Leen Helmink Antique Maps & Atlases

www.helmink.com

Joan Blaeu

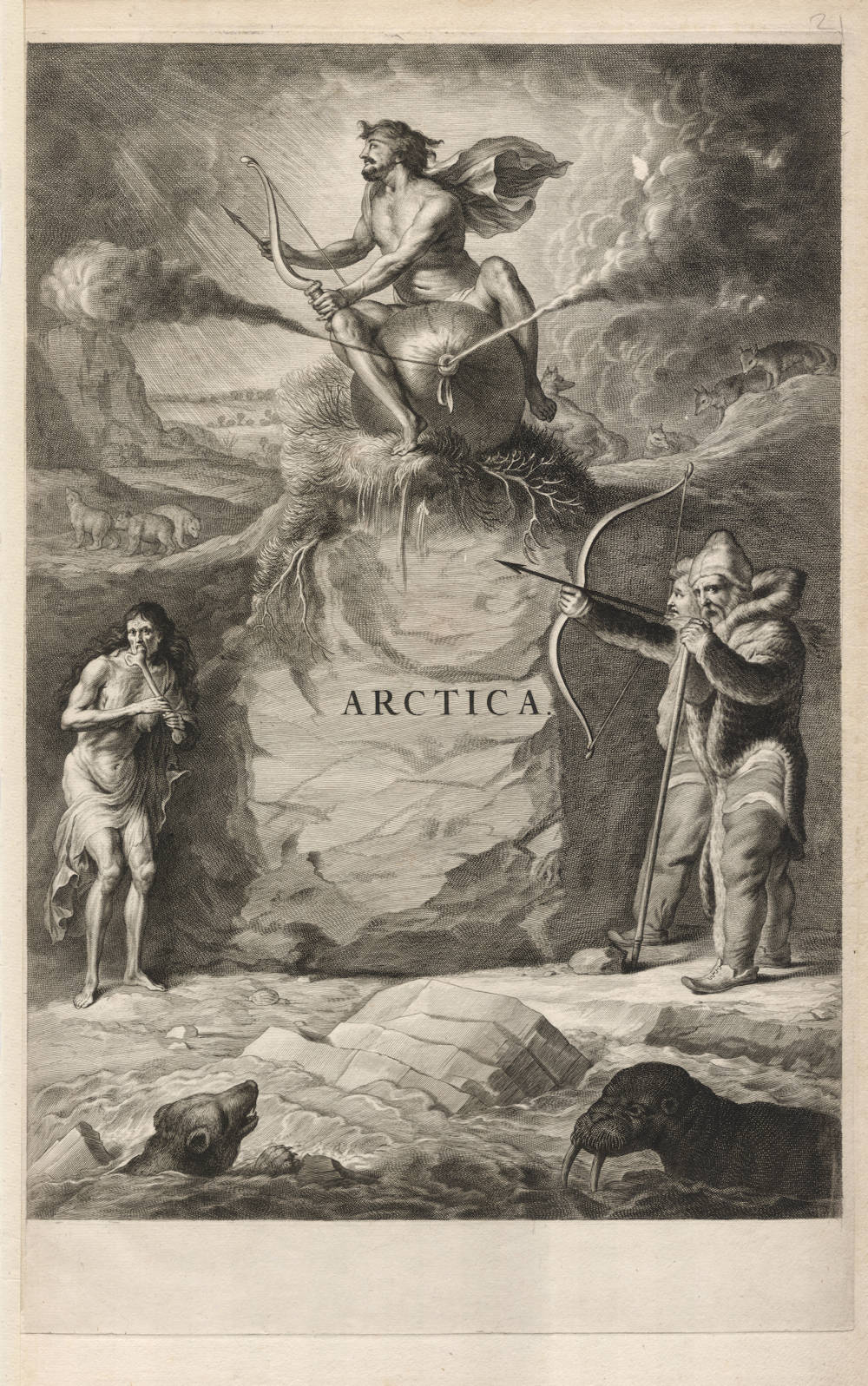

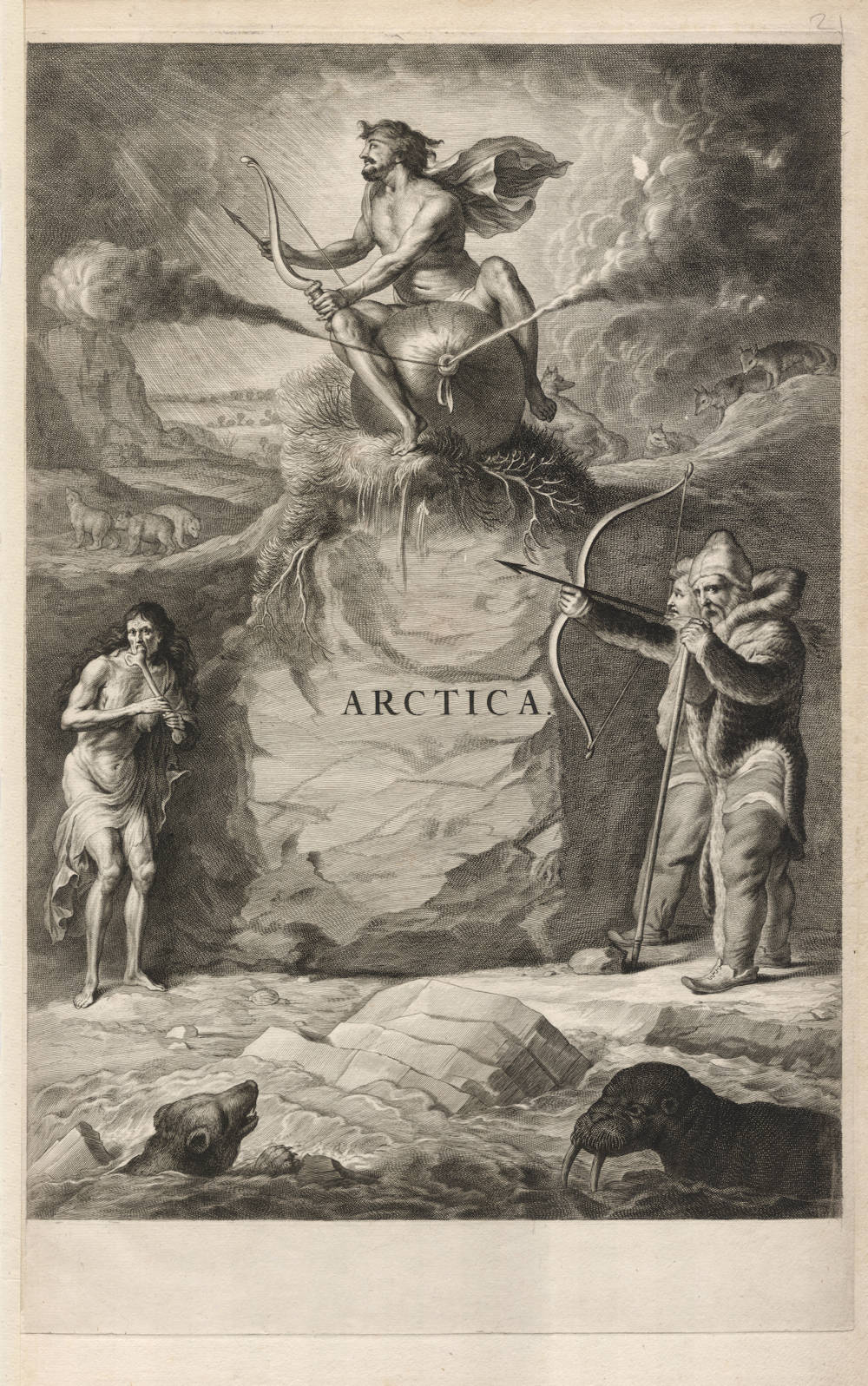

ARCTICA

Certificate of Authentication and Description

This is to certify that the item illustrated and described below is a genuine antique

map, print or book that was first produced and published in 1662, today 364 years ago.

