Leen Helmink Antique Maps & Atlases

www.helmink.com

Blaeu

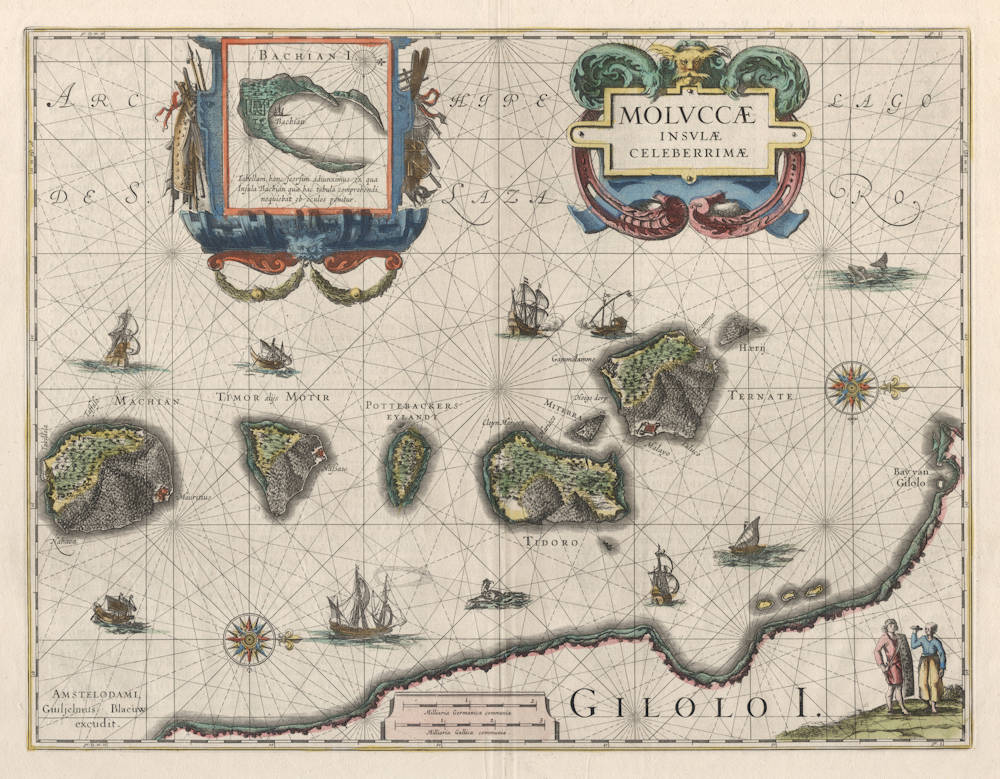

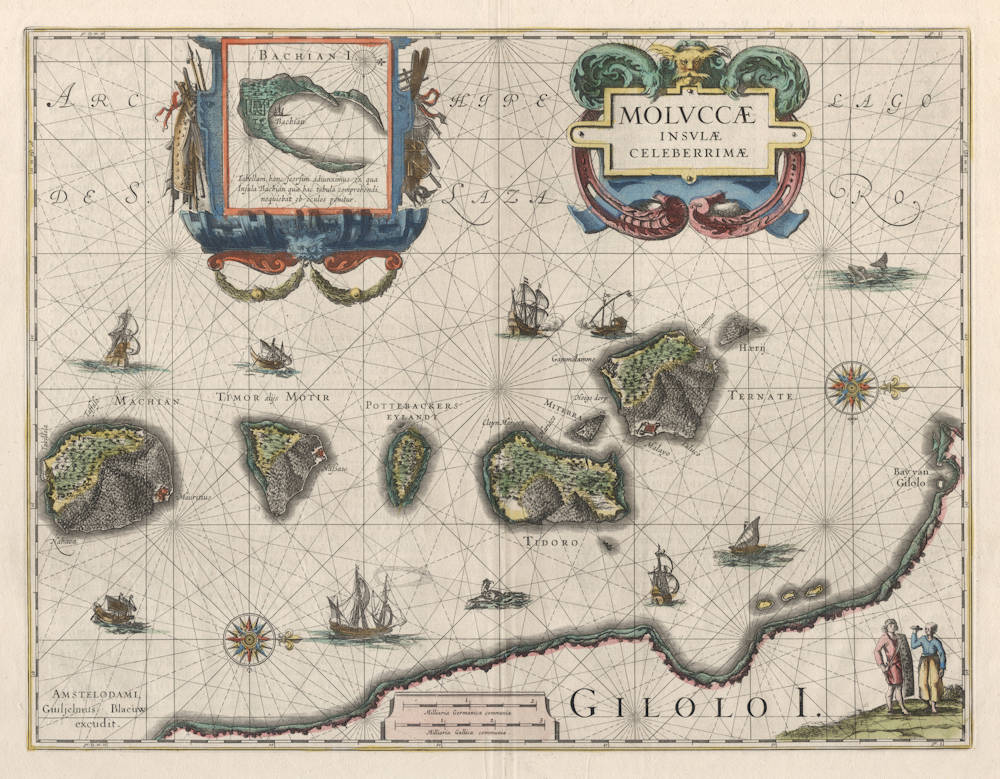

MOLVCCAE insulae celeberrimae

Certificate of Authentication and Description

This is to certify that the item illustrated and described below is a genuine antique

map, print or book that was first produced and published in 1629, today 397 years ago.

March 5, 2026

Cartographer(s)

Blaeu

First Published

Amsterdam, 1629

This edition

1647-48 Dutch edition

Size

37.0 x 48.5 cms

Technique

Copper engraving

Stock number

19097

Condition

mint

Description

One of the earliest and most decorative maps of the illustrious Spice Islands. One of the most appealing of all Blaeu maps. North is at the right of the map, meaning that it is oriented to the west.

Condition

This example from the 1647-48 edition, with Dutch text on verso. A dark and even impression of the copperplate. Strong and thick white paper. Very wide margins. A pristine example in stunning contemporary colour, from the time of publication, applied by the in-house colouring department of the Blaeu publishing company. Mint collector's condition.

A spectacular map of the spice islands, the ultimate prize of the European exploration of the East.

Heavily decorated with sea monsters and warships, the map shows an array of island fortresses and many fully-armed war-ships with gun-smoke, leaving competitors no room to doubt Dutch supremacy in the area.

According to an anonymous contemporary writer "No lover ever guarded his beloved more jealously than did the Dutch the islands where the clove trees grow."

