Leen Helmink Antique Maps & Atlases

www.helmink.com

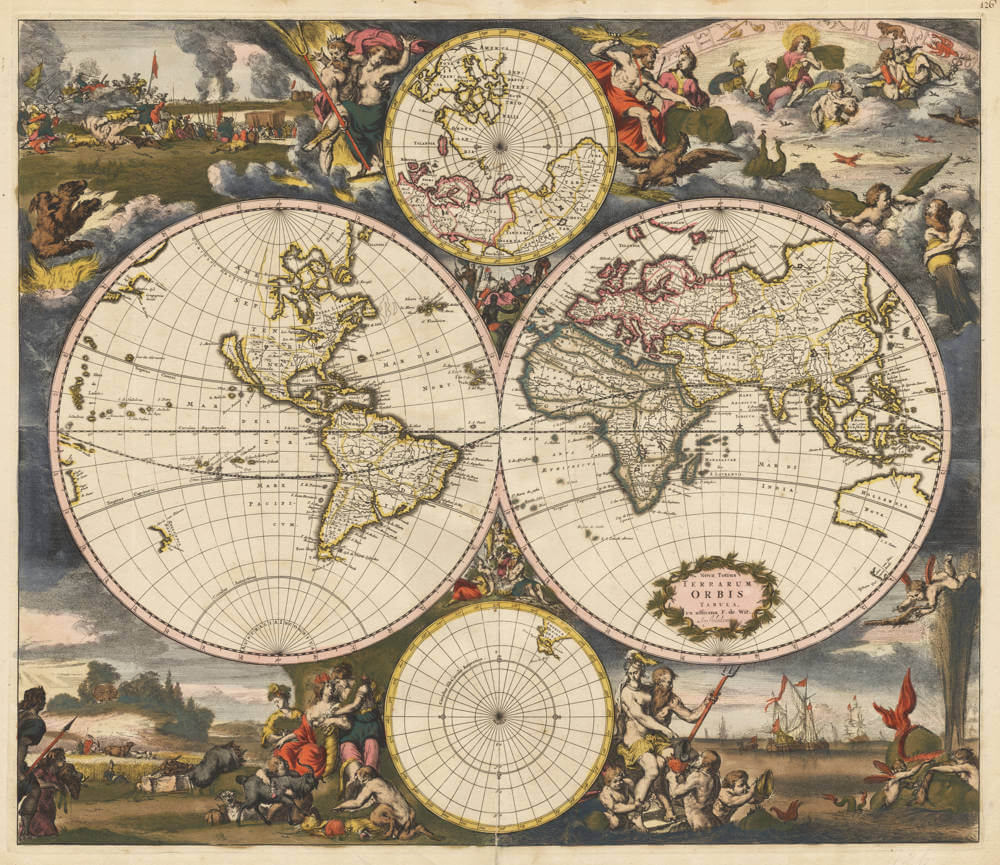

Frederick de Wit / Romeijn de Hooghe

Nova Totius Terrarum Orbis Tabula ex officina F. de Wit. Amstelodami

Certificate of Authentication and Description

This is to certify that the item illustrated and described below is a genuine antique

map, print or book that was first produced and published in 1668, today 358 years ago.

February 13, 2026

Cartographer(s)

Frederick de Wit / Romeijn de Hooghe

First Published

Amsterdam, 1668

This edition

1668 first state

Size

48.1 x 56.2 cms

Technique

Copper engraving

Stock number

19581

Condition

excellent

Description

The exceptionally rare first state of Frederick de Wit's fine maritime world map, the opening overview map from his sea atlas Orbis Maritimus Ofte Zee Atlas, with sea charts of all regions of the world.

The map is one of the most spectacular maps of the Dutch Golden Age of mapmaking.

The mythological decorations around the map were designed and etched by Romeyn de Hooghe, the unrivalled artist and etcher who was highly admired by his contemporaries. Frederick de Wit's map is considered a supreme example of Dutch 17th century mapmaking, and is often refered to as the most beautiful of all world maps from the Dutch Golden Age. It is considered a masterpiece, cartographically as well as an art-historically, offering an extraordinary symbiosis of cartography and iconography.