March 3, 2026

Cartographer(s)

Joan Blaeu

First Published

Amsterdam, 1662

This edition

First edition (1662 Latin)

Size

47 x 30 cms

Technique

Copper engraving

Stock number

19157

Condition

mint

Description

Magnificent Atlas Maior allegorical frontispiece of the "continent" of Arctica. Lacking in all collections.

The iconology of the scene refers to a famous story in Homer's Odyssey. It depicts Odysseus with his bow and arrow sitting on a leather winebag containing the bad winds. Aeolus, the god of the winds and king of the mythical island of Aeolia, gave Odysseus a favourable gentle west wind together with a leather winebag in which the unfavourable and bad winds were confined, to bring him and his crew home safely, with the explicit warning not to open the bag under any circumstances. As usual, Odysseus gets in trouble later in the story. When almost home, Odysseus' men, thinking the bag contained treasure, opened it and they were all driven back to Aeolia by the bad winds. Believing that Odysseus must evidently be hated by the gods, Aeolus sent him away without further help. In this context the winds refer to the freezing cold polar winds.

The rock on which Odysseus sits presumably refers to the magnetic black rock or island that forms the magnetic pole. The theory was first introduced in Inventio Fortunata, a famous and unfortunately now lost book dating from the 14th century, describing several journeys to the Arctic. The book would have an immense influence to the early cartography of the Arctic.

The skinny nude lady gnawing on a thigh bone is an allegory for cannibalism. Two northern hunters are depicted, dressed in furs, with one of them looking at the viewer. A polar bear and a walrus are swimming in the front, surrounded by chipped ice. In the distance behind Odysseus we see a group of polar bears and a pack of Arctic wolves.

The overall storm and rain appearance resembles contemporary works by Peter Paul Rubens or Abraham van Diepenbeek. But because of the somewhat clunky composition compared to the Blaeu frontispieces of the other continents, that are designed by Nicholaes Berchem, it is likely that Blaeu's designer for this work has compiled something from different sources. The walrus is similar to Hessel Gerritsz' old copper engraving of the animal that is also in Volume I of the Atlas Major.

Interestingly, Rijksmuseum owns an unfinished proof state of this print which lacks the title, from the illustrious collection Frits Lugt, arguably the most famous and best collection of Dutch drawings and prints of all time.

Condition

Thick paper, with no paper discolouration or restorations. Early dark and even impression of the copperplate. First 1662 edition. Pristine example of an unobtainable item.

Courtiers and Cannibals, Angels and Amazons

The Art of the Decorative Titlepage

Joan Blaeu was the son and successor of the great globe, instrument, and atlas-maker Willem Janszoon Blaeu. After the death of his father in 1638 Joan expanded the family firm's atlas production considerably.

The culmination of their output was the publication of the Atlas Maior (or Grand Atlas) in 1662. In its most complete form the work comprises 11 or 12 parts or volumes and over 600 maps. Earlier atlases from the Blaeu establishment had titlepages centred around an architectural frame. However, for his Grand Atlas, Joan Blaeu broke away from this somewhat formal tradition and introduced a more pictorial composition as a general frontispiece, coupled with a typographic titlepage. There were five further frontispieces for the continental sections: Europe, Africa, America, Asia and Arctica.

Examples of Blaeu's main frontispiece were used for all impressions of his Atlas Maior throughout the 1660s. The continental frontispieces, however, are not found in all editions and thus in some cases they are quite rare.

(Rodney Shirley).