The map is printed from one of the beautiful copper plates that Willem Blaeu acquired as early as as 1629 from the heritage of Jodocus Hondius the Younger, and that made it possible for Blaeu to publish his own atlas.

Blaeu's - The Grand Atlas of the 17th Century World

Willem Blaeu's map shows the Spice Islands of the East Indian archipelago, islands described by one sixteenth-century voyager, Jan Huyghen van Linschoten, as possessing cloves in so great abindance, that as it appeareth, by them the whole world is filled therewith ....

Ever since the first Portuguese expedition under Albuquerque from Malacca in 1511, the Spice Islands, or Moluccas, had been the great prize to Europeans in the East. Great attention was therefore paid by navigators and mapmakers to the accurate depiction of the islands and routes to them, both from Europe as well as from other European strongholds in the East. The early Portuguese navigators soon found that the most important of the Spice Islands were Ternate, Tidore (Tidoro on Willem Blaeu's map), and Halmahera (part of which is shown along the bottom of this map by a rendering of its native name as Gilolo) for cloves, and Amboina and the Banda Islands for nutmeg and mace.

From north to south respectively, the little islands shown on this map - the earliest large scale atlas map of the region - are known today as Ternate, Tidore, Mot and Makian and lie off the middle west coast of Halmahera in the northern part of the East Indies archipelago.

(Goss).

