Leen Helmink Antique Maps & Atlases

www.helmink.com

Thomas Waghorn

Chart shewing the Route of Steam Communication between England & Australia ...

Certificate of Authentication and Description

This is to certify that the item illustrated and described below is a genuine antique

map, print or book that was first produced and published in 1846, today 180 years ago.

March 10, 2026

Cartographer(s)

Thomas Waghorn

First Published

Melbourne, 1846

This edition

Size

22 x 28 cms

Technique

Copper engraving

Stock number

19507

Condition

very good

Description

Thomas WAGHORN (1800 - 1850). / Thomas HAM (1821 - 1870), Cartographer.

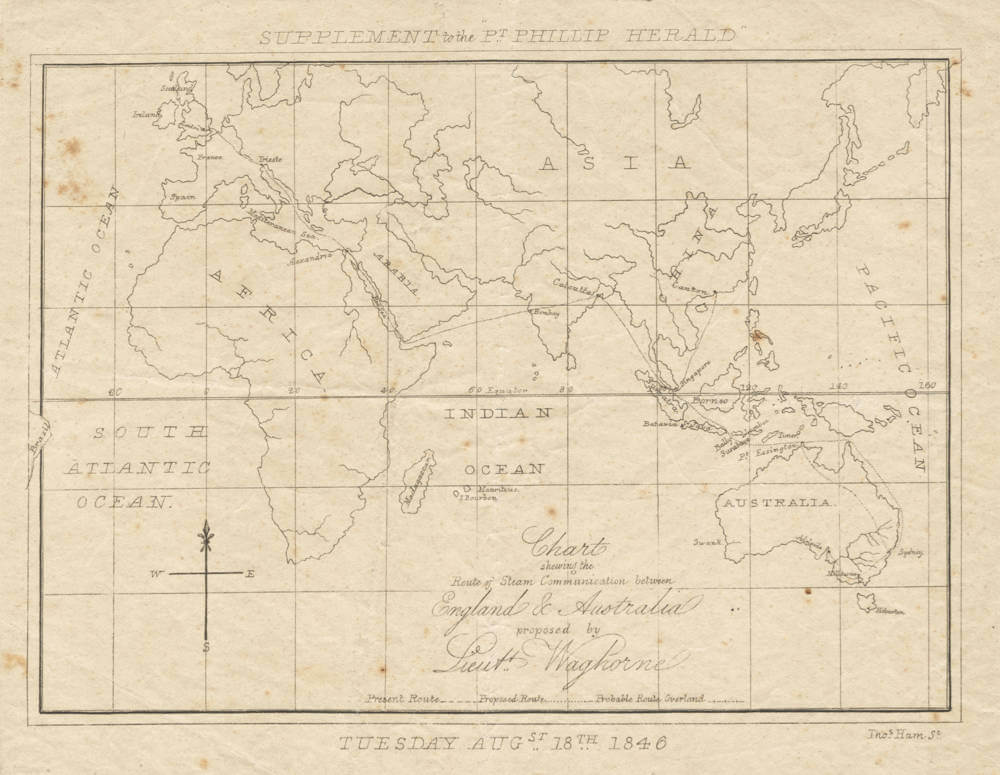

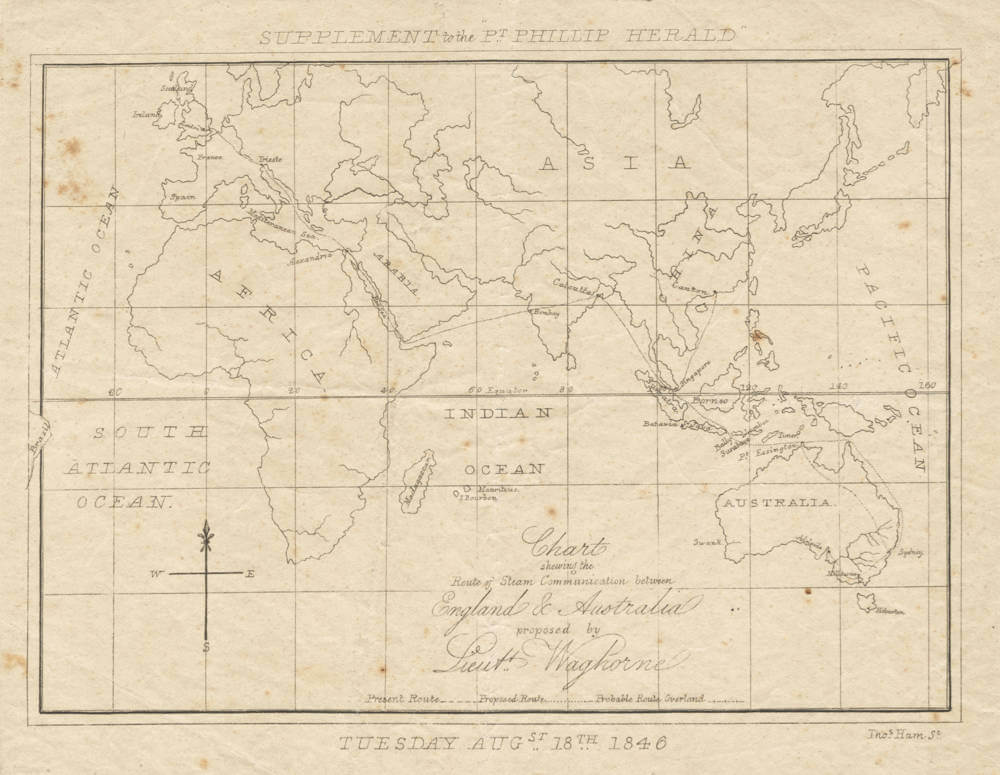

Chart shewing the Route of Steam Communication between England & Australia proposed by Lieutt. Waghorne.

Supplement to the Pt. Phillip Herald, Tuesday Augst. 18th 1846.

[Melbourne:] Thomas Ham for the Port Phillip Herald, 1846.

Lithograph (Very Good, just some light foxing), 22 x 28 cm (8.5 x 11 inches).

An extremely rare broadside map depicting the proposed new ‘fast’ steamship route from Singapore to Sydney that promised to cut the travel time from England to Australia by half, as devised by Thomas Waghorn, the era’s great and controversial visionary of global transportation, the work drafted by Thomas Ham, the father of map printing in Victoria, published in Melbourne as a loose supplement to the ‘Port Phillip Herald’.

Thomas Waghorn was a famous and controversial figure who during the 1830s and ‘40s was perhaps the world’s most prominent promoter of new proposals to make transportation between Europe, India and Australia faster and more reliable. From 1837 to 1844, he operated a business that transported mail and passengers across the Suez Peninsula, so dramatically reducing the travel time between England and India. While that enterprise eventually failed commercially, from 1845 Waghorn set his sights upon creating a fast link to Australia, to the benefit of trade, communications and immigration.

Waghorn noticed that while by the mid 1840s the fast travel route from England to India was well-established (in part due to his own efforts), developing expeditious links onwards to Australia was a neglected opportunity. Up to this point, the usual route between England and Australia was the horrifically long passage around the Cape of Good Hope that took least 120 days. This placed a severe damper upon Australia’s potential, as while New South Wales imported on average £1.5 million of goods per annum from Britain, this amount would surely grow in a major way if transport links were improved. Moreover, immigration to Australia could be increased dramatically, to the benefit of that underdeveloped land, if the passage was not so forbiddingly long and unpleasant.