The Mapping of the World

The date of De Wit's fine maritime map can just be discerned below the signature of the important Dutch engraver and artist Romeyn de Hooghe in the lower left-hand corner. The title is in a small cartouche on the eastern hemisphere. Somewhat unusually the two main hemispheres have been engraved and the surrounding illustrations etched. In the corners are large and lively scenes allegorically representing the four elements. Fire is shown by war and destruction; air by the heavens; earth by harvesting and husbandry; and water by ships and a spouting whale. There are groups of figures between the hemispheres and, above and below them, two smaller polar maps.

De Wit's atlases are rarely dated: Koeman gives the first definitive date of his maritime atlas as 1675 but earlier collections of such maps are ascribed to c. 1670. They typically include this map which is described in the printed list of maps as the Orbis Maritimus. It was issued a number of times over the next thirty years and then in the eighteenth century maintained in circulation with amendments to the title cartouche as listed below:

State 2 L. Renard (1715 and 1739)

State 3 R. & J. Ottens (1745)

State 4 widow of G. Hulst van Keulen (1802)

Note the similar map, enlarged to four sheets, and the single-sheet copies made by Justus Danckerts in c. 1680 and c. 1685, by Gerrit van Schagen in 1682, by Joachim Bormeester in c. 1685 and by David Funcke in c. 1700.

(Rodney Shirley map 514).

Geographical content

Geographically, there is much progress in comparison with the 1655-1658 second edition of Joan Blaeu's 1648 large double hemisphere wall map of the world (Shirley 371), which was the gold standard at the time. In the interior of North America, the large inland lake has been replaced by an improved depiction of the Great Lakes. Japan has been completely changed. The northeast end of Siberia is now almost connected to Japan and to a Compagnies Land, sighted in bad weather by Maarten de Vries in 1643. These adjustment to Blaeu’s wall map have however not been added to the Arctic map at the top of the map. The coastlines on the east side of the island of Spitsbergen have been expanded. Of special interest is that the usual "unknown southern continent" (Terra Australis Incognita) has disappeared altogether. A prominent place in the map image is the depiction of HOLLANDIA NOVA with the results from the voyages of discovery by Abel Janszoon Tasman (1642/43 and 1644) and his predecessors on the north, west and south coast.

The iconography of Romeijn de Hooghe

The double hemisphere map of the world is surrounded by extensive decorations etched by Romeyn de Hooghe's for Frederick de Wit.

As with many of De Hooghe’s works the design of the etchings is a complex one. It is not a random arrangement of decorative elements, but a carefully balanced scheme. The hemispheres are surrounded by allegoric representations of the four elements, the four seasons, the four continents and the seven greek gods corresponding to the seven planets, very popular motifs in 16th and 17th century Dutch graphic art. It expresses the need of mankind to establish order in the world. Dating back to ancient Greek science and philosophy, the four classical elements were considered to form the structure of the universe. A relation was assumed between the four elements and the seasons. Spring corresponded to Air, Summer to Fire, Autumn to Earth and Winter to Water. Together the seasons and the elements depict a cosmic order in which everything is related in one global harmony.

Upper right scene: Air

The grand scene in the upper right section of the map has an entirely mythological content, showing the important seven gods of the Olympus, home of the gods of the upper world. Each of the god is associated with one of the seven planets that were known in classical antiquity and Renaissance.

From left to right, the first figure we encounter is Zeus (Jupiter), the king of all gods and ruler of the upper world. He is depicted with his symbols of the eagle and the flaming arrows of lightning. Zeus is accompanied by his wife Juno (Hera), who was also his sister. She is the goddess of marriage. Her symbols, the two peacocks who stay together for life are next to her. She is depicted wearing a goatskin cloak to emphasize her warlike aspects. The star on his head refers to the planet Jupiter, named after him.

The man and women seated in the clouds are Ares (Mars), god of war, and Aphrodite (Venus), goddess of love. He is easily recognisable by his helmet, sword and shield; she is holding a burning heart of love. The stars on their head refer to the planets named after them.