New Koeman Atlantes Neerlandici

Blaeu's title pages are symbolic or allegoric in form, depicting images either derived from classical antecedents or based in an allusive way on the atlas contents.

Joan Blaeu had designed and engraved for his Atlas Maior a series of five allegorical title pages: a general one for the atlas as a whole, and four for the continents Arctic, Europe, Africa, and America. For Asia a different title page was used, based on the title page of the Atlas Sinensis.

The design for these plates was probably by Nicolaes van Berchem (1620-1683) and they were engraved by Cornelis van Dalen, Jeremias Falck, and Johannes Visscher.

Except for the general title page, those prints were not used for all atlases.

(Peter van der Krogt).

Frontispiece Arctica for the Atlas Maior

Allegorical representation of Arctica. A god (Aeolus?) sitting on a bag from whichwind and clouds escape, on top of a rock, inscribed ARCTICA. The rock may represent the magnetic mountain that forms the northern magnetic pole. At both sides of the rock stands inhabitants of the northern lands. Furthern northern animals are depicted (ice bears, wolves and a walrus).

Occurrences: Very few copies of 1662ff Latin and 1664ff Dutch editions of Atlas Maior.

(Peter van der Krogt).

Aeolus In The Odyssey: Island of Aeolus

After escaping the island of Sicily, Odysseus’s men were caught in the middle of a storm, they were then led to an island seemingly floating above the waters. They climbed atop the land, looking for safety, and meet the king of the floating isle, Aeolus. He offered them shelter and the Greek men stayed for a few days.

They learned that the island was solely inhabited by the king, his wife, his six sons, and daughters. They eat and replenish their energy, sharing stories of their travels as Aeolus listens.

Aeolus and Odysseus bid each other goodbye, and the god of wind in The Odyssey gifts a bag filled with strong winds to Odysseus as a token of good faith but warns him not to open it. Aeolus then casts a favorable west wind to blow Odysseus’ ship towards his home in their journey.

Odysseus and his men sailed the seas for eight straight days with no rest or sleep, only resting once Odysseus had caught sight of their homeland. But as he was asleep, his men opened the bag of winds thinking that Aeolus gifted him gold; needless to say, that they caused all of the strong winds to escape.

The winds drove them off course for several days, leading them back to the island of Aeolia. They asked Aeolus to help Odysseus once again but were turned away as they were cursed by some other gods.

Upon leaving the Island, Aeolus found out that Odysseus had seduced one of his daughters and wanted to punish him. Along with Poseidon, the sea god, he sent the Ithacan men strong winds and storms that hindered their journey and lead to dangerous islands such as the island of the Laestrygonians, the man-eating giants.

(ancient-literature.com)

Willem Janszoon Blaeu (1571-1638)

Joan Blaeu (son) (1596-1673)

Cornelis Blaeu (son) (?-c.1642)

Willem Janszoon Blaeu died in October 1638, leaving his prospering business to his sons, Joan and Cornelis, who continued and expanded their father's ambitious plans.

After the premature death of his brother Cornelis in 1642, Joan directed the work alone and the whole atlas series of 6 volumes was eventually completed about 1655. As soon as it was finished he began the preparation of the even larger work, the Atlas Maior, which reached publication in 1662 in 11 volumes (later editions in 9-12 volumes) and contained nearly 600 double-page maps and 3,000 pages of text. This was, and indeed remains, the most magnificent work of its kind ever produced; perhaps its geographical content was not as up-to-date or as accurate as its author could have wished, but any deficiencies in that direction were more than compensated for by the fine engraving and colouring, the elaborate cartouches and pictorial and heraldic detail and especially the splendid calligraphy.

In 1672 a disastrous fire destroyed Blaeu's printing house in the Gravenstraat and a year afterwards Joan Blaeu died. The firm's surviving stocks of plates and maps were gradually dispersed, some of the plates being bought by F. de Wit and Schenk and Valck, before final closure in about 1695.

(Moreland and Bannister)