In a May 1846 address to Colonial Secretary William Gladstone, Waghorn wrote:

“It is not for me to call your attention to the political and commercial importance of Australia, New Zealand, & c. You are far better aware of it than I can possible pretend to be. You well know the magnitude of that fifth part of the earth – equal in extent to the whole of Continental Europe. You know the impediments that prevent its development, by reason of its extreme remoteness from the parent state. You know its resources. You have, perhaps,casually,made a guess in your own mind of the degree to which those resources might be called forth, were that distance diminished materially - were Port Jackson and London brought two or three months nearer than at present …”

(Waghorn, Letter to the Rt. Hon. Wm. Ewart Gladstone,pp. 3-4).

Waghorn believed that a far faster and more pleasant route from England to Australia could be found be developing a 4,450-mile-long steamship route from Singapore to Sydney (the full London to Sydney trip, via the Suez and India, totaled 11,700 miles). This would allow one to travel from London to Sydney in 60-65 days, roughly having the established travel time.

Waghorn aggressively promoted the Singapore-Sydney steamship line concept in England, the East Indies and Australia, seeking to gain seed money from the crown and private investors. The premise that Australia could be brought much closer to the home country naturally sparked great excitement, especially in Sydney and Melbourne. This is where the present map enters the scene.

Responding to the intense public interest that Waghorn’s proposal generated in Australia, the present map was drawn and lithographed by Thomas Ham, who had recently established himself as the father of map publishing in Melbourne. It was made to be a loose-leaf insert, or supplement, to the August 16, 1846 issue of the Port Phillip Herald, the city’s leading newspaper.

The present map, lithographed in a charmingly crude colonial style, embraces Europe, Africa, Asia, Australia and New Zealand. The legend, at the bottom identifies the various transport routes depicted, being the Present Route (dashed line); Proposed Route (dotted line); and the Probable Route Overland (dashed and crossed line). The Present Route delineates the well-established ‘fast’ route from England to Calcutta (mixed steamship and overland) and from there on to Singapore and Canton, China. The Proposed Route shows Waghorn’s envisaged new steamship route from Singapore to Sydney, via intended coaling stations at Surabaya, Bali or Lombok, and Port Essington (northern Australia). While less developed, Waghorn’s Probable Route Overland refers to the possible terrestrial routes from Port Essington to Sydney, and then on to Melbourne and Adelaide, that would avoid adverse sea currents, and could perhaps one day be served by railways.