In front of them is Apollo (Helios), the Olympian god of the sun and light, music and poetry. He is depicted with a lyre, his common attribute, and surrounded by a bright sun halo.

The old man with a scythe, eating a child, depicts Cronus (Saturn), the forefather of the classical gods, also god of agriculture and harvest, and a symbol of the passing of time and history. Because of a prediction that one day a mighty son would overthrow him, he ate all of his children when they were born to prevent this. Cronus’s wife Rhea hid her sixth child, Zeus, and offered Cronus a large stone wrapped in clothes which he promptly devoured. Zeus later managed to overthrow him. Cronus' star refers to the planet Saturn, named after him.

Going further, the figure in the clouds with the winged helmet and staff with intertwined snakes is Hermes (Mercurius), messenger to the gods and protector of trade and negotiation. The large owl next to his feet is not just a bird, she is the symbol of Minerva, goddess of wisdom and reason. He is sitting with Diana, the goddess of the hunt and moon and birthing. She is depicted with her typical symbols spear, bow and arrows and a moon disc over her head.

In the lower right is the river god Potamoi, god of rivers and streams of the earth, and son of the great earth-encircling river Oceanus, shown as an old man with his arm resting on a pitcher ouring water streams. Next to him is the wind god Anemoi.

The scene is topped with part of the zodiac showing (from right to left) the subsequent signs of Cancer, Leo, Virgo, Libra and Scorpio (the Crab, the Lion, the Virgin, the Scales and the Scorpion).

This panel is a depiction of the Olympus or home of the gods. From the important gods only Poseidon (Neptune) and Hades (Pluto) are missing, and they are used in two other panels.

Lower right scene: Water

The scene in the lower right is decicated to the classical element of water.

After the gods defeated the Titans, the world was divided into three and Zeus, Hades and Poseidon drew straws to decide which they would rule. Zeus drew the skies, Hades the underworld, and Poseidon the seas. There is only one reference to this divide, by Homer in the Iliad. Poseidon (Neptune) was god of the sea, earthquakes, storms, and horses and is considered one of the most bad-tempered, moody and greedy Olympian gods. He was known to be vengeful when insulted. Because of his influence on the waters, he was worshipped in connection with navigation. He is shown with his trident attribute and his wife Amphitrite, a Nereid. Their union produced Triton, who was half-human, half-fish, and shown here offering them a shell. The waters in the background are filled with Dutch merchant ships.

Upper left: Fire

The scene in the upper left is decicated to the classical element of fire. The background depicts the horrors of wars, and on the right we see Hades and his spouse Persephone. Hades (Pluto) is best known as the ruler of the underworld. It became his dominion after he and his brothers Poseidon and Zeus drew lots for their share of the universe. The god of the underworld was married to Persephone, the daughter of Demeter, whom he obtained through deception after abducting her to the underworld and giving her the forbidden fruit pomegranate, forcing her to remain in the underworld with him for one third of each year.

On the left is Cerberus the three-headed dog who guarded Hades' realm. The primary job of Cerberus in Greek mythology was as a watchdog for the underworld. He was also a faithful servant to Hades. The three-headed dog prevented those were dead from escaping, as well as kept the living from going there without the permission of Hades. Cerberus was very kinds and friendly to the dead, as well as any new spirits who entered the underworld. He would also become savage and would eat any of them who tried to get past him and go back to the land of the living. The mother of Cerberus was Echidna. She was a creature that was half snake and half human woman. She had the head and torso of a beautiful woman. Echidna was known for her deep black eyes. The lower part of her body was that of a serpent. She lived in a cave and lured men there before she consumed them.

Lower left scene: Earth

The scene in the lower left is decicated to the classical element of earth.

The figure seated is Cybele, the earth-goddess and the goddess of towns, with her turreted crown. She is also known as the city virgin, an allegorical depiction of the city of Amsterdam. Crowned with a tiara in the form of a citywall, she symbolizes the power and wealth of Amsterdam. The scene is shows harvesting and husbandry.

Rarity

The map is extremely hard to find, even more so in first state and in excellent condition and early colour. It was sold as a separate map, and occasionally (but not always) included in De Wit's Maritime Atlas from ca 1670 onwards.