Willem Janszoon Blaeu (1571-1638)

Joan Blaeu (son) (1596-1673)

Cornelis Blaeu (son) (?-c.1642)

Willem Jansz. [Blaeu] and his son Joan are the most widely known cartographic publishers of the seventeenth century. Born as the son of a wealthy herring merchant in Alkmaar North Holland, to Anna, a first cousin of Willem. Cornelis Hooft was merchant in oil, grain and herring and twelve times mayor of Amsterdam. He hoped that Willem would take over his business.

But Willem was more interested in mathematics, astronomy and other scientific matters, however, and in 1595 he left for Denmark to study with the astronomer Tycho Brahe on the island of Ven. Brahe had established here his own observatory as well as a workshop for the manufacturing of instruments and a printing office. This enabled young Willem to acquire both theoretical and practical knowledge and provided him with contacts among like-minded people. After his return to the Netherlands he applied himself to astronomy for several years in his native Alkmaar. Here he published his first cartographic work: a celestial globe according to the observations of Tycho Brahe.

At the end of the sixteenth century Willem Jansz. moved with his family to Amsterdam. He set up a shop in celestial and terrestrial globes and nautical instruments, since the rapid growth of seafaring opened a large market for these goods. Soon he was able to offer for sale globes in various sizes. In 1605 Willem Jansz. moved to a new location at the "Op ‘t Water" (today Damrak nr. 46), a house with the sign of in de Vergulde Sonnewijwyser ("in the Gilded Sundial"). Apart from the manufacturing globes, Willem Jansz. published numerous maps and charts in folio size, along with multi-sheet wall maps, town views, and historical prints, all of which are now very rare.

Willem Jansz. made an unmatched contribution to the fields of navigation and cartography. His "Het Licht der Zee-vaert", published in 1608, was of great consequence for navigation in European coastal waters. He used the same oblong-size like Waghenaer did in his "Thresoor der Zeevaert" (1592): the work was constructed in a series of chapters, adding to each chapter sailing-descriptions for a specific stretch of coast and the corresponding chart. The coastal profiles in woodcut have been included in the text of each chapter.

In 1618 another mapmaker, bookseller and publisher, Jan Jansz. (Joannes Janssonius) established himself on the Damrak next door to Willem Jansz.’s shop. Accusing each other of copying and stealing information, the neighbours became fierce competitors. In about 1621, Willem Jansz. decided to put an end to the confusion between his name and his competitor’s and assumed his grandfather’s sobriquet, (Blauwe Willem), as the family name; thereafter he called himself Willem Jansz. Blaeu.

Responding to Janssonius’s plagiarism of "Het Licht der Zeevaert", Blaeu published a new pilot-guide in 1623: the "Zeespiegel", a description of the seas and coasts of the Eastern, Northern and Western Navigation. Approximately the same coastal areas are described as in the older "Het Licht der Zeevaert", but in a much more elaborate way and with a far greater number of charts.

Apart from pilot-guides, Blaeu also published single-sheet charts, often printed on durable vellum. As example attention is here given to the so-called "West-Indische Paskaert", a chart of the Atlantic Ocean in Mercator’s projection, published about 1630. Despite the obvious advantages for navigation, the charts drawn on this projection were only gradually accepted by navigators.

Blaeu was nearing the age of sixty when in 1630 he published his first atlas of the world and began to compete with Henricus Hondius. For many years Blaeu toyed with the idea of publishing his own atlas of the world. The initial material for an atlas was in Blaeu’s hands in the form of his own folio-maps, which he had begun publishing in 1604. Blaeu’s plan gained momentum, however, when he succeeded in 1629 in purchasing a large number of copperplates that had belonged to the late Jodocus Hondius the younger. Blaeu quickly amended these plates by replacing Hondius’s name with his own imprint, a common procedure in those days. In 1630 Blaeu published the "Atlantis Appendix", using his own maps and the amended maps of Jodocus Hondius. The world atlas consists of 60 maps, but without a descriptive text. In 1631 a new world atlas was published , titled "Appendix Theatri A. Ortelii et Atlantis G. Mercatoris", provided with a Latin text and nearly hundred maps. The intention in publishing this atlas was to produce a supplement to the works of the two famous geographers. Henricus Hondius and his brother-in-law Joannes Janssonius immediately took steps in reaction to the publication of Blaeu’s "Appendix" and published amended atlas-publications.