Waghorn wrote several formal proposals and published pamphlets in London to promote both his Singapore-Sydney steamship conceptions, as well as to encourage Australian immigration. Despite his intense and high-profile lobbying campaign, the Crown eventually declined to support his project, due to the considerable costs involved. However, as was the case with his previous work in developing a transport route across the Suez Isthmus, Waghorn paved the way for others to successfully follow through on such ventures in the succeeding years. In short, Waghorn proved that such a route was both possible and advantageous, it was just some years ahead of its time. It was not until the Australian Gold Rush (1851 – c.1869) that the considerable capital became available to ensure that a fast route from England to Sydney and Melbourne (via Egypt, India and Singapore) would become a commercially viable reality.

Editions and Rarity

We are aware of two states of the map. The first appears to be a proof, missing Ham’s imprint, a few small details on the map, and the line regarding the Port Phillip Herald. It is known in only a single example, held by the National Library of Australia.

We can only trace a single institutional example of the present state of the map, held by the State Library of Victoria. Moreover, we are not aware of any sales records for other examples. The great rarity of the map is not surprising, as the survival rate of such ephemeral pre-Gold Rush era Victorian imprints is extremely low.

References:

State Library of Victoria: MAPS SB 100 GMFS 1846 HAM., OCLC: 854851520; Cf. (Re:

proof state:) National Library of Australia: MAP RM 1397, OCLC: 225162300; (Re: Waghorn’s

contemporary promotional pamphlets:) Thomas Waghorn, Letter to the Rt. Hon. Wm. Ewart Gladstone,

M.P.: Secretary of State for the colonies, on the extension of steam navigation from Singapore to Port

Jackson, Australia (London: Smith, Elder, and Co., Cornhill, 1846); Thomas Waghorn, Mr. Waghorn’s

second pamphlet on steam communication with Australia, via Singapore: letter to the Rt. Hon. the Earl

Grey, on the extension of steam navigation from Singapore to Port Jackson, Australia (London: Smith,

Elder, and Co., Cornhill, 1847); Thomas Waghorn, Waghorn on Emigration to Australia on the broadest

possible principles, for the future amelioration and prosperity of Great Britain. Dedicated to Earl Grey,

etc. (George Mann; James Ridgway: London, [1848]).

(Antiquariat Dasa Pahor)

Thomas Fletcher Waghorn (1800 - 1850)

Thomas Waghorn: Controversial Visionary of Global Transportation

Thomas Fletcher Waghorn (1800 - 1850) was during his day a very famous and controversial figure. To some, he was a charismatic visionary, years ahead of his time. To others, he was a self-aggrandizing confidence man – the truth perhaps is that he was both these things!

A native of Snodland, Kent, Waghorn joined the Royal Navy at the age of 12 and sailed the world, with particular experience in the East Indies. He became obsessed with shortening the monstrously long and unpleasant route from England to India that went via the Cape of Good Hope. As early as 1829-30, he claimed to have investigated a route from England to India the traversed Egypt’s Suez Isthmus, so reducing the travel distance by 5,000 miles, and the time from four months to 35-45 days. In 1832, Waghorn resigned from the navy, with the rank of Lieutenant, and dedicated himself to opening an England-Egypt-India route for commercial purposes.

Waghorn made several trips from England to India via Egypt, and even lived with the Arab tribes around Suez for two years in order to gain knowledge and local ‘street cred’. He also struck up a good relationship with Ibrahim Pasha, the ruler of Egypt, who supported of his plans.

In 1837, Waghorn founded a firm that transported mail and a limited number of passengers across the Suez, connecting them to steamship lines on both sides, so creating a fast connection between England and India. He also benefitted from being appointed Britain’s Deputy Consul in Egypt (albeit a post he held only for a short time, as he quarreled with his superiors).

For a time Waghorn’s enterprise appeared to be quite successful, as his route was considered the ‘gold standard’ for the fast transport of the post and important government communications between India and the home country. However, his business suffered when from 1840 the shipping behemoth P&O set up a rival service over the Suez, and it was taken out entirely in 1844 when 300 of his horses died of a plague. Waghorn then promptly sold what remained of his Egyptian assets and privileges to Ibrahim Pasha.