Condition

Rare first state (of four) of this seminal map, with the address of Frederick de Wit. Here in rich and vibrant original colour. A strong early and even imprint of the copperplate. Printed on thick paper, with ample margins all around. Overall an excellent collector's example of an iconic map of the world.

Frederick de Wit (1629-1706)

Early Life and Beginnings in Amsterdam

Frederick de Wit was born around 1629 in Gouda, a city known for its cultural and intellectual contributions during the Dutch Golden Age. His family was Protestant, and by 1648, 18 or 19 year old De Wit had moved to Amsterdam, a city at the heart of Dutch trade, culture, and mapmaking. Here, he served his apprenticeship under the tutelage of Joan Blaeu, whose family was already famous for producing some of the world's finest atlases and maps.

Establishment in Amsterdam

In 1654, de Wit set up his own printing office and shop, initially named "De Drie Crabben" (The Three Crabs), which was also the name of his residence on Kalverstraat. The following year, he renamed it "De Witte Pascaert" (The White Navigation Chart), signaling his focus on cartography. His early works included a plan of Haarlem in 1648 and illustrations for Antonius Sanderus’s "Flandria Illustrata", but it was his independently engraved map of Denmark in 1659 that marked his entry into the broader mapmaking world.

Cartographic Contributions and Style

De Wit's maps were distinguished by their accuracy, decorative borders, and elaborate cartouches often depicting classical mythology or allegorical scenes. His most famous work, "Nova Totius Terrarum Orbis Tabula," was a world map first published in 1660. The map demonstrated his skill in both geography and artistic design. Over the decades, he produced numerous sea charts, town plans, and wall maps, which were not only navigational aids but also sought after for their beauty and decorative value.

By the 1670s, de Wit was producing larger atlases like the "Atlas Maior" and "Nieuw Kaertboeck van de XVII Nederlandse Provinciën". These atlases combined his own engravings with those he had acquired, showcasing his entrepreneurial spirit. His maps of the Netherlands were particularly notable for their detailed depiction of the Dutch landscape, including cities, waterways, and dykes, reflecting the country's complex relationship with its environment.

Personal Life and Guild Membership

In 1661, de Wit married Maria van der Way, which not only brought him personal happiness but also the privileges of Amsterdam citizenship. This allowed him to join the prestigious Guild of Saint Luke in 1664, which was essential for artists and engravers in the city. His involvement with the guild underscores his standing in the artistic community of Amsterdam.

Later Years and Legacy

De Wit's business thrived, especially after the death of his mentor Blaeu, from which he acquired many copper plates when they were dispersed at auction, positioning him as one of the leading cartographers in Amsterdam. He continued to expand his catalog, ensuring his maps were up-to-date with the latest geographical discoveries. His attention to detail and the aesthetic quality of his work made his maps popular among the elite, scholars, merchants, and navigators alike.

When Frederick de Wit passed away in July 1706, his wife Maria managed the business until 1710. After her death, the vast collection of copper plates was auctioned off, with many going to Pieter Mortier (1661-1711), who used them to further his own publishing empire, Covens & Mortier. In 1721, the copperplates were sold in auction by the heirs of Mortier's widow, and were acquired by the Ottens publishing house in Amsterdam. These transactions illustrate de Wit's lasting influence on the mapmaking industry.

Cultural Impact and Modern Appreciation

De Wit's work encapsulates the spirit of the Dutch Golden Age – a period of unprecedented artistic and scientific achievement. His maps are not merely tools for navigation but are also pieces of art that reflect the cultural pride of the Dutch in their maritime and cartographic prowess. Today, his maps are treasured in collections around the globe, from libraries to smaller, specialized map collections. They are frequently exhibited in museums as exemplars of the Dutch art of cartography, admired for their precision, beauty, and historical significance.

Frederick de Wit's legacy is one of a craftsman whose maps not only charted the physical world but also captured the imagination of those who used them, contributing to the enduring allure of an age when maps were as much about exploration as they were about art.