The fierce competition between Blaeu and Hondius-Janssonius greatly influenced the further development of their atlas productions. Blaeu now intended to distance himself completely from Ortelius and Mercator and to publish an entirely new world atlas in four languages. In 1634 a German edition was published, which contains a number of unfinished maps, a sign that the work was done hurriedly in order to have the atlas published in time.

The extent of Blaeu’s ambitious plans for the world atlas is reflected in his preface, where he states that it is his intention to describe the whole world and to depict all the ports and seas, and therefore several other volumes of the atlas were to follow shortly. In view of these plans, Blaeu’s investment in a new printing shop in 1637 is not surprising. Yet Blaeu did not live to see the publication of a new volume. After his death the business was continued by his two sons Joan and Cornelis, the elder of whom had been collaborating on the atlas since 1631. In 1640 a third volume was published (Italy), in 1645 a fourth (England and Wales), in 1654 a fifth (Scotland) and finally in 1655, a sixth volume covered China.

In addition to his activities as publisher, Willem Jansz. Blaeu continued his scientific pursuits. His expertise won official recognition at his appointment as chart maker and examiner of navigating officers by the Amsterdam Chamber of the United Dutch East India Company (VOC).

Blaeu’s new position gave him access to the enormous map archives of the VOC. He performed the function of chart maker until his death in 1638. For his task he employed the four assistants of his deceased predecessor Hessel Gerritsz. Blaeus’s work was most probably limited – given his age – to the supervision of his employees in the manufacture of charts, to the supervision of content and to any alterations and improvements required. A steady stream of charts, required to equip the ships, must have left his workshop. Thanks to his position as chart maker of the VOC, Blaeu was able to expand his world atlas of Asia with new maps and gain the edge on his Amsterdam competitors, Hondius and Janssonius.

Willem Jansz. Blaeu died in October 1638, leaving his prospering business to his sons, Joan and Cornelis.

(Schilder)

Jodocus Hondius (1563-1612)

Jodocus Hondius II (son) (1594-1629)

Henricus Hondius (son) (1597-1651)

Jodocus Hondius the Elder, one of the most notable engravers of his time, is known for his work in association with many of the cartographers and publishers prominent at the end of the sixteenth and the beginning of the seventeenth century.

A native of Flanders, he grew up in Ghent, apprenticed as an instrument and globe maker and map engraver. In 1584, to escape the religious troubles sweeping the Low Countries at that time, he fled to London where he spent some years before finally settling in Amsterdam about 1593. In the London period he came into contact with the leading scientists and geographers of the day and engraved maps in The Mariner's Mirrour, the English edition of Waghenaer's Sea Atlas, as well as others with Pieter van den Keere, his brother-in-law. No doubt his temporary exile in London stood him in good stead, earning him an international reputation, for it could have been no accident that Speed chose Hondius to engrave the plates for the maps in The Theatre of the Empire of Great Britaine in the years between 1605 and 1610.

In 1604 Hondius bought the plates of Mercator's Atlas which, in spite of its excellence, had not competed successfully with the continuing demand for the Ortelius Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. To meet this competition Hondius added about 40 maps to Mercator's original number and from 1606 published enlarged editions in many languages, still under Mercator's name but with his own name as publisher. These atlases have become known as the Mercator/ Hondius series. The following year the maps were re-engraved in miniature form and issued as a pocket Atlas Minor.

After the death of Jodocus Hondius the Elder in 1612, work on the two atlases, folio and miniature, was carried on by his widow and sons, Jodocus II and Henricus, and eventually in conjunction with Jan Jansson in Amsterdam. In all, from 1606 onwards, nearly 50 editions with increasing numbers of maps with texts in the main European languages were printed.

(Moreland and Bannister)