However, the failure of Waghorn’s Egyptian enterprise did little to dampen his enthusiasm for global transport and communications. He noticed that while the England-Suez-India connection was being well served, the onward trip to Australia was not well developed. Hitherto, most voyages from England to Australia travelled via the Cape of Good Hope and across the southern Indian Ocean, a brutal trip that usually lasted four months. Waghorn had a vision to halve the travel time, and made many proposals to the Crown to convince them to subsidize a steamship line from Singapore to Sydney. While these proposals gained a tremendous amount of attention in both London and in Australia, Waghorn failed to

secure the notoriously parsimonious government’s support.

As a consolation prize, the Crown agreed to pay for Waghorn to investigate an improved overland route across Europe (from Calais to Trieste), connecting to the Suez, so knocking time off the England-India run. Waghorn duly invested in several trans-European trials. Sadly, though, the government apparently did not follow through on the promised funds, leaving Waghorn £5,000 in debt – a large sum for the time.

Stressed by his constant travels and financial issues, Thomas Waghorn died suddenly in London at the age of 49.

However, Waghorn had a legacy that far outlived him. Dueling historians have debated whether Waghorn was a serious entrepreneur with credible, if not visionary, business plans for revolutionizing global travel, or, conversely, that he was huckster who knowingly exaggerated the viability of his schemes to bilk both the Crown and private investors. In any event, Waghorn was incredibly influential, for he drove the conversation that ultimately led to dramatic material improvements in travel between England, India and Down Under in the years after his death. Ferdinand de Lesseps, the man who completed the Suez Canal 1869, revered Waghorn, even erecting a statue to him in Egypt bearing the line “he opened the route, and we followed him”.

Thomas Ham (1821 -1870)

Thomas Ham: The Father of Map Publishing in Victoria Australia

Thomas Ham (1821 -1870) was the father of map publishing in Victoria, printing maps in Melbourne well in advance of the Gold Rush. Ham was a native of Devon, England, and immigrated to Melbourne in 1842, arriving with his parents and two brothers. His father soon became an important figure in town as the minister of the Collins Street Baptist Church.

Thomas had apprenticed as an engraver and lithographer in England and showed great natural aptitude for his profession. He benefited greatly from the fact that, during the early 1840s, he was one of the only people in Melbourne with any experience in printing, and so in 1843 he was contracted to engrave the corporation seal for the Town of Melbourne. He soon incorporated a business on Collins Street and became the official government printer in Melbourne, as well as fulfilling commissions from various banks, businesses and periodicals, such as the Port Phillip Herald. Additionally, philatelists value Ham’s work, for he engraved the first Victoria stamps.

Thomas and his brothers showed a great and skilled interest in land speculation and as early as 1845 they held titles to properties in the countryside beyond Melbourne. His contacts in government and in the settler community gave him unrivalled access to the latest geographic intelligence in the region. He realized the urgent need for an accurate and fully up-to-date map of the ‘Port Phillip District’ (later Victoria) and issued a Map of Australia Felix (1847), which was importantly the first locally produced map of the region.

Not unlike the situation in San Francisco, the discovery of gold in Victoria in 1851 led to a a mass influx of people, wealth and talent that fostered a thriving local print industry, as well as a unique and rich visual culture. From 1856, several other mapmakers were established on the Melbourne scene in effort to satiate the cartographic needs of prospectors and land speculators.

Ham’s Squatter’s Map of Victoria, the successor to his Australia Felix, became the seminal map of Victoria of the Gold Rush era. Published in eleven regularly updated editions up to 1864, it was the map of record used by all government officials, settlers, miners and land speculators, who frequently sent suggestions for additions and updates to Ham’s office, which were duly incorporated into subsequent issues.

Ham also issued other maps more focused on Melbourne and its environs, including Melbourne and Geelong Districts (1849), Map of the Suburban Lands of the City of Melbourne (1852) and Plan of the City of Melbourne (1854).

From 1850 to 1852, Thomas, with his brothers, Theophilus and Jabez, also published the Illustrated Australian Magazine, the first illustrated Australian periodical. Thomas also issued important views of the Gold Rush, including Ham’s Five Views of the Gold Fields of Mount Alexander and Ballarat, drawn by D. Tulloch (1852) and the plates within The Diggers Portfolio and The Gold Diggers Portfolio (1854).

In 1853, Ham and his brothers opened a successful real estate firm that became known as C., J. & T. Ham. In 1857, seeking to capitalize on the specific needs of the mining industry, he joined Victorian Geological Survey Office, where he made pioneering geological maps of the region.

In 1860, Ham moved the Brisbane where he became the lithographer and later the Chief Engraver of the Queensland Survey Office. The highlight of his tenure there was his Atlas of the Colony of Queensland (1868). Ham and some business partners also developed sugar plantations on the Albert River. Thomas Ham died at Brisbane on March 8, 1870, highly regarded for his work as a mapmaker and printer and wealthy from his land dealings.