Romeyn de Hooghe (1645-1708)

During his lifetime, the etcher Romeyn de Hooghe (Amsterdam 1645 – Haarlem 1708) was renowned as the most important graphic artist of its era. “Who wants to learn the art of etching, should become an apprentice of the very well educated Romeyn de Hooghe”Inleyding tot de hooge schoole der schilderkonst (Introduction to the academy of the art of painting).

This enthusiasm for the work of De Hooghe was still unchanged in the twentieth century. The famous Austrian art historian Otto Benesch considered Romeyn de Hooghe as “the most genius Dutch illustrator and one of the most important etcher of all times. His work united the universality of baroque, of which in Holland he was the last representative of European stature ...” [Otto Benesch, 1964, p. 368].

The versatility and high artistic quality are characteristic of the works of Romeyn de Hooghe. His illustrations and loose prints cover all possible subjects. De Hooghe illustrated books of every conceivable genre. In the area of loose prints, special attention is attracted to the numerous news prints, allegories, portraits, maps, topographical prints and costume prints. A good insight in his many-sided work is offered by the publications of Landwehr (1970 and 1972).

Romeyn de Hooghe also designed and etched numerous title pages of books. One of the oldest of his hand is the frontispiece of Nicolaas Witsen’s Aloude en Hedendaegsche Scheeps-Bouw en Bestier (1671). Witsen was the leading authority in the area of ship building and ship design in the late 17e century, and his profusely illustrated publications were famous internationally.

A remarkable aspect of the style of Romeyn de Hooghe is the extremely fluent and smooth manner of drawing and etching. The illustrations are filled with many human figures that suggest action: everywhere is activity and motion. Seen from a distance, the crowds have a shaping quality; a closer look reveals however a huge amount of narrative details. Especially striking are the facial and emotional expressions of the people who are depicted. In much of his work he combines often newly invented allegorical elements, inspired by classical antiquity and the Bible, with more concrete and contemporary representations. With his pictorial technique he tried to achieve emotional involvement from the spectator. This effective combination of erudition and inventiveness, of imagination and sensationalism, made his work irresistible for his contemporaries and has lost none of its charm today.

In addition to graphic art, Romeyn de Hooghe was closely involved in the design and manufacture of cartographic works. Notable examples are the large and decorative overview wall maps of Delft (1675-78), Haarlem (1688-89), Rotterdam (1694) and the Hoogheemraadschap (Water Board) of Rijnland (1687). These maps consist not only of a cartographic image, but are surrounded by city profiles, coat-ofarms of governors, decorations, separate title banners etc. Another famous example is the large portolan chart of

maritime cartography of the 17th century.

Romeyn de Hooghe rapidly developed himself to the most productive and the most popular etcher of his time, and he produced a great amount of prints for various purposes, from small book illustrations to luxury print series on large format. Despite all this, very little of his work has come to us in colour, especially in the form of his loose prints or loose charts.

Literature

Otto Benesch, Meisterzeichnungen der Albertina, Salzburg, 1964.

John Landwehr, Romeyn de Hooghe (1645-1708) as book-illustrator. A bibliography. Amsterdam, 1970.

John Landwehr, Romeyn de Hooghe the etcher. Contemporary portrayal of Europe 1662-1707. Leiden, 1972.

Georges Keyes (ed.), Mirror of Empire. Dutch marine art of the seventeenth century. Minneapolis: The Minneapolis Institute of Art, 1990.

Günter Schilder, A manuscript sea atlas, drawn by Romeyn de Hooghe in 1681. In: Publicacoes do Centro de Estudos de Cartografia Antiga. Vol. 130 (Coimbra 1981) 17 pp.

Günter Schilder, Dutch wall maps of the 16th, 17th and 18th Century. To be published, 2024.

Günter Schilder, personal communication.

Henk van Nierop et. al. (eds), Romeyn de Hooghe. De verbeelding van de late Gouden Eeuw. Zwolle: Waanders Uitgevers / Amsterdam: Bijzondere Collecties van de Universiteit van Amsterdam, 2008. Exhibition Catalogue.

Henk van Nierop, The Life of Romeyn de Hooghe 1645-1708. Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2018. Exhibition Catalogue.