, Admiral Warwijck could only obtain a small cargo. Therefore, on 8 May, after a stay of two months, he decided to sail on to Ternate, which he reached on the 23rd. There, they loaded as much cloves as they could purchase and started the homeward journey on 19 August. Six men were left behind for the sake of future commercial relations. On the return trip, they stopped again at Bantam on 17 November to supplement the cargo. On 21 January 1600, they resumed their voyage. The presence of Portuguese ships at S. Helena prevented them from landing there, and later, on Ascension Island, they were only able to obtain a small amount of fresh food. Thus, scurvy cropped up on the ships. Finally, Warwijck reached the anchorage at Texel at the beginning of September 1600.

All eight ships of the Second Voyage had returned safely and brought the shipowners great profits. An important result was that the Hollanders had found and explored the route to the Moluccas themselves, and consequently they no longer had do deal through Portuguese intermediaries.

In 1599, soon after Admiral Van Neck returned with four ships, a description of his voyage was published. Although not a single copy of that work has been preserved, the existence of that publication was confirmed by Emanuel van Meteren. In the very same year, an English translation appeared in London. Then, in 1600, after the remaining four ships had also returned, a report was published describing the adventures of the entire expedition. The report, entitled Journael ofte Dagh-register, was published in Middelburg by Barent Langenes and in Amsterdam by Cornelis Claesz. An English translation of that work was published in London in 1601. However, the Amsterdam edition of 1600 was already replaced in 1601 by a more extensive Tweede Boeck, which formed the basis for all subsequent editions and translations.

(Schilder)

Willem Lodewijcksz

Willem Lodewijcksz was a Dutch naval officer and author, known for his detailed account of the first Dutch expedition to the East Indies from 1595 to 1597. This pioneering voyage, led by Cornelis de Houtman, marked the beginning of Dutch involvement in the spice trade and the establishment of the Dutch East India Company (VOC).

Lodewijcksz's journal, titled D'eerste boeck: Journal ofte beschrijvinghe van de reyse gedaen by de Hollandtsche schepen, provides a comprehensive narrative of the expedition. It offers insights into the challenges faced during the journey, interactions with local populations, and observations of the regions visited. His work is considered one of the earliest and most valuable Dutch accounts of Southeast Asia.

While specific personal details about Lodewijcksz are scarce, his contributions as a chronicler have been instrumental in understanding early Dutch maritime exploration and the subsequent expansion into the East Indies.

We do know from his own journal and from other sources that he was well educated in navigation and in commerce, and that he was fluent in Spanish, Portuguese and Italian.

He was important enough to take part in the ship's councils during the expedition, and was part of commercial and navigational decisions.

Possibly worried about repercussions for spreading secret information, the journal's author is named only as "G.M.A.W.L.", which was only centuries later deciphered as

G(uillaume) M(..) A(lias) W(illem) L(odewycksz)

.Interestingly, he was added to the fleet at the very last minute, on the day it was sailing, after it had already spent 10 days of waiting for favourable winds at Texel roadstead. He was added by the Amsterdam faction venture capitalist investors of the fleet, as an "Adelborst", a gentleman officer. These were the well educated young sons of successful citizens brave enough to risk their lives for a steep career in commerce and navigation.

As IJzerman notes:

On the final day of the ships' stay, Saturday, April 1, 1595, so to speak, at the very last moment, Lodewycksz came aboard the Amsterdam. He was accompanied by "some" of the shipowners (who exactly?) and had traveled from Amsterdam to Texel on Wednesday, March 29. The ships had already been anchored there since March 21, while some cadets, including Van der Does, had also traveled overland to Texel on Easter Sunday, March 26.

At the very last moment, Lodewycksz was extraordinarily appointed to the ship bearing the name of the departing Amsterdam. As evidenced by his entire First Book, he acted as a "mediator" between the factions that were noticeable from the very beginning: those on the Mauritius, the Prince's ship, led by Cornelis de Houtman as the senior merchant, and those on the Hollandia, the States' ship, where Houtman's fierce rival Gerrit van Boninghen served as merchant.

Lodewycksz was able to participate in the entire voyage and, in the end, omitting or glossing over all disputes, was able to write the official account of the First Expedition on behalf of the Amsterdam shipowners.

Jacob van Neck (1564-1638)

Jacob Corneliszoon van Neck (often anglicized to Jacob Cornelius van Neck) (1564 – March 8, 1638) was a Dutch naval officer and explorer who led the second Dutch expedition to Indonesia from 1598 to 1599.

Van Neck was from an Amsterdam family in good standing, and received a thorough education. Since he came from a commercial background and was not experienced in sailing, he took extra classes in navigation.

Following the success of the first Dutch expedition to Indonesia in 1597, Van Neck was chosen to lead a second expedition in 1598, with the purpose of bringing back various spices. In May 1598, he left the port of Texel with eight vessels under his command.

He was accompanied by Vice-Admiral Wybrand van Warwyck and noted polar explorer Jacob van Heemskerk.

Following sailing directions written by Petrus Plancius, they made excellent progress, reaching the Cape of Good Hope in only three months.

Soon after this, heavy storms separated Van Neck, with three ships, from the rest of the fleet under Warwyck. Neck landed on the east coast of Madagascar and replenished his supplies, then continued on towards the Indonesian city of Bantam. He reached it on November 25, 1598, after less than seven months of sailing. Within one month, all three of his ships had been filled with spice, and on December 31 the other half of the fleet sailed into port at Bantam, prompting a huge New Year's celebration. Van Neck filled one more ship full of spices, making four ready to be sailed back to Amsterdam, then sent Warwyck and Heemskerck with the other four ships to the east in order to procure more spices. Van Neck then took the four ships that had been loaded with spices back to Amsterdam, where he arrived July, 1599.

He brought back with him nearly one million pounds in weight of pepper and cloves, in addition to half a ship full of nutmeg, mace, and cinnamon. The explorers were greeted by an ecstatic Amsterdam and paraded through the city behind a band of trumpeters, with every church bell tolling. The merchants who had backed the voyage rewarded Van Neck with a gold beaker (it later turned out to be only gold-plated) and the crew were given as much wine as they could drink.

The voyage was a tremendous success, earning the backers a 400 percent return on their investment.

Van Neck made one more expedition to the Indies after his voyage of 1598, losing three fingers while doing battle with a Spanish-Portuguese fleet near Ternate. He retired from exploring after that, and later became a mayor of Amsterdam, and alderman, and a member of two admiralty colleges. He died on March 8, 1638.

(Wikipedia)